A report out of the Local Government Ombudsman on the complaints it receives about adult social care suggests a system that is under considerable stress. Social care complaints have increased significantly and are predicted to continue rising while at the same time spending by local authorities on social care fell in real terms and is predicted to continue falling. The report suggests a future vision for the social care complaints system. Jane Tinkler argues that a joined-up and systematic oversight of the system needs to be instituted.

A report out of the Local Government Ombudsman on the complaints it receives about adult social care suggests a system that is under considerable stress. Social care complaints have increased significantly and are predicted to continue rising while at the same time spending by local authorities on social care fell in real terms and is predicted to continue falling. The report suggests a future vision for the social care complaints system. Jane Tinkler argues that a joined-up and systematic oversight of the system needs to be instituted.

Last week the Local Government Ombudsman (LGO) published its first report looking at the complaints it receives about adult social care. Social care is obviously a complex area but it is also an expensive one; a recent NAO report found that £19 billion is spent on adult social care by local authorities per year. In addition, there is also an estimated £10 billion spent on self-funded care and support. So the information provided by complaints on how services are working and can be improved is vital both for the quality of the lives of vulnerable people but also so that this significant resource is being well spent.

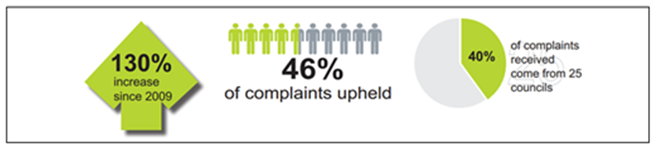

One noteworthy finding from the report is that the LGO has seen a 130 per cent increase in social care complaints since 2009. Some commentators have already outlined how this might be a good thing. And it’s true that this increase could be an indication that complaints processes are more accessible or that people are increasingly confident of using them and trusting that something might change as a result. But it could just as easily be a negative sign of how service quality is holding up, or more accurately not holding up, to budget cuts at a time of increased demands on social care services. Local authority social care total spending fell by 8 per cent in real terms between 2010-11 and 2012-13 and is predicted to continue falling.

That’s the trouble about complaints figures; they can be read a number of ways. It is therefore important to really understand the system: a significant problem when the public sector complaints system is as labyrinthine as it is and systematic oversight is lacking. It’s a key reason why I’ve written on this blog in the past about the need for a joined-up public services ombudsman.

And the benefits of consistent oversight can be seen in this report, albeit just in one policy area. The LGO has always been responsible for council run and funded social care services but since 2009 it has also been able to look at private sector and commissioned services. So its ability to look at “any registered care service, whoever is using it and however it has been arranged or funded” gives the LGO the chance to systematically see how social care services are working.

The 2,456 complaints that it received about social care represented the fastest growing area of its remit, thereby suggesting a system that is under considerable stress. In one way an increase in complaints might be expected as the demands for care services are also growing. Those with complex and long term conditions are living longer and so they need care over longer periods. There is variation in terms of level of need in local areas and therefore how much each local authority is spending.

The pressure on some areas in particular can be seen by 40 per cent of complaints coming from just 25 local councils. The report maps the areas of higher complaints onto areas where dissatisfaction with social care services have been found to be higher (via the Personal Social Services Adult Social Care Survey) and find no direct correlation. The distribution also doesn’t seem to map onto areas where there is a higher percentage of self-funded care. (This might have been relevant as our previous research found that local authority complaints seem to increase in areas where they have higher council tax.) So a higher level of dissatisfaction in an area is not necessarily translating into an increased number of complaints.

Aside from the significant growth in complaints going to the LGO, the other finding that stands out is that 46 per cent of the complaints that the LGO investigates are upheld (i.e. they find in the complainants favour). For some categories of complaint the rate upheld is over half. This doesn’t seem to indicate a redress system that is working well. Bearing in mind that to be eligible for investigation by the LGO, your case will have already gone through a full complaints process within the local authority or private provider, possibly through two tiers within each organisation. So these complaints are long-standing and the complainants will have been waiting a long time for a decision.

