In a climate where there is high English public dissatisfaction with the constitutional and social status quo, one would be inclined to expect that the only major ostensibly federal political party would be in their element brandishing a comprehensive alternative. But Adam Evans argues that, on the contrary, the Liberal Democrats lack a clear vision when it comes to the English question.

In a climate where there is high English public dissatisfaction with the constitutional and social status quo, one would be inclined to expect that the only major ostensibly federal political party would be in their element brandishing a comprehensive alternative. But Adam Evans argues that, on the contrary, the Liberal Democrats lack a clear vision when it comes to the English question.

For a country which prides itself on having a political tradition of evolution rather than revolution, a striking feature of British politics in recent years has been a quiet revolution in England. The people of England, it has been traditionally assumed, have embraced a British, rather than an explicitly English identity. The Future of England research project between the IPPR and Cardiff and Edinburgh Universities and the 2011 Census results have radically challenged this longstanding convention, revealing that Englishness is now the identity of choice for the majority of people in England, both when considered on its own and as part of a dual identity. Not only is Englishness seemingly on the rise, but it is an increasingly assertive identity. A disconcerted and increasingly disaffected identity toed to an overwhelming English public dissatisfaction with the constitutional and social status quo in post-devolution Britain.

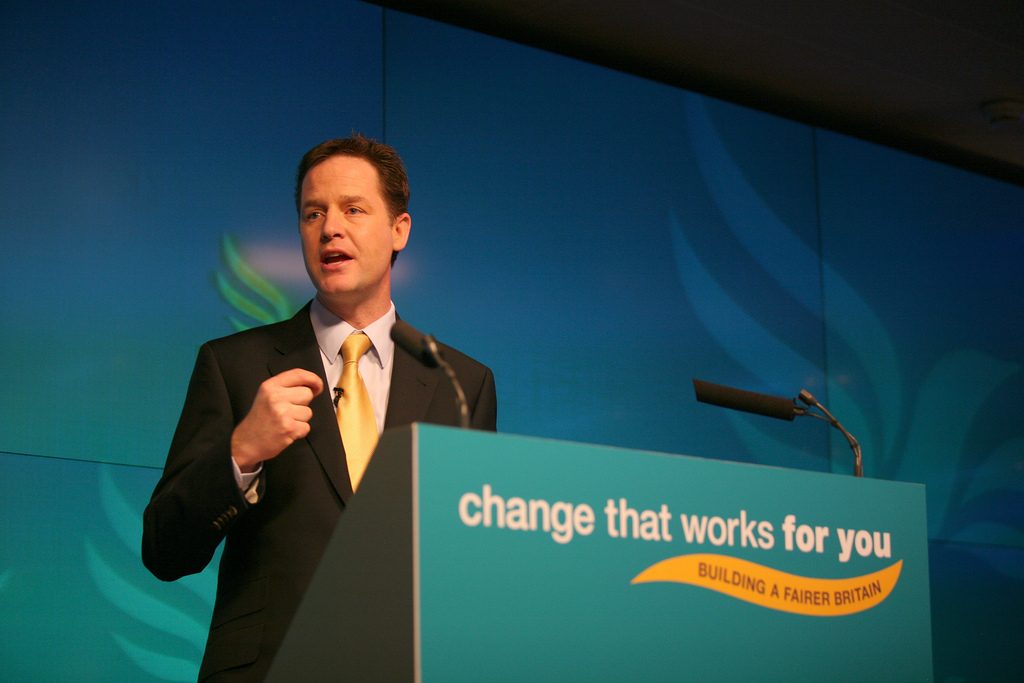

In a climate where the English majority appears to want reform, one would be inclined to expect that the only major ostensibly federal political party in Britain, the Liberal Democrats, would be in their element brandishing a clear and comprehensive federal solution to the English Question. In this article I argue that despite the recent conference endorsement of Power to the People, the Liberal Democrats have still not provided a clear and decisive response to “the English Question”. This policy gap calls into question the strength of the party’s commitment to federalism more generally.

Power to the People, the latest Liberal Democrat policy paper on the constitution, starts promisingly enough as a declaration of the party’s commitment to federalism:

“our vision as Liberal Democrats is of a federal United Kingdom within a democratic Europe.”

