The rising cost of living is more than an economic squeeze: it is a public health emergency, potentially on a par with the COVID-19 pandemic. Not being able to afford the essentials, such as food, rent, heating or transport, has wide-ranging negative impacts on mental and physical health and well-being. Manon Roberts and Louisa Petchey discuss new research from Public Health Wales looking at the impact on people in Wales and exploring what a system-wide response that protects and improves health could look like.

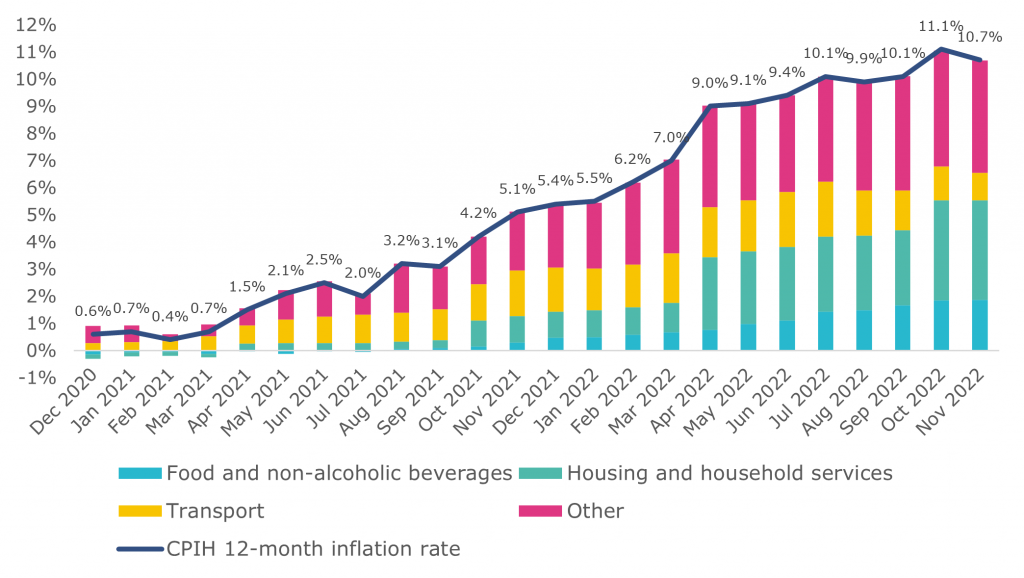

Having a warm, dry place to live, nutritious food, fair work and a sense of security are fundamental building blocks for a healthy life. Throughout 2022, we saw rapid rises in the cost of essentials – energy, housing, food and fuel (Figure 1) – that have outstripped average increases in people’s wages and welfare payments.

Figure 1. Annual consumer price inflation rate, UK, December 2020 to November 2022.

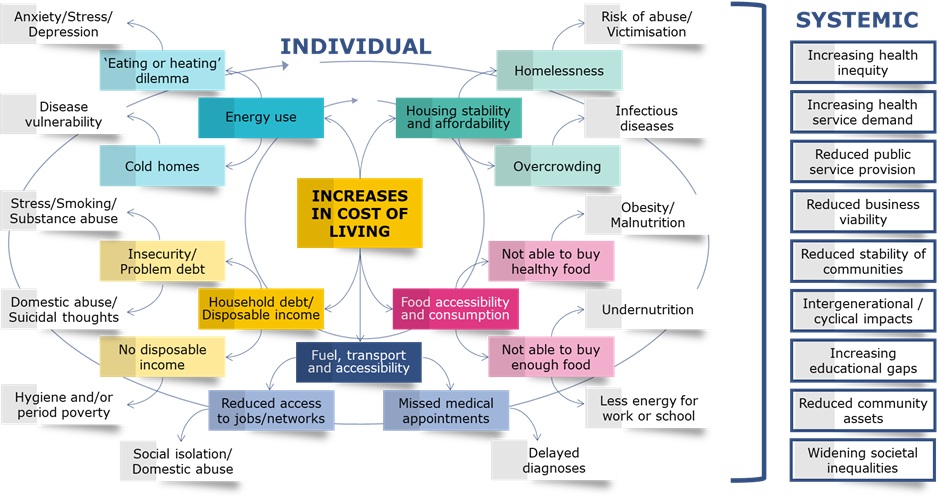

This has significant and wide-ranging negative consequences for mental and physical health and well-being (Figure 2).

