While those who have studied at university typically have more liberal social and cultural attitudes and more conservative economic attitudes than those who have not, we know little about the causal influence of university graduation on the attitudes of British graduates. Elizabeth Simon suggests that university study has, at most, only a very small direct ‘liberalising effect’ on socio-political values.

While those who have studied at university typically have more liberal social and cultural attitudes and more conservative economic attitudes than those who have not, we know little about the causal influence of university graduation on the attitudes of British graduates. Elizabeth Simon suggests that university study has, at most, only a very small direct ‘liberalising effect’ on socio-political values.

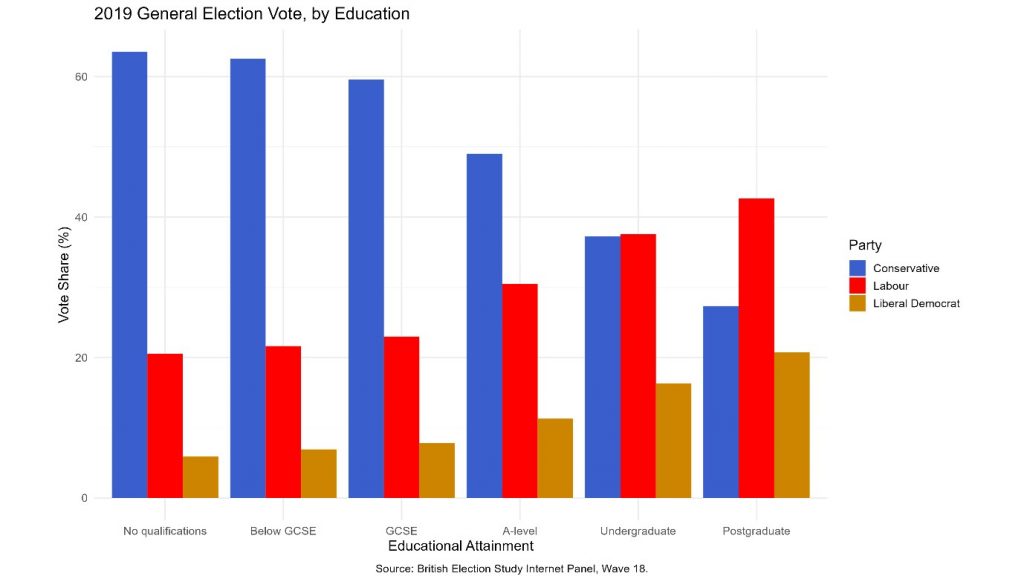

A stark educational divide has emerged in British politics. This is illustrated clearly by the British Election Study data (presented in Figure 1), which shows large ‘educational gaps’ in voting for the three main British political parties at the 2019 general election. Increasingly highly educated individuals were clearly more likely to vote Labour and Liberal Democrat, and less likely to vote Conservative, in 2019 than their less educated counterparts. Yet, the relationship between educational attainment and vote choices in Britain is not strictly linear. Rather, as I show in this blog post, it is driven mainly by differences in the voting behaviours of those who have studied at university and those who have not.

Figure 1. The Educational Divide in the 2019 British General Election Vote

Source: British Election Study Internet Panel, Wave 18. By E. Fieldhouse, J. Green, G. Evans, J. Mellon & C. Prosser, J. Bailey, R. de Geus, H. Schmitt and C. van der Eijk (British Election Study Internet Panel Waves 1-21 (2021). DOI 10.5255/UKDA-SN-8810-1.

The educational divide in recent British general election voting is largely a consequence of the fact that educational groups tend to think differently. Those who have studied at university typically have more liberal social and cultural attitudes and more conservative economic attitudes than those who have not, and these distinctive socio-political values motivate them to vote for different parties than their less educated counterparts. While we know that British graduates vote differently because they think differently, we know little about why it is that graduates actually come to think differently in the first place.

