The government’s Trade Union Bill proposes draconian new restrictions for labour unions, including higher thresholds for strike ballots and curbs on picketing. In this article, Bart Cammaerts argues that the right of workers to strike is fundamental, writing that it is Orwellian newspeak to claim that the Tories are the party of working people and at the same time curtail the rights of these same working people.

The government’s Trade Union Bill proposes draconian new restrictions for labour unions, including higher thresholds for strike ballots and curbs on picketing. In this article, Bart Cammaerts argues that the right of workers to strike is fundamental, writing that it is Orwellian newspeak to claim that the Tories are the party of working people and at the same time curtail the rights of these same working people.

The announcement of the current Tory-led government to make the anti-strike legislation in the UK even more stringent than it already is, is taking things even further away from what should be a right to strike.

The right of workers to strike is in many ways a fundamental democratic right. It is part of the broader civic right of association and this right is the outcome of a protracted struggle between the inherently conflictual interests of workers on the one hand and employers on the other or between labour and capital to put it in Marxist terms. The withdrawal of labour, the disruption of production and even acts of sabotage are longstanding weapons of the weak, which have always been considered in varying degrees as illegitimate weapons by the capitalist state and those that represent the dominant interests in society.

Despite this, industrial action as it is now called is a widespread and hugely successful protest tactic in the hands of workers. It is usually a weapon of last resort, used when negotiations to reach an amicable settlement which balance workers’ and employers’ interests have failed. Without the right to strike, the process of collective bargaining between workers and employers would amount to mere collective ‘begging’, as a German Labour Court once pointed out in the 1980s.

However, unlike in other EU countries, a fundamental right to strike does not exist in the UK, rather a strike is considered to be an exception to normal contract and tort law (and as we know exceptions are much easier to revoke than a fundamental right). For example, English law does not suspend the labour contract (and the obligations in them) during a strike, as is the case in many other European countries. In effect, striking in the UK is in itself a breach of contract.

My point here is also that the legal framework regulating (or rather dissuading) strikes in this country is already highly complex, cumbersome and very costly for the unions to organise. As a result of this, employers have ample possibilities and opportunities to stop a strike through seeking preemptive injunctions, which tend to be granted easily by the courts. Unions and workers are, furthermore, not immune from legal action from employers seeking damages if they do not abide to these stringent rules. They can even be prosecuted for it, potentially incurring criminal penalties including imprisonment. Unsurprisingly, a comparative study into the right to strike across the EU is quite damning for the UK:

“the situation of the right to strike in the United Kingdom is the most difficult and demeaning with respect to international standards. Making the strike hostage of the employer means, it must be stated very clearly, to delete that right. It is no coincidence that among the EU countries the UK has the lowest percentage of its workforce covered by a collective agreement (only 35% of UK workers are covered by a collective agreement).”

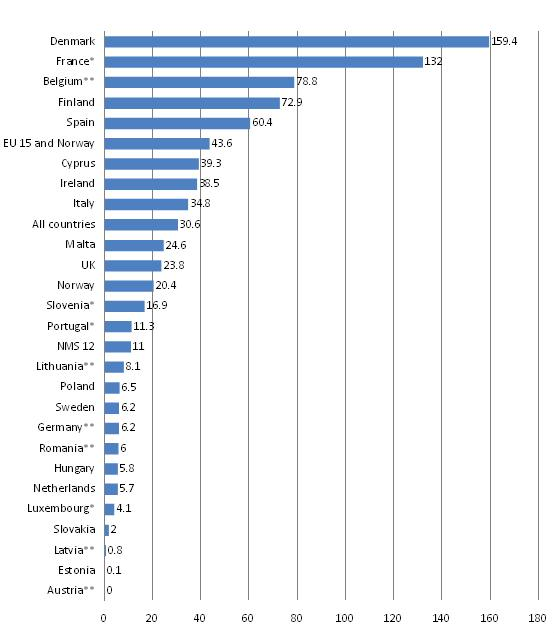

Given the stringent rules to strike, the punitive legal system and the relatively low level of union membership, strike action tends to be very low in this country compared to other EU countries (see also this blog article).

