Populist movements of both left and right have been one of the stories of recent years, with the likes of UKIP increasing in popularity. In an age of political platitudes and a marked disconnect between elected and electors, Claudia Chwalisz argues for the greater use of deliberative methods as a way of bringing the marginalised back into the fold.

Populist movements of both left and right have been one of the stories of recent years, with the likes of UKIP increasing in popularity. In an age of political platitudes and a marked disconnect between elected and electors, Claudia Chwalisz argues for the greater use of deliberative methods as a way of bringing the marginalised back into the fold.

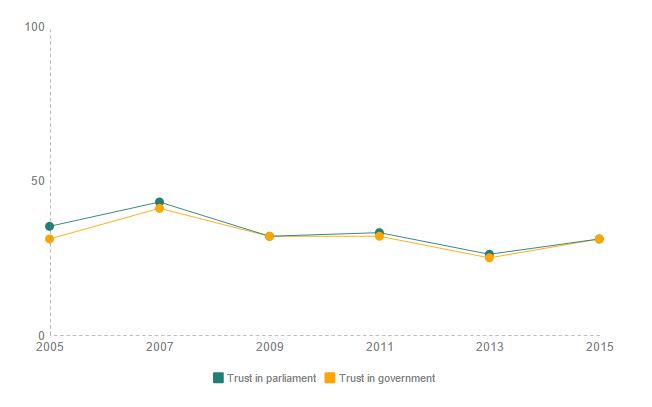

It has become fashionable to despair the death of democracy. Party membership is dwindling, voter turnout is falling, and people are apathetic and disengaged. Less than one third of those in the EU trust their parliament or their government (see Figure 1). The late political scientist Peter Mair called this ‘ruling the void’.

Yet, what is it that makes today’s situation remarkable? Looking at Figure 1, despite some marginal variation, the level of trust in national political institutions has remained relatively stable over the past 10 years.

Figure 1: Trust in national governments and parliaments in EU, 2005-2015

Source: Eurobarometer

A recent paper by Ann-Kristin Kölln in Party Politics looking at 47 parties in six western European countries between 1960 and 2010 shows that party membership decline is by far not a universal phenomenon. The older and more consolidated parties are, the fewer members they have. Christian and social democratic parties have been consistently losing members, while newer Green parties have been gaining.

Kölln’s research does not touch on populist parties either. Podemos in Spain, Syriza in Greece, and the Five Star Movement in Italy are just a few of the new parties to gain political movement over the past few years. In the UK, the Greens, the Scottish Nationalist Party and UKIP also drastically increased their membership figures over the course of the 2015 general election campaign.

The story about democratic decline is thus more complex. In my recent report The Populist Signal, new Ipsos Mori polling highlights that people are not in fact completely disengaged; rather, it appears that they are angry and disillusioned, but open to more active and deliberative forms of political participation.

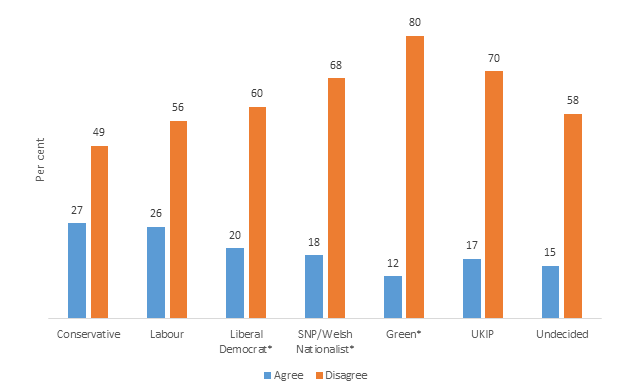

New polling by Ipsos MORI for the report highlights how only 31 per cent of people feel like their voice counts in the decisions taken by local politicians. A mere 21 per cent feel they are heard by national politicians. Voters of ‘outsider’ parties feel especially disenfranchised – only 18 per cent of SNP voters, 17 per cent of UKIP voters and 12 per cent of Green voters feel like their voices count in national political decision-making.