The LGO’s complaints are still predominantly (86 per cent) about public sector care. Private sector complaints only make up about 9 per cent of the LGO’s workload, and this percentage has not increased over recent years. Only 3 per cent of complaints were able commissioned care. But this doesn’t necessarily mean that private sector or commissioned care is significantly better. Rather it may be that service users are unsure how to make complaints about these services. There are indications of this as the LGO found that more complaints, about a quarter, about commissioned services had not been through an earlier complaints process and were coming to the LGO as their first resort. In addition, those complaining about commissioned services were more likely to have a decision upheld at 65 per cent in comparison with 41 per cent of complaints about local councils.

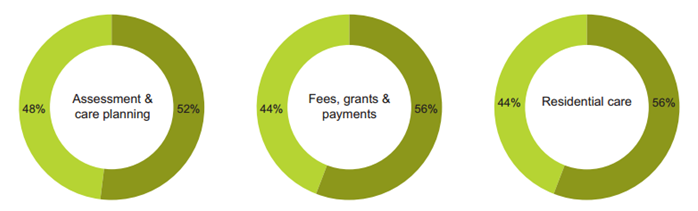

Turning to the categories of complaints, the three aspects of social care most complained about were assessment and planning of care, its funding via fees, grants and payments, and residential care. And as the figure below shows, in these three areas over half of the complaints were upheld (shown in the darker green). Firstly, around 18 per cent of complaints overall were about the assessment and planning of care. This is a legal duty for councils but the report identified many cases where processes were not being followed or being followed badly. Another 17 per cent of complaints were around the financial elements of social care services. More than half of these complaints concerned issues of fees being charged in circumstances where they should not. This was not just within local authorities but also private providers where ‘top-up’ fees were being incorrectly charged where costs were not being fully covered by local authorities. The largest increase in any one category was for complaints about residential care.

Complaints to public sector bodies often involve very difficult and complex situations. Those complaining are often friends or family of service users who are concerned about the vital care their friend or relative is receiving. But they are also anxious about making their situation more difficult as users are often unable to easily move to a different care provider if the relationship sours. And conversely the social care workforce is also relatively lowly paid and with lower job security than other public sector services. Recent estimates of 9 to 12% of direct care workers paid under the national minimum wage. The pressure on budgets and secure employment will surely be leading to a stressed and demoralised workforce, and it is difficult to know how well supported social care staff are in handling complaints at a time when they themselves feel under threat.

Complaints to public sector bodies often involve very difficult and complex situations. Those complaining are often friends or family of service users who are concerned about the vital care their friend or relative is receiving. But they are also anxious about making their situation more difficult as users are often unable to easily move to a different care provider if the relationship sours. And conversely the social care workforce is also relatively lowly paid and with lower job security than other public sector services. Recent estimates of 9 to 12% of direct care workers paid under the national minimum wage. The pressure on budgets and secure employment will surely be leading to a stressed and demoralised workforce, and it is difficult to know how well supported social care staff are in handling complaints at a time when they themselves feel under threat.

The LGO report ends with a ‘vision for the future of social care complaints’. The report rightly states that there has been a significant focus on health care complaints and streamlining that complex process. Many of the conclusions of the Francis and Clwyd-Hart reviews could equally well apply to the social care complaints system. The report calls for statutory signposting of the redress process, so the onus is on the provider to give information on how to complain rather than the user having to seek it out. They also recommend increased advocacy support so that those that need help to complaint have more access to it. They call for an annual report on complaints by providers that then feed into mandated data returns on complaints to CQC so that their oversight of local complaints handling can be strengthened.

These are clear and sensible recommendations for a social care system that stretched in terms of demand but also by being integrated with health services. How this is done is crucial to the effectiveness of an integrated system and there is “limited evidence for successful ways to integrate” and timeframes for planning are tight. The government is relying on new arrangements for monitoring of social care providers and these new arrangements are not yet at pilot stage. Redress arrangements must be an integral part of this planning and a joined-up and systematic oversight of the system needs to be instituted.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Homepage image credit: British Red Cross.

Jane Tinkler – LSE Public Policy Group

Jane Tinkler – LSE Public Policy Group

Jane Tinkler is Research Fellow at the LSE Public Policy Group. She also oversees the Public Policy Group’s six academic blogs: British Politics and Policy, European Politics and Policy, American Politics and Policy, Democratic Audit, the LSE Review of Books and Impact of Social Sciences blog. Her academic research interests focus on the quality of public services in the UK. Her most recent publication (with Bastow and Dunleavy) is ‘The Impact of the Social Sciences: How Academics and Their Research Make a Difference‘ (SAGE, 2014).