Tony Hockley argues that the Conservative Party manifesto pledges for health and social care offer a sensible approach to NHS funding.

Tony Hockley argues that the Conservative Party manifesto pledges for health and social care offer a sensible approach to NHS funding.

One of the most telling ad-lib comments by the Prime Minister at the Conservative manifesto launch was his claim that NHS spending increases would be done: ‘in a sensible way’. For all the heat in current politics, the Conservatives have produced a shockingly sensible manifesto. The attacks around ‘trust’ have clearly hit home with the party, and they have very evidently learnt from Labour’s attack on their 2017 proposals for social care funding that they cannot face that huge challenge alone.

Just hours before the Conservative launch, the Labour Party added a new £58bn commitment on pensions, on top of their £83bn manifesto spending plans. The scene was set for an incredible tax-and-spend battle between the two parties and an extraordinary leap of faith behind the growth of the British state. The ‘sensible’ approach declared by the Conservatives came as something of a surprise just as people prepare to post their votes. This surprise was reflected in the questions at the launch. There was a general theme in the questioning of ‘Are you sure about this? Do you realise the scale of the gap between your promises and Corbyn’s?’.

Yet a sensible, ‘steady as you go’ approach is exactly what the NHS has always needed, but always been denied. Since 1982, Nick Bosanquet has been making the case to policymakers that growth of around 2% a year is needed to keep pace with demographic and technical change. Much more than this and inefficiency, inflation, and waste creep into the system. Inflationary costs from boom years (particularly on the NHS pension and new infrastructure) are carried well into the years of bust. Much less and the pressures for a sudden crisis investment become inevitable. The ‘weaponisation’ of the NHS at almost every election since 1950 has kept the NHS on this costly boom-bust cycle. Protecting this national treatment service from public sector cuts since 2008 has meant that sickness has been supported and health neglected. Even before this, Britain’s health system already ranked close to the bottom of the Commonwealth Fund’s global league table for achieving ‘health care outcomes’.