Figure 2: How strongly, if at all, do you agree with the following statements? I believe my voice counts in the decisions taken by national politicians

Note: * indicates smaller sample size

The polling also indicates that 68 per cent of voters feel the current system of governing Britain needs improvement. A feeling that is once again much stronger among ‘outsider’ party voters – 90 per cent of SNP, 77 per cent of Green and 83 per cent UKIP voters are unhappy with the status quo – compared to 41 per cent of Conservative voters. Large swathes of voters are left feeling that politics does not work; they are concerned with the process of politics, not merely its performance.

The report goes on to investigate the potential of democratic innovations – new institutions involving civic engagement, random selection and a genuine shift in policymaking power to people – to alleviate the deeply held scepticism and distrust of ‘the establishment.’ Here, the results offer some optimism in the midst of the current state of democratic gloom.

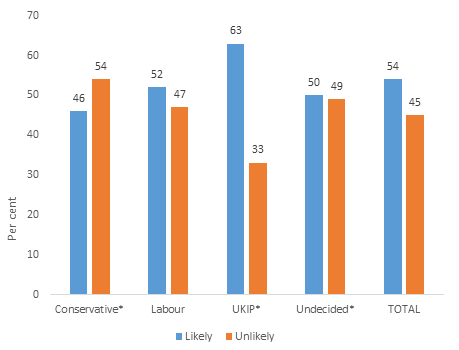

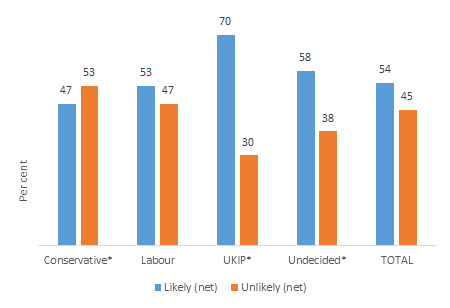

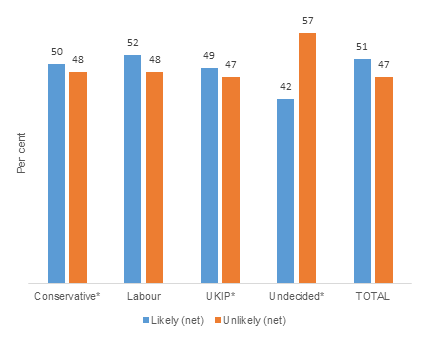

In contrast to the feelings of political alienation, the polling shows there is a clear desire for active, deliberative forms of political participation. 54 per cent of all respondents said they would participate in randomly selected citizens’ assemblies on local issues, regardless of whether the decisions were binding or not. Fifty per cent were willing to do so for a national-level assembly.

Figure 3: Willingness to participate in a local citizens’ assembly (with non-binding results) by political party

Note: * indicates smaller sample size

Figure 4: Willingness to participate in a local citizens’ assembly (with binding results) by political party

Note: * indicates smaller sample size

Over 50 per cent of respondents are willing to participate in a constitutional convention involving ordinary citizens, politicians and experts to develop proposals for how the UK should be governed. SNP and Green voters are especially enthusiastic, with 70 and 78 per cent willing to take part respectively. This would be a democratic alternative to the current devolution agenda, being handled in the traditional, top-down way of powers being handed down from the throne of Westminster.

Figure 5: Willingness to participate in a non-binding Constitutional Convention by political party

Note: * indicates smaller sample size

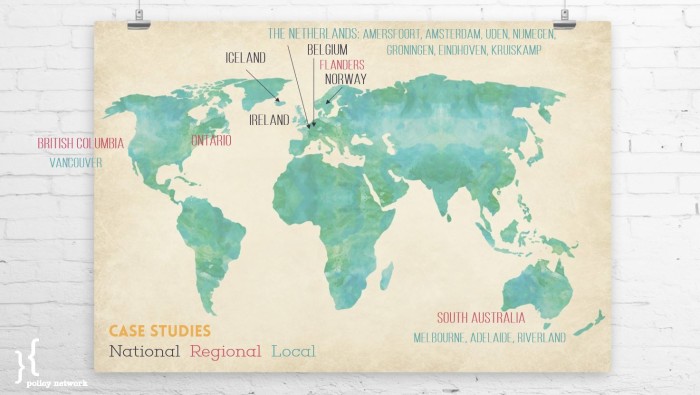

The evidence from international case studies is even more encouraging. Drawing on 10 examples, the report highlights some of the best practice when it comes to new ways of involving citizens in politics and in policymaking.

