A century ago, Britain entered into a war against Germany and its allies in what would become known as the Great War, with millions of young men from all sides killed. At the time discussion on whether to enter the war centred around ‘honour’, and its invocation worked: The erstwhile opponents of intervention – radicals and advanced liberals, labour politicians and trade unionists, feminists and even pacifists – embraced the demands of honour and had a change of heart. One lesson from all this might be to reshape the concept of honour, writes Robin Archer.

For Britain, the First World War was a war of choice. And until just before the outbreak of hostilities, it was quite unclear what that choice would be. You would never know from the current commemorations. The BBC’s most serious attempt to look at the decision for war acknowledged that there was a choice, but presented it as one between standing up to autocracy (presented by Tory A – Max Hastings) and imperial preservation (presented by Tory B – Niall Ferguson). In fact, the debate in Cabinet – the debate that settled the issue – was between liberal imperialists who supported intervention and liberal radicals who opposed it. The radicals were hardly a fringe force. Until the very eve of the war they were widely thought to command a majority in the cabinet.

With its ruling Liberal party and its strong tradition of anti-militarism, Britain was the most equivocal of the European great powers and the slowest to commit to the war. On 1st August the Cabinet actually decided that it would not send an expeditionary force to France. As late as 2nd August, Prime Minter Asquith feared that three quarters of Liberal Party members were opposed to war and that his Cabinet could split.

It was these radicals that Foreign Secretary Grey had to convince when he rose in parliament on 3rd August 1914 to set out the case for war. His speech was interlaced with observations about interests and treaties. But it was questions of honour that provided its red thread. The nub of his argument was that if Britain were to “run away” it would lose “all respect”, and that that was more important than any other consideration. With war underway, the Prime Minister confirmed the centrality of honour to the government’s decision. Obligations, honour, infamy, provocation, disgrace, the good name of the country, and respect: these were the terms in which Asquith made his case. “What are we fighting for,” he asked. The answer was first and foremost, “to fulfill … an obligation not only of law but of honour.” Conservative leader Bonar-Law agreed. So did the Times. At issue, its headline declared, was “The Honour of the People.”

Even enduring opponents confirmed the centrality of honour to the decision for war. “If the nation’s honour were in danger we would be with him.” insisted Labour leader Ramsey MacDonald, in response to Grey’s speech. But, he continued, “there has been no crime committed by statesmen of this character without those statesmen appealing to the nation’s honour. We fought the Crimean war because of our honour. We rushed to South Africa because of our honour. The right hon. Gentleman is appealing to us today because of our honour.” Honour “is always the excuse,” agreed Labour’s Keir Hardie. “We shall look back in wonder … at the flimsy reasoning.” Three days later, Labour decided to vote for war credits and MacDonald resigned as leader.

The concept of honour was once closely related to the practice of dueling. Dueling was already an anachronism in the English-speaking world. But the honour code, with its connection to common sense notions of manliness, remained a powerful force. The essence of the code lay in the willingness of a man (and, by extension, a nation) to engage in physical confrontation to avert a loss of reputation – a willingness that must eschew the calculation of risks or weighing of reasons.

The invocation of honour worked. With remarkable frequency, the erstwhile opponents of intervention – radicals and advanced liberals, labour politicians and trade unionists, feminists and even pacifists – embraced the demands of honour and had a change of heart. In Cabinet, Lloyd George was the potential opponent whom Asquith and Grey feared most. But by September he could be found declaring that fate had reminded Britons of “the great peaks of honour we had forgotten”. After an initial stunned silence, Labour and the TUC also accepted that Britain was “fighting to maintain its honour”. In perhaps the most extraordinary volte face, Emmeline Pankhurst and the WSPU rallied to the government, and organised women to hand out white feathers to unenlisted men. Even the Quaker president of the venerable Peace Society declared that avoiding war would have been “dishonorable and discreditable”.

Liberal intellectuals played a particularly important role as their arguments provided a template for many others. Oxford Professor Gilbert Murray was a leading public intellectual. On 3rd August he was publishing a letter demanding that Britain remain neutral. Soon after, he wrote a widely circulated pamphlet explaining why Britain’s honour demanded war.

