Reforming the UK’s voting system will be one of the hottest issues in British politics over the next two years. Here Tony Travers, Patrick Dunleavy, Chris Gilson and Leandro Carrera offer the definitive simple guide to all you need to know about the top five alternative voting systems on offer.

1. First Past the Post (or ‘FPTP’ for short) – the current system in use in the UK since mediaeval times. The country is divided into local constituencies (voting districts) and an election takes place within each of these. The candidate who gets the largest number of votes in each constituency becomes the MP – they do not need to have majority support, just more support than anyone else. One party usually gets a clear majority of MPs and forms the government, but ‘hung Parliaments’ have occurred in 1974 and 1977-79, and now in 2010. If there is no majority, it is necessary for two or more parties to work together, or there is a minority government.

Incidentally, the ‘first past the post’ label is completely misleading because there is no fixed winning post. What you need to win a local seat is just a ‘plurality’, namely more votes than anyone else. So the more parties compete in each seat, the lower the winning ‘post’ gets. Consequently political scientists call this system ‘plurality rule’, a much more accurate label.

2. Alternative Vote (AV) – this system keeps the local, single MP constituencies but people vote 1, 2, 3 etc (instead of just using a X). Votes are counted in a more sophisticated ways and each MP must get a majority (50%+1) of the votes to be elected.

The key difference in the AV system from FPTP is that in each local contest voters fill in a ballot paper where they number the candidates in order of preference – that is, they put 1 for their first preference; 2 for their second choice; 3 for the party they like 3rd, and so on.

We count all the first (top) preferences that voters have given, as now. If any candidate gets majority support (i.e. 50% +1), they immediately win the seat. If not, the candidate who has the fewest 1st preference votes is knocked out of the contest, and we look at the second preferences of their voters, redistributing these votes to the remaining candidates in line with these voters’ number 2 choice. This process of knocking out the least popular candidate and redistributing their voters’ choices as voters intended continues until one candidate gets 50 per cent.

In the USA this system is called ‘instant run-off’ and this is a good summary of what AV does – it delivers a run-off election when no one gets an outright majority on first preference votes.

3. Alternative Vote Plus (AV+) – this is a variant of the Alternative Vote (AV) method, with most MPs elected locally using AV in single MP constituencies. But now extra MPs are also elected in multi-member seats at regional level. They go to parties that are under-represented in the local contests.

A large proportion of MPs (75% to 85%) are elected according to AV in local constituencies (see above). But now the remaining MPs are separately elected on a ‘top up’ basis for each region or county using proportional representation. Voters have two votes, for their local MP, and for a party list of candidates at the regional top-up level. We count the share of votes for each party in this top-up election, and elect MPs from the list of candidates for any party that has not already got enough MPs from the local contests, given their regional share of the votes. Candidates are elected in the order that each party has listed them – so the first seat goes to a party’s top candidate, its next seat to its second candidate, etc.

This system tries to match parties’ shares of all local and top-up MPs in each region to the (regional) votes for that party. But because there are far fewer regional top-up MPs than locally elected MPs, the system is at best ‘broadly proportional’ – it is very unlikely to produce results that closely match parties’ MPs to their vote shares.

4. ‘Additional Member’ System (AMS) – this is a more balanced and fully proportional system. Around half of MPs are locally elected, using FPTP as above. The remaining half or so (the ‘additional members’) are regionally elected using PR, so as to match every party’s share of MPs to their votes share.

The basic idea of electing two types of MPs is the same as the AV+ method above. Around half of MPs are locally elected in constituencies: here whoever gets the largest vote becomes the MP. But in AMS voters also have a second vote for regional top-up MPs. Candidates are put forward on regional lists by each party. We look at how many local seats a party has in a region, and at what share of the votes it has in this region: if it does not have enough MPs we elect more people from its regional list to bring it up to parity of MPs and vote shares. There’s a formula for doing this that works perfectly.

The one detailed point to notice here is that in some AMS elections (like the Greater London Assembly and Germany) parties have to get a minimum share of the vote to qualify for getting any MPs at all: usually the requirement is 5 per cent of votes. In other AMS elections (such as Scotland and Wales) the regions used for top-MPs are small enough already, so that this extra rule is not needed.