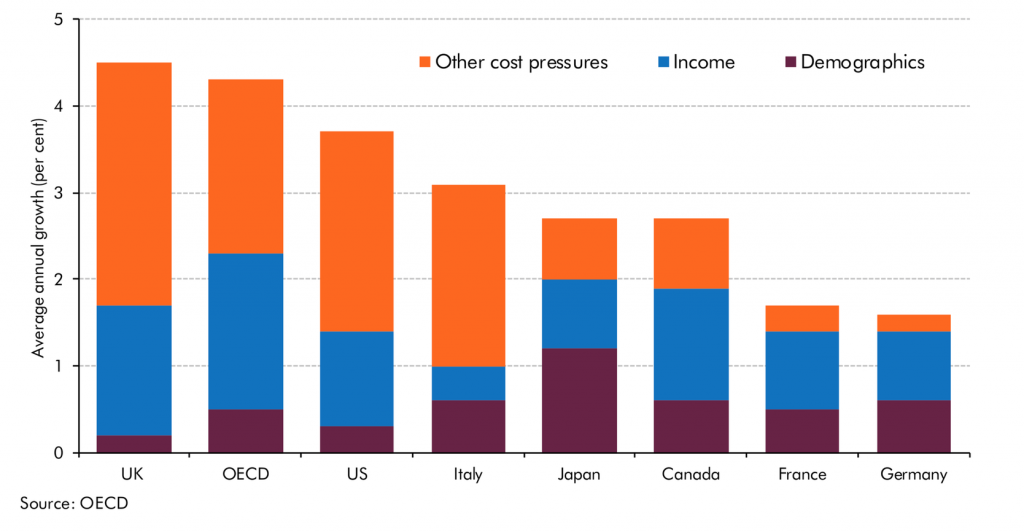

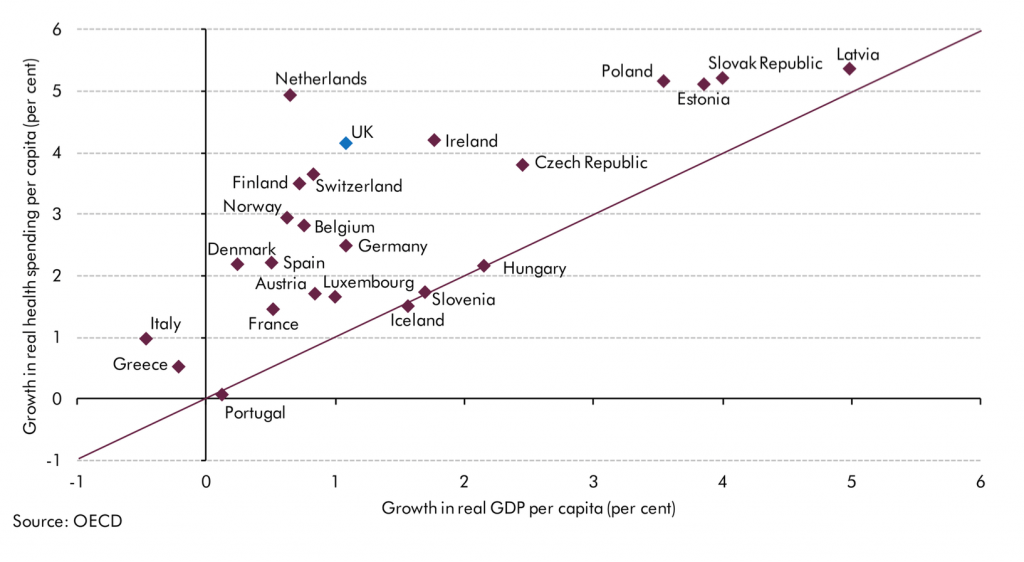

A steady approach to long-term NHS funding should create the first real opportunity to tackle some of the major determinants of health in a sustained way: disposable incomes, education, housing, the environment, and social services. Stabilising NHS spending growth, and maintaining it at levels that are normal for other European health systems may actually offer the first chance to tackle systematically the determinants since the NHS was created. These three charts from analysis by the Office for Budget Responsibility show the unique British problem in health funding:

Figure 1: Growth in public health spending per capita (1995-2009)

Figure 2: Growth of real health spending and GDP per capita (2000-2015)

What then of the specific commitments that are in the Conservative 2019 manifesto? Some of them are certainly worthy, but certainly not headline news for an election; improvements to hospital discharge systems for people with learning disabilities and autism is one example, and the extension of the Cancer Drugs Fund to cover treatments for auto-immune disease and paediatric rare disease is another.

The policy that probably most typifies the difference between the main parties is on car parking at NHS hospitals. NHS providers have a long history of trying to find ways to extract money from patients, and policymakers have long had to limit these once they are over-exploited. Once it was payphones and televisions, now it is car parking. As with many giveaways, however, a free-for-all policy hits hard capacity constraints. Many hospital car parks are already full, despite high charges. This problem gets worse, and the need to invest capital into car parks more demanding, when parking is free. As with dental checks, the Conservatives have chosen to target help on those most in need, rather than hit the capacity constraints and infrastructure costs of a new, universal commitment.

Thankfully, the Conservatives have learnt from their 2017 election problems on social care and avoided launching a ‘big idea’ on funding. Far better to try once again to work towards a cross-party solution, whilst continuing to reverse cuts to the current system. For social care cross-party agreement is the only way any reform would be likely to survive the subsequent election. A mutually acceptable solution must be found. This will be one that neither massively extends the role of the state nor massively subsidises inheritance, and which improves both the quality and quantity of social care. In the current political environment, it may be that this is best done by a small group of the ‘brightest and best’ from the various parties rather than through a formal inter-party committee. In the end, the solution will be 50% political and 50% technocratic.

Much has been made of the commitments on capital investment into hospitals, and the headline promises much debated: how many new hospitals? But the policies of most significance are those designed to tackle the workforce crisis. The abject managerial neglect of nursing in the NHS goes back more than a decade, as seen in the inquiries into the Mid-Staffordshire scandal. The demoralisation and comparatively poor treatment of the nursing workforce will be hard to repair: the fix being found to protect doctors from the impact of tax law on their large pensions cannot help in this regard. The manifesto provides some specific measures – the restoration of the bursary for students nurses, for example, and an NHS Visa to support global recruitment (again), and a vague commitment to ‘more supportive hospital management’. Over the next few years, the achievement of these changes will probably matter more for the quality of NHS care than anything else.

The promises are certainly conservative. At the start of this election the NHS establishment demanded an end to treatment of the health service as a political football. Ironically, Boris Johnson appears to have followed this advice, only to be kicked for not producing rabbits out of hats. Such is the stuff of British health policy.

________________

Tony Hockley is Director of the Policy Analysis Centre, and a Visiting Senior Fellow in the Department of Social Policy at the LSE, where he teaches Behavioural Public Policy. He is also a former Special Adviser in the Department of Health.

Tony Hockley is Director of the Policy Analysis Centre, and a Visiting Senior Fellow in the Department of Social Policy at the LSE, where he teaches Behavioural Public Policy. He is also a former Special Adviser in the Department of Health.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay/Public Domain.