While it is sometimes compared to a federal superstate, the European Union is different from most federations in that it contains an exit clause: Article 50. But how did Article 50 come to be? Based on a new study, Martijn Huysmans provides a theoretical and empirical account of its origins in the 2002-03 Convention on the Future of Europe.

While it is sometimes compared to a federal superstate, the European Union is different from most federations in that it contains an exit clause: Article 50. But how did Article 50 come to be? Based on a new study, Martijn Huysmans provides a theoretical and empirical account of its origins in the 2002-03 Convention on the Future of Europe.

The EU first adopted an exit right during the 2002-03 Convention on the Future of Europe. The clause came into force with the Treaty of Lisbon as Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union. On 29 March 2017, the United Kingdom triggered Article 50 and set in motion the process of its withdrawal from the EU. Clearly, Article 50 matters.

In a new study, I demonstrate empirically that an ‘exit-voice’ logic lies at the origin of Article 50. As a protection against undesired policy changes post entry, countries of the 2004 Eastern accession demanded an exit right. Underlying this fear of policy change was their much lower level of economic development and corresponding differences in policy preferences. As a mirror image, rich outliers like the UK and Denmark also supported Article 50, which likely contributed to its final adoption through the Treaty of Lisbon.

The Council gridlock interval

The theoretical argument outlined above leads to the conclusion that support for an exit clause will be strongest for countries that stand to lose from majority-approved legislative programmes. In the context of the EU, one key hurdle that legislation needs to pass is obtaining a qualified majority in the Council. After the Eastern enlargement, a qualified majority in the Council required 88 out of 124 votes.

This threshold can be used to calculate a so called ‘Council gridlock interval’ that indicates which states stand a greater chance of losing out from a qualified majority vote. Imagine that all states are placed along a line representing their ideal policies for a given issue. If we start at the left of this line and count up the votes until we reach the state that holds the 88th vote in the Council, then any state to the right of this point could potentially lose out in a qualified majority vote. Similarly, if we start at the right and count 88 votes in the opposite direction, then any state to the left of this line could also stand to lose out. But all of the states in the middle, who are neither 88 votes from the extreme left or right of the scale, should in principle never be compelled to accept a qualified majority vote they disagree with. These ‘core’ states are the ones located in the Council gridlock interval.

The countries of the 2004 Eastern accession were on average much poorer than the existing EU-15. To investigate the importance of heterogeneity along this dimension, each delegate at the Convention was associated with the 2003 per capita GDP of its country. The pivotal countries in the Council were Portugal at €13,994 per capita and Belgium at €27,293 per capita.

All of the Eastern accession countries except for Cyprus had a level of GDP per capita below the gridlock interval, while none of the EU-15 did. This means that the EU-15 together with Cyprus had a qualified majority to adopt policies that would be more favourable to member states with higher levels of economic development.

Predicting delegates’ positions on the draft of Article 50

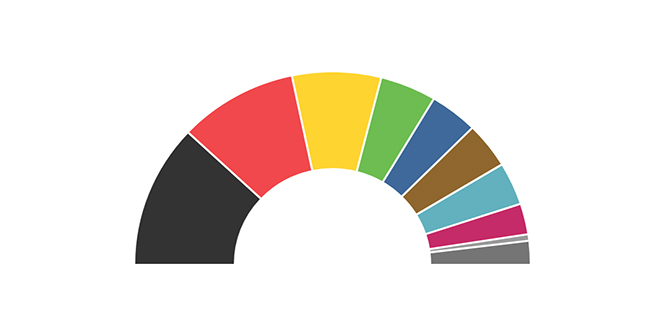

The figure below shows the predicted probabilities of Convention delegates being in favour of a free exit right, based on a regression controlling for country population and being an ex-Soviet country (the Baltic countries, having just escaped the Soviet Union, were especially apprehensive about joining a union from which you could not leave). The x-axis shows the level of anti-EU ideology of delegates’ parties. The bottom line shows that countries with a level of GDP in the gridlock interval were much less likely to be in favour of a free exit right.

Figure: Predicted probability of a member state being in favour of a ‘free exit right’ from the European Union

Note: The horizontal axis represents the level of anti-EU ideology expressed by a delegate’s party. The more anti-EU this ideology was, the more likely they were to support including an exit right from the EU (shown in the vertical axis). However, states are also distributed into three groups based on whether they were in the Council gridlock interval when arranged by GDP per capita. As can be shown with the “GDP core” states, those states within the gridlock interval were much less likely to be in favour of a free exit right. The states in each category are as follows: GDP Peripheral poorer (Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Estonia, Hungary, Czech Republic, Malta, Slovenia); GDP Core (Portugal, Greece, Cyprus, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Belgium); GDP Peripheral richer (Austria, Finland, United Kingdom, Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Ireland, Luxembourg). For more information see the author’s accompanying study.

In the main regression, the expected effect of being from a country with a level of GDP per capita below the gridlock interval is a 54-percentage point increase in the probability of being in favour of a free exit right. For delegates from countries above the gridlock interval, i.e. those in the rich periphery of the EU-25, which includes the UK and Denmark, the corresponding increase is 46 percentage points. Unsurprisingly, the regressions also show that the stronger the anti-EU ideology of a delegate’s party, the stronger the desire for a free exit right.

Conclusion

By including an exit right at the constitutional stage, political unions can ex-ante insure prospective members against undesired policy changes. The EU adopted a free exit right during the 2002-03 Convention on the Future of Europe. The resulting draft Constitution was not ratified, but through the 2007 Treaty of Lisbon the withdrawal clause containing the free exit right was adopted as the now (in)famous Article 50. So paradoxically (or not, depending on your intuition), the Article allowing unilateral exit has its origins in EU enlargement.

_________________________________

Note: the above was first published on LSE EUROPP – European Politics and Policy. It draws on the author’s published work in European Union Politics.

About the author

Martijn Huysmans is an Assistant Professor in the School of Economics at Utrecht University, where he conducts research on the Political Economy of the EU and teaches in the PPE program. He obtained his PhD in Applied Economics at the University of Leuven. Martijn is on Twitter @MartijnHuysmans.

Martijn Huysmans is an Assistant Professor in the School of Economics at Utrecht University, where he conducts research on the Political Economy of the EU and teaches in the PPE program. He obtained his PhD in Applied Economics at the University of Leuven. Martijn is on Twitter @MartijnHuysmans.

Featured image credit: Jay Allen / Number 10 (Crown Copyright)

The idea was to allow the poorer nations have a way out, it was never envisaged the second largest net contributor would pull up stumps and go.