One for the nerds – AMS is often called ‘Mixed Member Proportional’ (MMP) in academic discussions and in New Zealand.

5. Single Transferable Vote (STV) – uses much bigger, multi-member constituencies (electing 3 to 5 MPS each) to give local seats to different parties. This is a fully proportional system that matches MPs to votes.

The number of constituencies is reduced (to a third or a fifth of the current number) and their size is increased, so that we can elect 3 to 5 MPs at a time in each local contest. As in AV above, voters mark their choices 1 (top choice), 2 (second choice), 3 and so on. If they like, voters can choose candidates across different parties, so as to exactly match their personal preferences. A complex counting process operates that allocates seats in an order to the candidates that have most votes, so as to get the best fit possible between party vote shares and their number of local MPs. Over the country as a whole the results should be proportional.

Want to know more about how this magic counting system works? These next two paragraphs are for you. We look at the votes and divide them by the number of MPs +1 This gives a ‘quota’, a vote share that guarantees a party one MP. (E.g if we count 100,000 votes and have 4 MPs to elect in a constituency, then the quota would be 100,000 divided by (4+1) = 20,000 votes). Any party with more than a quota gets an MP straightaway; a party that has two quotas, gets two MPs, etc. Every time we give the party an MP, we deduct that share of votes from its total.

When we’ve done this, there will normally be about half of the seats still unfilled. Here we shift into the AV method of knocking out the bottom candidate, and redistributing their votes (see above) – and we keep doing this until one of the parties still in the race has a quota and wins the next seat. We then deduct this quota from that party’s votes (as above) and carry on with the AV ‘knocking out the bottom candidate’ process until all the seats are allocated.

What difference will the systems make? Who benefits?

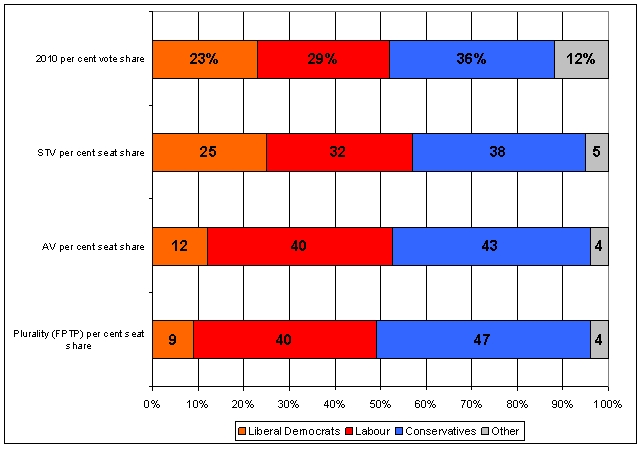

Our chart below shows the current ‘best guess’ of how the 2010 election would have turned out under the different systems.

* Source: BBC: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/election_2010/8644480.stm

Would you like to know more?

An accessible and British-focused account that dates back to the first wave of electoral reform in the UK is provided by Patrick Dunleavy, Helen Margetts and Stuart Weir, The Politico’s Guide to Electoral Reform in Britain

http://www.democraticaudit.com/download/ElectoralReform.pdf

A more recent but also more complex account is provided by Simon Hix, Ian McLean and Ron Johnston in a report from the British Academy:

http://personal.lse.ac.uk/hix/Working_Papers/Hix-Johnston-McLean-choosing-an-electoral-system.pdf

You say that the term “first past the post” is “completely misleading because there is no fixed winning post”. However the “post” is just end of the race – in this case, the end of the counting. Just as there is no “fixed speed” or fixed margin by which a rider wins a horse race, so too in FPTP you simply need to be ahead at the end.

It seems perfectly well named to me.

STV would seem the best system but it needs to be accompanied but a directly elected Prime Minister who forms his cabinet with people from outside elected parliamentarians. This will provide a check and balance between the legislative and the executive.

Given Prof Dunleavy’s recent post about London AV vs Aussie AV, I find it ironic that you didn’t make the distinction above! I know you are keen to have this as a ‘simple’ guide, but I think it would be useful to have the difference elucidated above. I sense that a lot of people will do independent research on AV in coming months, in order to navigate various disingenuous comments and vested interests that we keep reading about.