Indeed it goes on to state the party’s intention “to entrench Home Rule for all the nations and regions of the UK,” a commitment that includes an answer to the English Question as the document goes on to acknowledge more explicitly:

“to break the continuing impasse of the ‘English Question’ we set out a “road map” for a transition to a federal UK that recognises asymmetries of demand for devolution across England.”

There can be no doubts about this whatsoever, the Liberal Democrats are clearly pledging to provide an answer to the English Question here. The solution, furthermore, that is built around “demand” i.e. the democratic demands of the English public.

The party’s supply side approach to a federal UK and an answer of the English Question is built around what the document calls “devolution on demand” through an “English Devolution Enabling Act.” This Act would allow, for example, Cornwall and either principal local authorities or coalitions of local authorities with singular or combined populations of a million or more people to become a devolved legislative assembly (in two tier areas the policy document argues that the support of all the District or Borough councils affected by a 2/3 majority would be required). “Clear public support” would be required for such a move, a phrase that strongly implies that a referendum would be required. While the document calls these bodies “legislative assemblies” it is rather vague as to exactly what powers would be offered, although it is clear that the party envisages an asymmetric process of devolution. Furthermore, fiscal devolution would not be on the table, at least initially.

This is the federal party’s answer to the English Question. It is also essentially regionalism mark II, a policy that commands miniscule support among the English public. Since the 2004 North East of England referendum, when regionalism was defeated by a four to one margin, continued attempts at the centre to re-invent regionalist devolution have been consistently rejected by the public.

This was displayed most graphically in 2012 when eleven referenda were held in England’s largest local authorities on the question of having a directly elected Mayor. The suggestion was that the UK Government would then invest these Mayoralties with greater powers over transport, enterprise and local infrastructure. However, in the finest traditions of the best-laid plans of mice and men only one local authority area, Bristol, actually voted in favour of creating a directly elected Mayor (in Doncaster, the only other area to vote yes, the referendum was on the question of retaining their Mayor). Major unitary authorities such as Manchester, Birmingham and Nottingham rejected this offer of Mayoral devolution and in Liverpool and Leicester the adoption of a directly elected mayor only came about because the council chose to bypass a referendum entirely.

Whether in the form of a regional assembly or as enhanced Mayoral local authorities, regionalist answers to the English Question have been consistently rejected by the English public. Indeed, in the recent Future of England survey, England and its two unions, only 8% of English respondents supported the idea of English regionalism, the lowest score of any of the governance options offered. The Liberal Democrats vision for England is not so much “devolution on demand” as devolution with no demand.

To be fair to the party, the English Question is not an easy one to answer. Politicians since Churchill have wrestled with the problem of containing England within a devolved United Kingdom. Its demographic, economic and material dominance of the United Kingdom means that if treated as a singular unit in a system of pan-UK devolution or federalism that it would be highly likely to overwhelm the federal level institutions. Questions of who out of the federal government and the English government would have the moral mandate would be a potential feature of federal UK politics and would be particularly to emerge in times of intergovernmental dispute.

Furthermore, there is no consistent evidence to suggest that a new English Parliament is what the majority of the English public wants; it polled only 20% in the last Future of England survey. England doesn’t want a new Parliament; it wants its Parliament, Westminster, back. English votes for English laws is the plurality choice according to both England and its two unions and the preceding Future of England research in The dog that finally barked. The difficulty for parties such as the Liberal Democrats is that far from being a quick fix, English votes for English laws is potentially a Pandora’s box, raising questions about what actually is an English law when there is no English only legal jurisdiction and when the current system used in the UK’s territorial financial governance, the Barnett formula, is based on spending decisions in England thus providing a mandate for MPs representing constituencies outside England to continue voting on English affairs. Furthermore, English votes for English laws would pose potentially fatal constitutional problems for unionists, particularly if bifurcation were to emerge after a General Election with one party having a net UK majority, but the opposition having a majority of English MPs. Such a scenario risks shifting majorities depending on the topic being debated and would effectively create a Parliament within a Parliament.

