In past elections, undecided women were more likely to vote for the Liberal Democrats than undecided men, and decided male and female voters. In this post, Rosalind Shorrocks asks whether this pattern is likely to be repeated in the election in May.

With just under a month to go until the general election, polls tracking voting intention put Labour and the Conservatives neck and neck. They are both also doing similarly amongst men and women: most recent polls show that Labour has a narrow edge over the Conservatives with female voters, whilst the Conservatives have a small lead over Labour with male voters (see this poll of polls), but the differences are reasonably minimal.

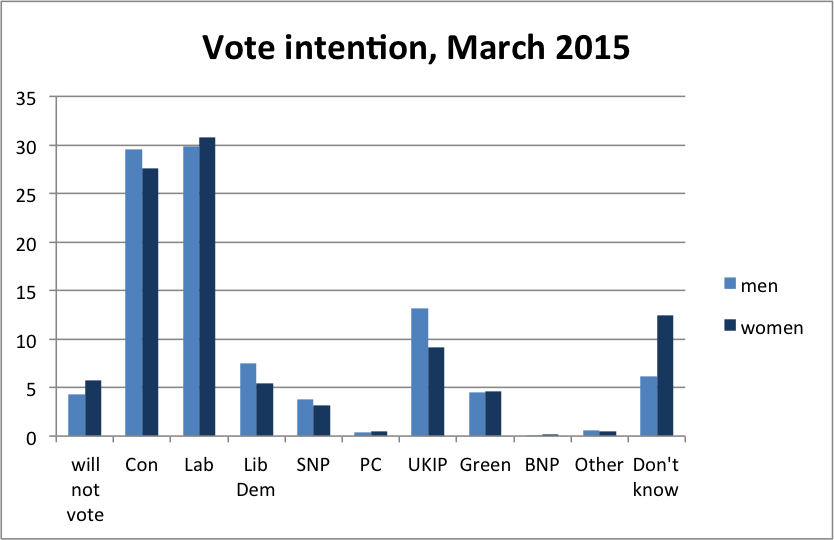

The latest wave of the British Election Study Internet Panel collected in March 2015 shows the same pattern: Labour are narrowly ahead, and while there is almost no difference in degree of Labour and Conservative support amongst men, women are approximately 3 percentage points more likely to support Labour than they are the Conservatives.

9.5 per cent of respondents in this wave of the BES said they did not yet know who they were going to vote for. In such a tight race, the behaviour of these undecideds could be crucial in determining the outcome of the election. This is also the category which shows the largest difference between men and women: 6.2 per cent of men say they don’t know who they will vote for, compared to 12.5 per cent of women.

Source: Preliminary wave 4 of the 2014-2017 British Election Study Internet Panel, collected 6-13thMarch 2015 (weighted). N: 16,626.

As pointed out by Dr Rosie Campbell here, although women have had a tendency to be less sure of their vote intention than men, they nevertheless only have marginally lower turnout rates – and indeed, the graph above shows that women are only slightly more likely than men to say they will not vote. This suggests that a fair number of those women who say they do not know who to vote for will, eventually, vote for someone. The over-representation of women in the don’t know camp implies that they outnumber men amongst the undecideds whom parties will wish to woo as we head into the last month of the campaign. In fact, the launch of Labour’s ‘Woman to Woman’ campaign in February, with its controversial pink mini-bus, could be seen as an attempt to win over undecided women.

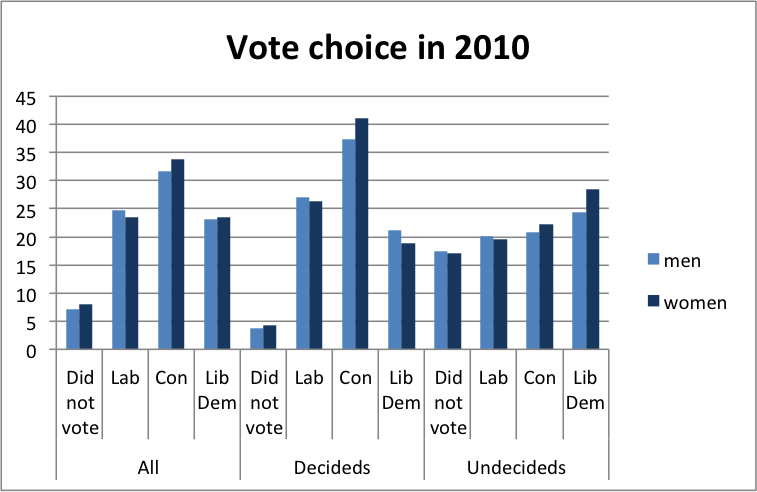

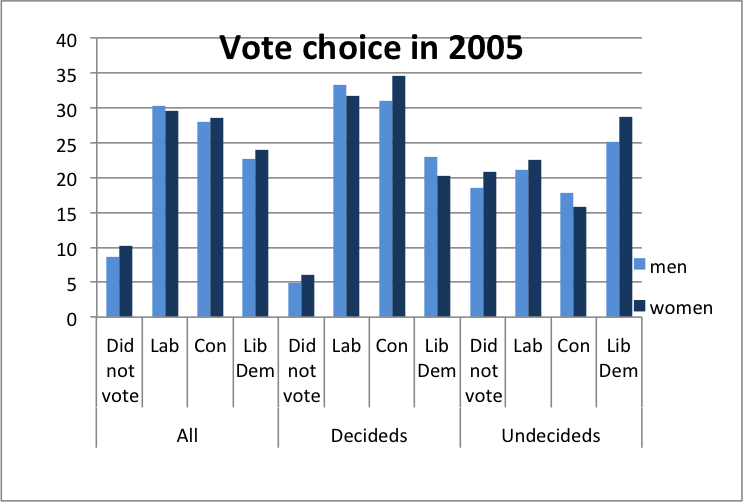

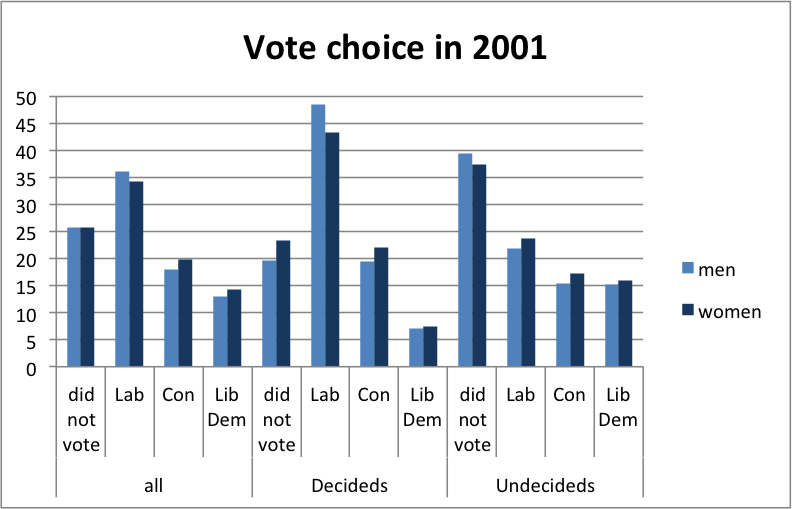

How do undecided voters behave once the general election arrives? Are there differences in the behaviour of undecided men and undecided women? Panel data from previous elections, collected by the British Election Study, can help us to understand the vote choice of those who were undecided in the short campaigns of the last three elections: 2010, 2005, and 2001. The graphs show data on eventual self-reported vote choice from the BES panel studies for these elections, for three groups of voters: all voters; those who had decided who to vote for in the campaign wave, and subsequently reported that they did vote for that party, the ‘decideds’; and those who had not decided who to vote for in the campaign wave, the ‘undecideds.’ A small group of voters (less than 1 per cent in 2010 and 2005, around 6 per cent in 2001) claimed to have decided during the campaign but then reported voting differently in the election; their eventual vote choice looks very similar to that for the undecideds below.

The data show that men and women tend to behave in similar ways to each other, with some exceptions. Labour and the Conservatives do much better with the decideds than with the undecideds, likely because they both have a core of party identifiers who can be relied upon to vote for them in election after election. Within the decideds, the Conservatives have tended to do better with women than men, and Labour better with men rather than women: an interesting pattern given 2015 voting intention suggests the reverse of this trend.

The Liberal Democrats do approximately 4-8 percentage points better with the undecideds than the decideds, for the converse reason that they don’t have a large troupe of party identifiers. This suggests that the Liberal Democrats might experience a rise in their vote share through the 2015 campaign as they win more undecideds than the other two main parties. Indeed, two election forecasters, www.electionsetc.com and www.electionforecast.co.uk are predicting the Liberal Democrat final vote share to be higher than that in current polling. Peter Kellner of YouGov has also noted that the Liberal Democrats get a boost out of the campaign period.

In two of the last three elections, 2010 and 2005, undecided women were more likely to vote Liberal Democrat than both undecided men, and decided men and women. In 2010, undecided women were over 10 percentage points more supportive of the Liberal Democrats than decided women, whilst undecided men were only 3 points more supportive compared to decided men. In 2005 these figures were 8 and 2 points for women and men respectively. The Liberal Democrats seem particularly good at generating votes from women who at the start of the campaign do not know who to vote for, compensating for the fact that they tend to do slightly better with decided men than with decided women. The March 2015 BES voting intention data shows this latter gap continues for the current election, though it is small with men 2 points more likely to say they will vote Liberal Democrat than women.

Source: British Election Study 2005-10 panel, 2010 campaign and post-campaign waves. N: 2,781

Source: British Election Study 2005-10 panel, 2005 campaign and post-campaign waves. N: 2,231

Source: British Election Study 1997-2001 panel, 2001 campaign and post campaign waves. N: 2,288

Unsurprisingly, those who are undecided during the campaign are much more likely to fail to turn out in the election; in 2001, with the lowest electoral turnout in the post-war era, the likelihood of an undecided voting for a particular party was lower than the likelihood they would just not turn out to vote. There are no consistent differences between men and women in the proportion of undecideds who eventually decide not to vote, and the differences there are tend to be very small. However, since women outnumber men amongst the undecideds, the actual number of them failing to turn out likely outnumbers men, even if the same proportion of men and women don’t eventually vote. This could contribute to the marginally higher abstention rate amongst women.

Overall, the lesson from previous elections is a positive one for the Liberal Democrats. Not only do they do better with those who have historically been undecided during the short campaign, they also do comparatively better with those who make up the largest group within the undecideds: women. However, they should be very cautious in their optimism. Opinion amongst the undecideds in wave 4 of the 2015 BES is not favourable to the Liberal Democrats, reflecting that this year is a very different electoral context to the previous elections examined here. Excluding don’t knows, 48 per cent of them say they are very unlikely to vote Lib Dem (compared to 49 per cent for Conservatives and 43 per cent for Labour), including 40 per cent of men and 55 per cent of women. The previous success the Liberal Democrats had with undecideds, and undecided women in particular, may well not be repeated this year.

Rosalind Shorrocks is a DPhil student in Department of Sociology, University of Oxford, specialising in gender and generational differences in voting behaviour and political attitudes.

1 Comments