Correction to the above – the Tories actually received 34.6% in the Top-Up votes. Apologies for the typo.

Hi Patrick, thanks for the comments.

Yes, Regional Top-Up is a combination of AMS and TR, with a few improvements thrown in.

The problem with AMS is that it is essentially two separate systems bodged together somewhat inelegantly. The very fact that people split their votes demonstrates why it is a flawed system; people still don’t feel able to vote for their favoured party in a free manner. That is *not* a good thing IMHO. Because AMS uses FPTP separately to the top-up system, it still has all of the problems associated with FPTP (two-horse race, wasted votes etc)

Since people only feel free to vote as they would really like in the regional vote, this means that the proportionality of the result is limited to a small subset of the seats rather than the entire Assembly/Parliament.

For example, in the last London Assembly elections the Conservatives received 36.6% of the vote, which is presumably roughly the percentage of people who would like to vote Tory given a free choice of all parties. That should equate to 9 seats on the 25 seat Assembly. The Tories won 8 seats under FPTP, but then because the top-up system is completely separate, received a further 3 top-up seats, giving them two seats more than their support should justify. In other words, the system intended to provide an element of PR actually made the result disproportionate to what it should have been.

Because Regional Top-Up calculates the top-up MPs in proportion to the overall vote, it much better reflects the first choice of voters across the Parliament. It is also a simpler voting system and ends the two-horse race nonsense that AMS still encourages.

Obviously there needs to be a reform in the current system it seem ridiculous that the party holding the lease seats in the election appeared to hold the most power approaching first the conservatives and then labour. Clearly there needs to be an alternative method of allocating the first past the post which is fairer than the current system. From the results above depending upon the system the outcome of the election would have a different result. In order for this to change all parties or the majority would need to agree with the new proposed system. I not sure if you would ever get that agreement however a change is required to estabilish a fairer system.

Thanks to the most recent commentators.

Anthony – your ‘regional top-up’ system is essentially a version of the Additional Member System that gives voters only a single vote. So the voter has to try and guage how to ahcieve a local effect in the first past the post election, at the same time as producing an effect at the regional level – which is pretty impossible to do for many voters. E.g under a two vote system a centre-left person might vote Labour in the local constituency contest, but then Green at the regional level. Evidence from Scotland, Wales and London shows that between 25% and 40% of voters split their ballots like this – which your system would outlaw. There are no AMS systems that I know which use a single vote for these reasons.

By the way, AMS systems usually use X voting, one X being placed on the local ballot and one on the regional ballot. It’s only AV Plus that would use 1,2,3 voting on the local ballot, and X voting on the regional ballot.

Clay – thanks for the extra information you give on where Approval Voting has been employed. It seems to confirm that no country uses this for general elections. One powerful reason why Approval Voting may not work for national-level open elections is that it requires people to vote for all those candidates they approve of (withholding their votes from those they disapprove of) – hard to do if the people involved are not already well known to citizens. It’s for this reason that Approval Voting has been advocated more in closed organizational contexts, where electors have more chance of knowing all the candidates.

Student,

You said, “smaller parties would have gotten more votes with a more proportional system, even AV.”

This is wrong. Australia has had IRV in their House since 1918, and it is consistently two-party dominated by members of either the NatLibs or Labor. That is in spite of the fact that its Senate uses STV, and so the Greens typically get several seats (http://scorevoting.net/AustralianPol.html).

And AV is not “more proportional”. It is strategically identical to Plurality Voting. There will only be significantly less tactical voting when voters are already sure that the minor party candidate(s) don’t have a chance anyway. If you look at the last mayoral race in Burlington VT USA, there was a bloc of voters who preferred Republican>Democrat>Progressive, who could have gotten Democrat instead of Progressive if they had tactically/insincerely top-ranked Democrat. Since Burlington is so liberal that the Republicans are effectively the minor party (I looked in the history books and cannot even FIND the last Republican mayor they’ve had), these voters will quickly learn that it is a waste to vote sincerely for the Republican, and so they should always top-rank their favorite between the two “major” parties: Progressives and Democrats. Well, actually they won’t learn that, because after two IRV elections, voters repealed it in favor of PV.