Figure 6: Map of international case studies detailed in The Populist Signal

For example, Canada has been quietly becoming a laboratory for deliberative democracy. Certain cities, municipalities and provinces have been advocating for more citizen involvement in public policymaking for about a decade. The recently completed Grandview Woodlands Citizens’ Assembly in Vancouver on town planning shows that there is scope for democratic innovation on a wide range of issues. For the first time ever, renters, young people, and minorities – groups typically excluded from the planning process which tends to be dominated by wealthy owners with time on their hands – made a significant contribution to shaping the future of their community for the next 30 years.

On the other side of the world, the pace of innovation has not slowed down in Australia since the report’s publication. South Australian premier Jay Weatherill launched a new raft of measures to increase citizen participation in public policy. Civic engagement is not just an afterthought, in his eyes it is “the single biggest issue confronting politics”. It is why the Australian state has been leading the way in democratic innovation for the past few years. Randomly selected citizens’ juries are being used to decide controversial policies – with immediate response and follow-up from the Premier and his government. One particularly inspiring example is the Melbourne People’s Panel, which recently presented the city’s council with a 10-year, $4 billion (AUD) financial plan. It was almost unanimously accepted.

Looking back to Europe, Belgium and the Netherlands have undoubtedly been the pioneers in the field. The Flemish Minister of Culture Sven Gatz has established a Citizens’ Cabinet to advise on his upcoming legislation in October. And in more than ten Dutch cities now, local G1000 citizens’ assemblies have been transforming local government into a collaborative effort between the elected and their communities.

To counter populists feeding off of a politics of grievance, there is a need for mainstream actors to consider these kinds of new initiatives and new institutions that give people a genuine voice in making the decisions that affect their lives.

The ancient Athenian practice of drawing participants by lot is arguably an important aspect of many of these innovations. While many people sign petitions and voice (or vent) their opinions online, to move people from being ‘armchair activists’ towards real, productive engagement in their communities requires an opportunity for real world engagement.

Furthermore, random selection counters the trend it tends to be the most highly educated and better off individuals who are most likely to be involved in all types of political activity – from voting, to protesting or campaigning. Making policy decisions through citizens’ assemblies or juries tries to mitigate this trend; participants are representative of the public in terms of age, gender, geographical spread, education level and socioeconomic status.

Of course these types of democratic innovations are not a short term or quick fix solution to restoring trust in democracy or alleviating political disaffection. Citizens’ assemblies or juries tend to involve a small number of people at a time, but if they happen on a recurring basis, and people learn to trust the process, there is definitely scope for reversing the declining trust in our political institutions and increase the legitimacy of decisions being made in our local and national communities.

It is the mindset associated with implementing these kinds of democratic innovations on a wider scale that is most badly needed. Weatherill describes it best as moving away from government that ‘announces and defends’ its policies, to one that ‘debates, designs and decides’ policies together with the input and wisdom of the people they will affect. It is a real devolution of power directly to communities and individuals themselves, not merely to newly created layers of political elites. While these new forms of citizen engagement may appear as a threat to formal systems of government, they are much-needed additions that enrich democracy.

Note: This article was originally published on the Democratic Audit blog. To see the full Populist Signal report click here.

Claudia Chwalisz is a senior policy researcher at Policy Network and a Crook public service fellow at the Crick Centre, University of Sheffield. She is the author of The Populist Signal: Why politics and democracy need to change (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015)

Claudia Chwalisz is a senior policy researcher at Policy Network and a Crook public service fellow at the Crick Centre, University of Sheffield. She is the author of The Populist Signal: Why politics and democracy need to change (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015)