Figure 1: Working days lost through industrial action per 1,000 employees, annual average 2005–2009

Source: http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/eurwork/comparative-information/developments-in-industrial-action-20052009

Note: * average of 2005–2007; ** average of 2005–2008. ‘All countries’ is average of 25 countries; ‘EU 15 and Norway’ is average of 15 countries; ‘NMS 12’ is average of 10 countries.

In other words, this renewed attack on workers rights and the ‘freedom’ (rather than the right) to strike, is part of a broader ideological provocation by the Tory-led government geared towards undermining the rights and protections of workers in this country. Despite the fact that the government claims the contrary, it clearly and unambiguously represents the interests of capital, of employers, and of the rich rather than those of ordinary working people or, more generally, of the weak in society. This proposed anti-workers’ rights legislation is just one of the many articulations of this.

It is Orwellian newspeak to claim that the Tories are the party of working people and at the same time curtail the rights of these same working people. Furthermore, it is not industry or the services sector, but rather the public and transport sectors that strikes the most, which are both mostly under control of the government. In other words, making striking more difficult is also a weapon in the fight between the government as an employer and its employees demanding better working conditions.

The French saying that ‘le pays réel’ and ‘le pays légal’ are two different things expresses the idea that laws are one thing but what people actually do or consider legitimate is another. The history of social change learns us that laws to restricting rights, contention and protest have always been there, and they have never stopped people to test and resist these legal restrictions put in place by the capitalist liberal state.

It will thus be up to workers and militant syndicalists to reject and contest these legal barriers through direct action, thereby exposing the increasingly repressive tactics of the neoliberal state in its efforts to stifle all forms of dissent against it. However, given the restrictive legal regime in the UK and the impossibility to strike for ‘political’ reasons, this will require courage and dedication from workers and syndicalists alike.