Mr. Dunleavy,

Approval Voting has been used for large contentious elections. It is used to elect the secretary general of the United Nations, and the first four US Presidantial elections were done with a form of approval voting (http://scorevoting.net/Approval.html#history).

But you haven’t established the relevance of that issue. Bayesian Regret calculations show that Approval Voting behaves approximately as well with 100% tactical voters as Alternative Vote does with 100% sincere voters. So even if we assume that broader real-world use of Approval Voting would result in a worst case scenario, and IRV would magically have a best case scenario with no tactical voting, Approval Voting STILL performs as well as IRV. Make more realistic assumptions and Approval Voting far surpasses IRV.

http://scorevoting.net/BayRegsFig.html

You speak to the importance of ease of understanding and auditing – yet IRV is essentially the worst single-winner system in this regard. It cannot be sub-totaled in precincts (http://scorevoting.net/IrvNonAdd.html). And it empirically results in about 7 times as many spoiled ballots as PV, whereas Score/Approval Voting experimentally REDUCE spoiled ballots (http://scorevoting.net/SPRates.html). And it cannot be administered on ordinary dumb totaling PV voting machines — upgrades are needed, unlike with Score/Approval Voting (http://scorevoting.net/VotMach.html).

And, again, the fact that Approval Voting doesn’t require voters to believe a candidate CAN win in order to feel safe voting for that candidate, means that cash and other indicators of “electability” matter far less. For example, exit polling showed that 90% of the voters who claimed to prefer Green Party candidate Ralph Nader in the 2000 USA election actually voted for someone other than Nader. So if you take all the votes he earned through all the money he was able to raise, and all the moving speeches he delivered, and all the time he spent campaigning, it turns out that convincing people he COULD win (e.g. by announcing competitive fundraising, or earning significant endorsements via political favors) was at least 9 times as important. With Approval Voting, he could have gotten all those votes. Thus cash and major party nomination (probably the single biggest ingredients in proving electability) would be immediately less important.

People often think that IRV would have also fixed this, but they are wrong. It only fixes this problem in the case where the minor party has no chance of winning anyway. If you have a stronger minor party candidate, you want to bury him, as explained mathematically here:

http://ScoreVoting.net/TarrIrv.html

Clay Shentrup

San Francicso, CA

206.801.0484

I was hoping that you could add the Regional Top-Up system to your list of electoral systems please. There is much more about it here:

http://www.regionaltopup.co.uk

It is a considerably improved version o the Additional Member System that deals with all of the issues of PR. Every MP is elected in a constituency, no party lists are used, nearly every vote counts, the small parties get the MPs they deserve, the voting method is the same as now, people can vote for a party even if there is no local candidate and independent candidates can still stand.

It is the ultimate combination of FPTP and PR! 🙂

Thanks to everyone for the comments so far, all of which are helpful.

1. Kevin argues correctly that under AV+ as recommended by the Jenkins Commission, it would not be accurate to say that : “Candidates are elected in the order the party has listed them”. However, that is what currently happens in all Britain’s Additional Member System elections, of which AV+ is a variant (just with very few top-up seats). So our judgement is that if AV+ ever gets to be implemented, it will be implemented as we have described it, and not in every particular as Jenkins set it out.Frankly also AV+ is complex enough already to explain, without getting into more complexities on this aspect of how to go beyond simple party lists.

2. Eats-Wombats provides a link to the Electoral Reform Society, one of the largest and longest-lived members of the coalition of groups promoting electoral reform. Twenty years ago, ERS was a very single-minded backer of the Single Transferable Vote system, and this is still their top preference. However, in recent years their members have also voted to back AV+ and even AV as worthwhile changes and their website at http://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/ is a good place to visit to see fair-minded discussions of different systems (with still a preference for STV).

3. Clay Shentrup provides helpful links for two approaches to counting votes that we do not describe above, because they are not being seriously debated for adoption in the UK. Of the two the best known is Approval Voting, which has been much discussed in academic circles, but is not (I think) adopted for actual use anywhere in the world?