There are several possible explanations for this. The first is that the experience of studying at university in itself causes individuals to develop a distinctive set of (il)liberal attitudes. Although there is scant evidence to suggest this is the case in the British context, this idea has gained much attention in recent years, with commentators increasingly claiming that professors at ‘woke’ HE institutions are ‘indoctrinating’ students with ‘leftist agendas’ and ‘liberal madness’.

It also seems quite plausible, however, that university study would have no direct causal influence on graduates’ attitudes. It may simply be that the kinds of individuals who possess these distinctive attitudinal positions are disproportionately selecting to enrol on degree programmes. This is referred to as the self-selection explanation. Additionally, it could be the case that university attendance shapes attitudes only indirectly. Graduates not only earn considerably more than non-graduates but are also more likely to be in employment. It may be by virtue of the more secure material position that a university degree affords, rather than their university experience per se, that graduates come to develop distinctive socio-political attitudes. This is known as the adult status explanation.

In my recent study, ‘Demystifying the link between higher education and liberal values: A within-sibship analysis of British individuals’ attitudes from 1994–2020’, I seek to discriminate between these competing explanations to uncover precisely why it is that British graduates tend to exhibit distinctive socio-political attitudes. I use data from the British Household Panel and Understanding Society surveys to estimate the effect that graduating from university has on British individuals’ gender role, environmental (cultural) and economic attitudes.

Like existing studies, my analysis controls for a host of factors (such as cognitive ability, parents’ attitudes and occupational status in adulthood) associated with the self-selection and adult status explanations. However, it also measures university’s effect on attitudes only among siblings who lived together in childhood – this ‘within-sibship’ analysis meant that a variety of unmeasured, pre-adult experiences which are constant among siblings within households could also be accounted for. This ensured I could better identify university graduation’s independent influence on attitudes. Exploiting the household structure of the data in this way allowed me to provide a uniquely robust estimate of the causal effect of university study on individuals’ attitudes.

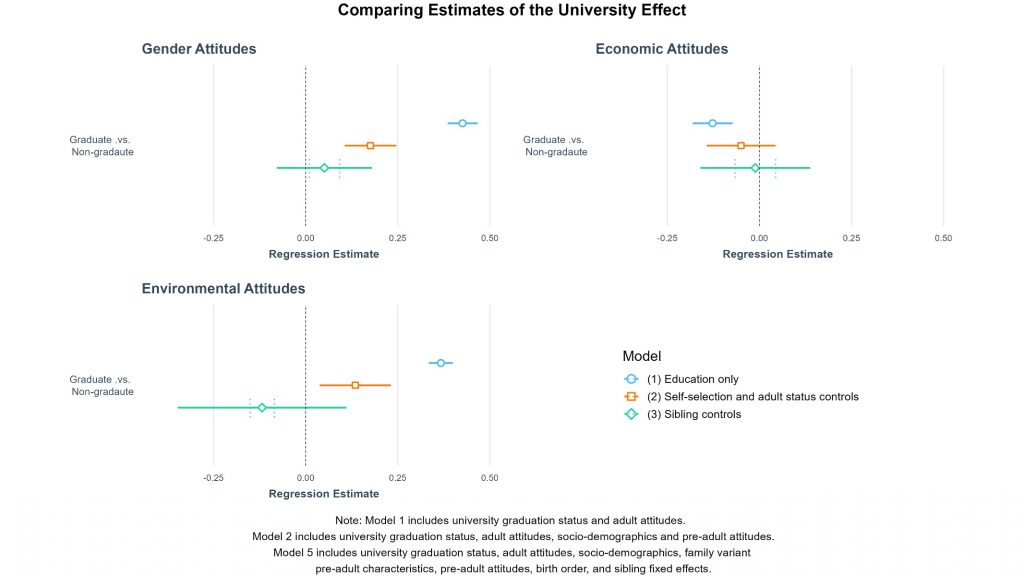

All attitudinal variables studied were coded such that higher values represented more liberal standpoints, these being gender egalitarianism, high levels of environmentalism (cultural attitudes) and left-wing economic attitudes, respectively. Positive estimates in Figure 2 therefore illustrate the liberalising effects of university study on attitudes.