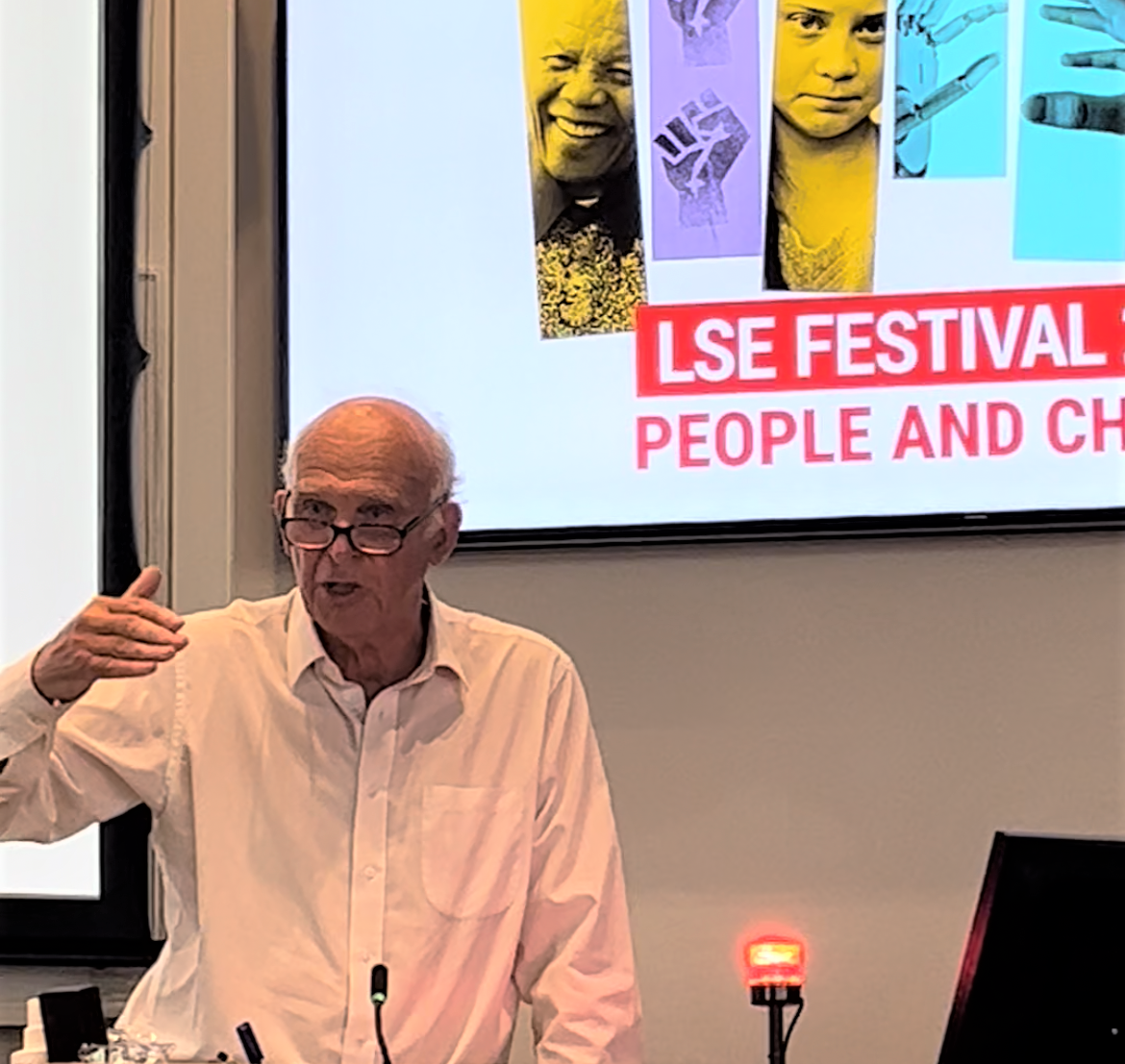

Bart Cammaerts is Associate Professor in the Department of Media and Communications at the LSE. He has recently written an academic article on the discursive war of position between neoliberalism and its alternatives, entitled: ‘Neoliberalism and the post-hegemonic war of position: The dialectic between invisibility and visibilities’. This article has been published in the European Journal of Communication.

Bart Cammaerts is Associate Professor in the Department of Media and Communications at the LSE. He has recently written an academic article on the discursive war of position between neoliberalism and its alternatives, entitled: ‘Neoliberalism and the post-hegemonic war of position: The dialectic between invisibility and visibilities’. This article has been published in the European Journal of Communication.

(Featured image credit: Roger Blackwell CC BY 2.0)

One would assume that Bart Cammaerts (BM) know what is included in the proposed union bill, but he does not mentined in a single word what is the substance of the bill or how it differs from the existing rules and their predessors or why it must therefore be opposed. One therefore comes to the conclusion that he wants the bill opposed for no other reason than it originates from within the Tory party rather than for any objective reasons. It would strengthen his arguments immeassurably if he could enlighten us in these areas. He says that it will “be up to workers and militant syndicalists to reject and contest these legal barriers through direct action”. Why just these groups of people? If this proposed legislation is such a fundamental attack on established rights then surely it should be opposed by every right minded, disent citizen. And what is meant by “direct action”? One assumes it is not enough for BM to change things through the ballot box. Furthermore I do think that people in this day and age will see the “repressive tactics of the neoliberal state” as a necessity to protect them against destructive trade unions. My final comments is that in all this BM totally ignores the consumer ie those who rely for their existence on the produce from manufacuring and on efficient service from industries such as the transport industry. And he also totally ignores the sometimes destructive effect of strike action. In my view Arthur Scargill and the NUM did more to annihilate the British coal industry than anything Margaret Thatcher ever did. When an industry is on its knees strike action is the last thing that is needed. Unionists need to find other ways (and preferably pieceful) means to confront employers. PS: As a professor one assumes BM knows the distinction between “learn” and “teach”, see 9th paragraph, line 3.