New data by the Electoral Commission on party funding shows, among other things, that Labour raised a record-breaking £16m in a year through membership fees alone, while the Conservatives received more money from bequests than from living members. Sam Power explains what these figures tell us about the state of play in UK party politics, and how they compare with previous years.

New data by the Electoral Commission on party funding shows, among other things, that Labour raised a record-breaking £16m in a year through membership fees alone, while the Conservatives received more money from bequests than from living members. Sam Power explains what these figures tell us about the state of play in UK party politics, and how they compare with previous years.

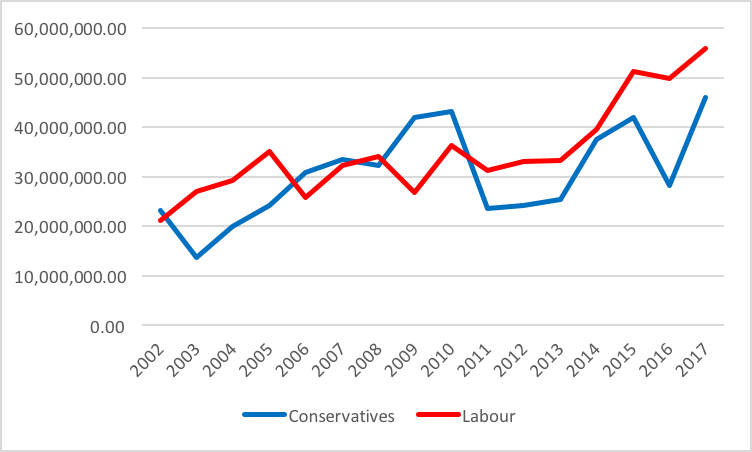

In late August 2018 the Electoral Commission released the annual accounting figures of all major parties for 2017. Every year this batch of data tends to cause (brief) excitement, with various media narratives taking hold about what it can tell us. This year was no different. Did Labour really raise £10 million more than the Tories? Do these figures reinforce an existential crisis facing the Tory grassroots? Using figures dating from 2002, I’ll unpick what they do, and do not, tell us about the state of play in British party politics today.

How much did each party raise?

As figure 1 shows, Labour kept up their streak from 2010 of out-raising the Conservatives by, as reported, just under £10 million. This figure was actually considerably down on 2016 where Labour’s advantage stood at over £20 million. We should be a little wary of reading too much into this. 2010 was, of course, the year that the Conservatives became the party of government. As such since 2010, Labour have been in receipt of considerable amounts of Short Money (which is money provided by the state to parties not in government). In 2017 Labour’s Short Money return was £7,427,000, as opposed to the Conservatives who received just £562,000 in grants.

Figure 1 Total party income (Conservatives and Labour), 2017

How much of this was through the membership – and does it matter?

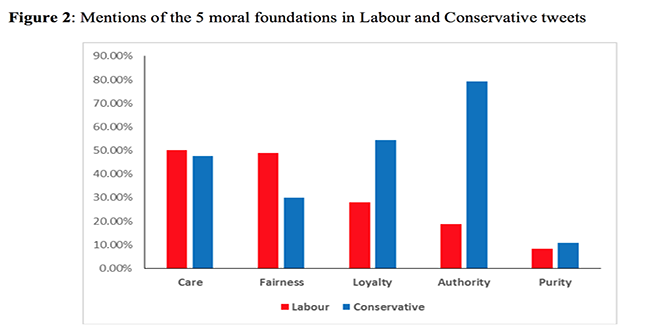

The most impressive feat of Corbyn’s Labour has been the amount the party has been able to raise through membership subscriptions. Figure 2 highlights the stark increase in this form of income from 2015 onwards – from £5,971,000 in 2014 to £16,165,000 in 2017. Put another way, in 2017 membership fees accounted for 29% of total party income. It is often discussed that Jeremy Corbyn’s organisational and political strength comes from the loyal membership; these figures show that they also provide a significant amount of income to the political party. Yet, they still only provide 29% of total party income. Therefore, whilst impressive, these figures also represent a stark reminder that even parties with a historically high membership cannot rely solely on it for their money.

Figure 2 Labour Party income (membership fees, grants, donations and fundraising, other income), 2002-2017

The Labour membership numbers are all the more impressive when compared with those of the Conservative Party (Figure 3). Whilst Labour raised over £16 million in 2017, the Conservatives only raised £835,000 – this has been about the standard from 2011 onwards. Indeed, so low is the membership income that a number of commentators noted that dead people (in the form of legacies) had actually donated more to the Conservative Party than their (barely) alive and kicking membership. This, on the face of it, is both accurate and quite funny but should be taken with a rather large grain of salt because the Conservatives raise, spend, and report the vast amount of their income at constituency level. Other amounts can therefore be found in local association which means that the actual membership income stands at about £4 million.

One might suggest that the reasons journalists are, for example, required to speculate over the number of Conservative Party members is that the party routinely do not include these figures in their accounting returns. Furthermore, common accounting standards and practises – a change that has been suggested by the Committee on Standards in Public Life – might make returns a little easier to understand in context. If a number of people struggle to comprehend something, there’s a case for making that thing easier to understand.

Figure 3 Conservative Party income (membership fees, grants, donations and fundraising, other income), 2002-2017

This misunderstanding also speaks to a broader problem of equating membership income with membership figures. They are not one and the same. For example, the membership of the Labour Party fell from 248,000 in 2002, to a nadir of 156,000 in 2009, before rising back to approximately 193,000 in 2014. Figure 2, however, shows that membership income continued on a slight incline in this period. Political parties can, within reason, make their membership income work for them as and when they need it. Membership income being at a low (or high) level is not necessarily indicative of party weakness (or strength).

Donations are becoming less cyclical, but that’s only because British politics is

Finally, one thing we know about political party funding is that it is cyclical in nature. You tend to get donation peaks in (general) election years and troughs in those without. Analytically speaking, this means we should always be wary of reading too much into figures from a single year, particularly when that year is an election year. However, the recent data seems to show that this cyclical pattern is less defined than it once was (see the above figures). This may well be because British politics just isn’t as cyclical as it once was – since 2014 we’ve been in almost constant election mode. If all remains calm, the 2018 returns may well be a useful guide to understanding whether, in political finance terms, the past three years have been a blip or represent the new normal.

______________

Sam Power is Associate Tutor in the Department of Politics at the University of Sussex and Research Associate at the Sir Bernard Crick Centre for the Public Understanding of Politics, University of Sheffield.

Sam Power is Associate Tutor in the Department of Politics at the University of Sussex and Research Associate at the Sir Bernard Crick Centre for the Public Understanding of Politics, University of Sheffield.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).