The English question is, thus, the Gordian Knot of British politics. But however intractable it may be, it is a question that is increasingly unavoidable to address. The constitutional status quo is the option of choice for barely a fifth of the English electorate (21% opted for this in the 2012 Future of England survey) and while there is no precise consensus among the English public, there is, as the authors of England and its two unions argue, “strong support for a form of governance that treats England as a distinct political unit.”

For the only party that supposedly believes in a federal United Kingdom, there is no excuse for the Liberal Democrats absence of vision when it comes to the English question. Far from being a failure isolated to Power to the People this has been a long running theme for the Liberal Democrats, a party which has largely delegated questions of territorial reform to the party in Scotland. Devolution on demand is the party’s latest sticking plaster, but it cannot hold while the English public continue to oppose regionalism in all its forms. The party’s failings on the English Question are a damning indictment for a party which claims to believe in a federal future for the United Kingdom. The result is not only that serious questions can be raised about how committed the party is to federalism, at a time when constitutional dynamics in the United Kingdom should make this a fairly propitious intellectual and political climate for federalists, but should perhaps also arouse doubts about the viability of federalism more generally in the UK when even a party that is ostensibly committed to such a reform has struggled so evidently with the concept.

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of British Politics and Policy blog or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Adam Evans is a PhD student based at the Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University where his PhD explores the 1919-1920 Speaker’s Conference on Devolution. He also has research interests in the Liberal Democrats and their territorial governance policies.

Adam Evans is a PhD student based at the Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University where his PhD explores the 1919-1920 Speaker’s Conference on Devolution. He also has research interests in the Liberal Democrats and their territorial governance policies.

Plenty of polls, such as one conducted by the BBC, have shown there is demand for an English Parliament. However politicians of all the main parties brush this aside and refuse to debate the matter. Regionalism/localism has been given plenty of attention and, as the article says, has been rejected by the English public.

That aside, the Tories got a majority of English seats at the general election on a manifesto that included taking action on the West Lothian Question. This is the next best thing to a referendum but still the Lib Dems pursue their regionalist agenda for a England and the Tories sit on their hands.

The real way forward is for England to have a referendum on an English Oarliament. That will settle the matter. It won’t happen of course because the Westminster politicians of all parties only hold referenda when they have confidence (albeit misplaced) in the result!

Considering the Cornish and their mouthpieces do not consider themselves English but rather Celt, it would therefore follow that any regionalisation of England would not have included Cornwall, you cant have it both ways, either your part of England and can be considered for regionalisation or your not. It will be interesting to see what happens should Scotland go it’s own way followed by Wales and Cornwall, I give it 15 years before you all come cap in hand to England to become members of a new Union, by that time England having it own Parliament for at least 10 years will not give up her independence. As a Londoner I don’t mind sharing the wealth of England around England, but I’ll be damned if would want to share anything with those that so desperately want to be independent of England, remember once your gone, your gone forever

It’s often said that there is little or no interest within what is commonly considered England for ‘regional’ devolution. This is not quite true however. 50,000 people signed a petition calling for a Cornish Assembly in 2002. At the time a Cornwall Council opinion poll put support for a Cornish assembly at around 55%. The petition was collected over a couple of months by some motivated volunteers before the age of social media. This 10% of our population met with the criteria set by Prescott for the government to investigate a ‘regions’ desire for devolution. New Labour decided to renege on this promise and ignore Cornish calls for an assembly. Various Liberal Democrat MP’s for Cornwall have defended the idea of Cornish devolution as well as campaigning for Cornish national minority status, funding of the Cornish language and democratic accountability for the Duchy of Cornwall. Perhaps the last example of this being Dan Rogerson’s Government of Cornwall Bill. It should also be noted that the Green party, amongst others, also supports Cornish devolution. The last PLASC data for Cornish schools showed that 46% of children would choose Cornish to describe their identity rather than English, British or some mixture.

The Cornish Constitutional Convention: http://www.cornishassembly.org/

The Council of Europe’s Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and the Cornish: http://www.scribd.com/doc/59678181/Cornish-Minority-Report

The Liberal Democrats hate England and all things English almost as much as do Labour and Conservatives. An English parliament with a return to county councils with proper local powers is what is needed.

Here’s a thought. Glasgow has shipbuilding because of the United Kingdom. Portsmouth does NOT have shipbuilding because of the United Kingdom.

Maybe the trade unions should take that discrepancy on board.