For example, not having the money to put the heating on means living in cold and damp conditions. This increases the risk of heart attacks and stroke, as well as arthritic and respiratory conditions. Older people, children and babies are at particularly high risk.

Figure 2. Mapping the links between the cost-of-living crisis and health.

With food prices also high, many people are forced to choose between heating and eating, meaning households will face multiple challenges at the same time. As a result, many people are unable to adequately feed themselves or their families enough food, let alone nutritious, healthy food. A good diet is essential for good health in the short and longer term, with obesity a major risk factor for conditions such as diabetes and cancer. Making such difficult decisions on how to spend limited household budgets also takes its toll on mental health.

These health and well-being impacts are compounded by a system that is struggling to respond to growing need, with businesses, charities and public services also battling increased costs. This comes off the back of the pandemic, which put unprecedented demand on health and social care services.

While some of these problems will ease as costs fall, others may persist. For example, people who have gone into debt may still have debt even when inflation rates settle. Some people may have lost their homes or businesses. Others may still be affected by the poor health conditions they developed as a result of not being able to eat well, keep warm, stay connected to friends or attend medical appointments. They may not be able to look to a better future because fatigue and hunger stopped them from doing well at school. All these health and well-being impacts can extend throughout people’s lives and may transfer across generations.

Who will be most affected?

Like the COVID-19 pandemic, the negative impacts of the cost-of-living crisis on health and well-being are being disproportionately felt by those on the lowest incomes in Wales. This is likely to include lone parents, people living in more deprived areas, homeless people, people living with disabilities, older people and children. It also risks pushing more people in Wales from just about coping to a state of struggling or crisis, while those who were already the worst off will see their situation deteriorate further. This leads to a large-scale health crisis with severe consequences for some people and families.

People living in the poorest parts of Wales already die more than six years earlier than those in the least deprived areas, and experience more years of poorer health. Without appropriate action, the cost-of-living crisis will make this situation worse still.

What would a public health response look like?

In Public Health Wales’ report, we make the case that the cost-of-living crisis is a long-term public health issue and therefore requires an urgent public health response. The five core elements that characterise a public health approach are detailed in Figure 3 below.

The response should do two things: mitigate the negative effects of the immediate crisis across a number of policy areas and tackle the underlying causes of health inequalities to create a healthier and more equal Wales in the long-term.

Figure 3. Five elements common to public health approaches.

Immediate action is needed across a range of areas to mitigate health harms, focusing on those hardest hit. Measures must focus on higher fuel and food prices and stretched public service, particularly over the winter months. Examples include identifying and targeting support to those living in cold homes and supporting local initiatives that help people to stay warm and eat well.

The risk that the cost-of-living crisis poses to people’s mental health is an urgent concern, with poor mental health closely linked to poverty and low incomes. Mechanisms for maximising income, particularly for those with the lowest incomes, will improve mental and physical health by reducing financial strain and making essential goods more affordable.

Effective policies start with health and well-being

The cost-of-living crisis can and should also serve to mobilise action now in areas that will benefit population health and well-being in the medium to longer term.

A key example is investing in warm homes: evidence shows that every £1 spent on improving warmth in vulnerable households results in £4 of health benefits. Other examples include improving housing availability, affordability and quality to reduce the risks of living in unsafe properties or of homelessness. Making it easier for people to access screening and vaccination services with sustainable travel options has dual benefits for preventing future health issues and tackling climate change and its impacts on health. Promoting fair work with fair pay can help reduce the number of working people living in poverty or on precarious incomes.

The negative impacts of the cost-of-living crisis – and the COVID-19 pandemic before that – are so significant because they aggravate the existing vulnerabilities of poverty and inequality. Therefore, any public health response must also tackle these underlying causes so that health and well-being are improved for all.

This means putting health and well-being considerations at the heart of all policy-making that affects the building blocks for a healthy life, such as employment, education, the economy, housing, planning and the environment – with a particular focus on ensuring every child has the best start in life.

Wales has the legislative framework to achieve this through the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015, the Public Health (Wales) Act 2017 and the Socio-economic Duty. Together these require the Welsh Government and public sector to make decisions that prioritise well-being.

The current cost-of-living crisis can and must provide the catalyst to accelerate progress on making Wales a healthier and more equal place to live. Grasping this opportunity will not only improve population health and well-being but will also put us on a surer footing for the public health challenges that no doubt lie ahead.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by Hush Naidoo Jade Photography at Unsplash