Why did the language of honour resonate? A major reason was its pervasiveness in Edwardian culture. It was inculcated by the elite Public schools, whose Old Boys commanded the high offices of state. It was inculcated by the Boy Scouts and similar organizations, which together attracted perhaps 40 per cent of adolescent boys. And it was a central theme in widely circulated Boy’s Own magazines and popular children’s books on model lives, like that of the ubiquitous General Gordon.

This explanation places the whole phenomenon reassuringly in the past – a last terrible trumpet blast from the long nineteenth century. However, when the United States entered the war in April 1917, the language of honour loomed large there too, despite its far more egalitarian and democratic political culture. Of the 25 Senators who contributed to the Congressional debate on the declaration of war, 21 invoked the notion of honour. In a typical example, Senator Hardwick (Georgia) argued that Americans “want peace, but not peace at the price of having our national honor sullied … [and] permitting the very name American to become a term of derision and reproach.” This language was not peculiar to the South. Three-quarters of the Senators who invoked honour were from outside that region. By delinking honour from the class indignities of a feudal social order, the democratisation of the honour code had given it a new lease of life.

Whether in Edwardian Britain or egalitarian America, appeals to honour sought to trump all other considerations of prudence, costs and benefits, and the balance of reasons. Partly underwritten by notions of manliness, honour claimed a standing beyond interests, beyond politics, beyond ideology, beyond morality, and even beyond reason. Like the exercise of authority, the appeal to honour demanded the surrender of judgment and compliant action.

The word ‘honour’ is now out of favour. But these kinds of trumping arguments and the honour code’s concern with national respect and reputation are still with us. Britain’s decisions to participate in the Great War in 1914 and the war in Iraq in 2003 share some similarities: the widespread opposition to intervention, especially among the government’s own supporters; the supine posture of the Cabinet, with only two resignations in each case; and the persistent concern that secret diplomacy (between Grey and France and between Blair and the United States) had determined the outcome. The decision for war in each case also provides evidence of the continuing salience of honour-style trumping arguments. What will other states think of us if we “retreat now” and “turn away at the point of reckoning”, said Prime Minister Blair, in concluding his case-for-war speech to parliament on 18th March 2003. “To debate but never to act … is the worst course imaginable”. It would, he said later, have left Britain and its allies “humiliated”.

Commemorations of great formative events are not mere recollections. They invariably emphasise the salience of particular sentiments and lessons, which they seek to preserve, promote and project into the future. What centennial lessons should we glean from the role of honour in the onset of catastrophic conflicts like the First World War?

One lesson might be to reshape the concept of honour. Ramsey MacDonald was already seeking to do this. He met with little success. But a century later we can draw on additional examples – like those associated with Gandhi, and King, and, in a somewhat different way, Havel – each of which provide celebrated models of dissident rather than warrior conceptions of honour.

But perhaps the still deeper lesson is that we should set aside the notion of honour altogether. We could reject its embrace of uncalculating confrontation, when reputation and respect are at stake, and repudiate its demand for relegation of the reason. “Honour has come back, as a king, to earth” wrote Rupert Brooke, the doyen of the young British war poets in 1914. Perhaps its reign should end.

For more, listen to Robin Archer’s LSE public lecture on this topic, delivered as part of the LSE’s Ralph Miliband programme.

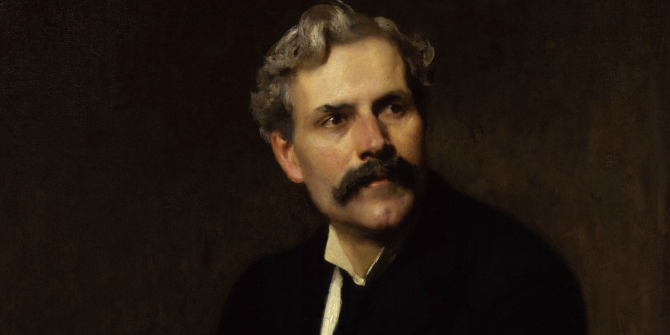

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image: Portrait of Ramsay MacDonald, now at the National Portrait Gallery

Robin Archer is Associate Professor (Reader) in Political Sociology at the LSE.