There are a huge range of theoretically possible voting systems now, many of which have analytically attractive properties and some of which are actually embodied in physical products – like missiles that ‘vote’ on which target to go for when confronted by multiple alternatives. The essential points to stress here are twofold:

(a) We are much better at counting now than before, especially because of computers. And of course we are far advanced on the mediaeval times when first-past-the-post was devised. But

(b) Practical voting methods for adoption at a top political level in any country need to have wide popular support and be easy to understand and to operate under practical conditions, including having an easy audit trail if things go wrong.

4. Student raises an important point – that any simulations of who would get what votes in a new system that are based upon behaviours under the old system will have significant limitations. We agree – and that’s why if you look in “The Politicos Guide to Electoral Reform” (free download link at the end the original article above) you will find a careful effort to ‘replay’ elections under the different systems, plus a strong health warning that dynamic effects arising from the introduction of a new system are still quite hard to forecast.

For all the talk about who benefits from a given voting system, it must be remembered that this election was fought under FPTP, and people could (and would) have voted different in a different system. There would have been less tactical voting than today, as votes would be less likely to be wasted. And it’s not just the distribution of votes between the three parties that dominates today that would change, smaller parties would have gotten more votes with a more proportional system, even AV.

Even more fundamentally, with PR there should be more than three parties to choose from. New parties could arise and enter Parliament, as the Greens have already done, or new parties could be formed from splits in the Labour, Conservative or Liberal Democratic parties, which all have an ideological diversity that is greater than in many other countries.

It should be noted that STV was first proposed in 1821, nearly a century and a half before most of the modern advances in voting theory. Reweighted Range Voting and Asset Voting are simpler and objectively superior according to various mathematical criteria.

http://ScoreVoting.net/RRV.html

http://ScoreVoting.net/Asset.html

http://ScoreVoting.net/PropRep.html

The single-winner form of STV, called “Instant Runoff Voting” in the US, and (ambiguously) “Alternative Vote” in the UK, is a very poor system that behaves roughly the same as FPTP (“plurality”) voting.

Score Voting (rating the candidates on a scale), is a better method. Its simplest form is Approval Voting, which is just like FPTP except that you can vote for as many candidates as you want to. It has the nice advantage over Alternative Vote, that voters NEVER have to fear supporting candidates they prefer to the front-runners.

E.g. say you prefer Brown>Clegg>Cameron, and head-to-head polling shows that Brown probably would lose in a runoff to Cameron, whereas Clegg has a decent chance to defeat Cameron. Then you want to insincerely top-rank Clegg, so that you can try to get your second choice instead of your third. That is, getting Clegg is better than helping Brown make it to the next round, only to be defeated by Cameron.

With Approval Voting, you never have to “betray” your favorite candidate like this. If you don’t think Brown has a chance, you are free to vote for Clegg to try to make sure you at least get someone you like better than Cameron. But you can STILL vote for Brown with no fear — and if enough voters (approximately 50%+) prefer Brown to the other two candidates, then Brown can still win, even if people thought he had no chance. In other words, being seen as “unelectable” doesn’t become a self-fulfilling prophecy with Score/Approval Voting.

Here are lots of other reasons it’s MUCH better than Alternative Vote.

http://ScoreVoting.net/CFERlet.html

Thanks for spotting that Helen – it’s now been corrected.

There are many myths about proportional representation leading to weak government, bac kroom deals, instability etc. Most of these are rebutted on the site of the Electoral Reform Society and I’m surprised you didn’t furnish a link: http://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/

You neglect to state the greatest benefit of the single transferrable vote system: your vote always counts. The voting system in the UK today is utterly iniquitous and it doesn’t deliver “strong govt” — which actually is taken to mean the ability to ram unpopular policies down the throats of the nation whether they like them or not. It has led to some spectacularly stupid and bad decisions (poll tax e.g.) which would just never have happened under coalition governments.

Your description of AV+ is inaccurate in one respect: “Candidates are elected in the order the party has listed them”.

As proposed by the Jenkins commission, a voter’s second vote can be either for a party or an individual candidate. If a party has won one or more top-up seats, its candidate(s) are elected in the order determined by the voters who expressed a preference. The party does not get to list an order.

This is very important – many electoral campaigners vehemently oppose party lists, so you shouldn’t be misrepresenting a system like that.

Great post – I just think you need to relabel the top bar in the graph? It says 2010 seat share, but I think you mean vote share.