The first stage of my analysis estimated the total effect of university graduation on British individuals’ attitudes. As expected, I found that graduates had considerably more liberal cultural attitudes, and somewhat more illiberal (or conservative) economic attitudes, than non-graduates (see Model 1 estimates, Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Effect of University Study on British Individuals Attitudes, 1994-2020

Source: Understanding Society/British Household Panel data. University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research. Understanding society: Waves 1-10, 2009-2019 and harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009 (13th ed., 2021). [Data Collection]. UK Data Service. SN: 6614, DOI: 10.5255/UKDA-SN-6614-18

I then moved on to isolate the independent causal effect of university study on these attitudes. After controlling for self-selection and adult status explanations (see Model 2, Figure 2) the estimate of university’s effect on economic attitudes shrinks so much as to become almost zero, and the 95% confidence interval for this estimate overlaps the zero (no effect) line. Clearly then, the link between university graduation and economic attitudes in Britain is not causal.

The same cannot be said of cultural attitudes. While Model 2 estimates are considerably smaller than Model 1 estimates, graduates still appear to have considerably, and statistically significantly, more liberal cultural attitudes than their less educated counterparts, even after accounting for self-selection and differences in adult status. Once the most stringent controls – which involve estimating the university effect between siblings only – are introduced in Model 3, however, I find the size of the ‘liberalising’ effect of university study on gender role attitudes shrinks substantially and is replaced by a small negative effect for environmental attitudes. In this final model, British graduates’ cultural attitudes are no longer statistically significantly different from non-graduates.

This finding could be taken as evidence that university graduation does not cause British graduates to develop distinctively liberal cultural attitudes. However, these within-sibship estimates of the university effect are much less precise than the others, as they are estimated on smaller samples (see the larger size of these estimates’ 95% confidence intervals). It is therefore important to consider whether the lack of university effect reported here stems from a genuine absence of effect as opposed to the fact that within-sibship estimates are too imprecise to be conclusive.

The dashed lines superimposed on Model 3 results show the confidence intervals that would have been estimated in the full (sibling and non-sibling) sample. The fact that these do not overlap zero in the cultural attitudinal models suggests the university effects estimated here would in fact have been statistically significant in a larger sample. It therefore seems most appropriate to conclude, based on the results of my analysis, that university study has a small direct causal effect on adult cultural attitudes in Britain, and that these effects are not always liberalising.

The largest university ‘liberalising effect’ identified in my within-sibship models is for gender egalitarianism, at 0.05. Given that my attitudinal measures use 1-5 scales, this means that our gender role attitudes become on average just 1/20th of a scale point more liberal whilst at university. It is hard to argue that such small changes are likely to have any drastic real-world impact.

My research provides the most up-to-date understanding of the effect of university graduation on British individuals’ attitudes, having estimated this in the period 1994-2020. It shows, contrary to popular assumptions about education’s liberalising role, that the linkage of educational attainment with socio-political values in Britain is largely not causal. Rather, this association is predominantly driven by a self-selection effect, whereby those who experience pre-adult environments which encourage the formation of a particular set of attitudes disproportionately choose to enrol for university study.

My findings suggest that university study has, at most, only a very small direct ‘liberalising effect’ on our socio-political values. This has several important implications. These findings not only indicate that claims universities ‘indoctrinate’ their students with ‘left-liberal’ values have been greatly overstated. They also show that it is unlikely that British public opinion will grow substantially more liberal as decades of increasing university enrolment rates continue to alter the educational composition of the population.

Note: the above draws on the author’s published article in The British Journal of Sociology.

About the author

Elizabeth Simon is a PhD candidate working across the University of Southampton’s Social Statistics and Demography and Politics and International Relations departments. Her research focuses on how educational attainment shapes public opinion, electoral behaviour and wider society. She tweets as @elizabeth_sim0n.

Elizabeth Simon is a PhD candidate working across the University of Southampton’s Social Statistics and Demography and Politics and International Relations departments. Her research focuses on how educational attainment shapes public opinion, electoral behaviour and wider society. She tweets as @elizabeth_sim0n.

Image credit: Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash