Household debt levels have increased substantially in advanced nations over the past few decades and the UK is no exception. This rise is because of factors that have to do both with the supply of credit and the demand for credit. Basak Kus argues that any policy tool to tackle indebtedness must address both sides of the story.

Household debt levels have increased substantially in advanced nations over the past few decades and the UK is no exception. This rise is because of factors that have to do both with the supply of credit and the demand for credit. Basak Kus argues that any policy tool to tackle indebtedness must address both sides of the story.

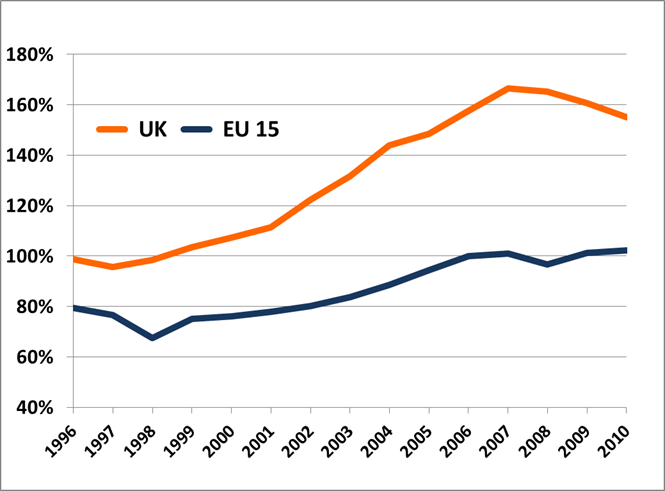

According to data from the European Credit Research Institute, as of 2010, UK households’ credit use on average amounted to 155% of their disposable income—significantly higher than the average of the EU-15. In fact, The Guardian recently reported that at £150bn a year, the UK has the largest credit market in Europe, and its size is expanding as we speak.

As staggering as these figures are, until recently scholars have paid very little attention to indebtedness as a socio-economic phenomenon. It is only with the economic crisis that the causes and implications of mounting levels of household indebtedness have begun to be examined systematically.

So what does the existing research tell us about household debt? This, for sure: in order to explain why debt levels have increased tremendously, and why they vary cross-nationally, we first have to understand the factors that shape the demand for and supply of credit.

Figure 1: Total credit to households as a percentage of disposable income

Source: European Credit Research Institute

The demand for credit

The rise of a consumer culture is often mentioned as a contributing factor. According to this view, the insatiable demand for consumer products has led households to save less and use more credit, fueling an increase in household indebtedness.

While there might be some truth to this, many scholars believe that this theory diverts policymakers from accepting and addressing the socioeconomic sources of credit reliance and rising indebtedness, such as shrinking wages and rising income inequality. Citizens at the lower end of the income distribution often find many of their basic needs unattainable without loans. Especially in liberal market economies, such as the UK and US, where the redistributive effort on the part of the state has not matched the increase in inequality, credit has become essential to maintaining the basic necessities of a middle-class lifestyle. In both of these countries, income inequality and household credit use have been increasing in lockstep since the early 1980s.

The supply of credit

The rules and regulations that determine who can lend, who can borrow, how much, and under what terms also matter a great deal in shaping household indebtedness. While some nations have more restrictive rules with regards to these issues, others make borrowing and lending relatively easy.

In the UK, the early 1970s constitute a turning point. In 1971, a Royal Commission chaired by Lord Crowther investigated the regulatory structure and status of credit use in the UK. The Committee subsequently issued a report arguing “that reform of the existing legal tangle is badly overdue, and that liberation of the consumer credit industry from the antiquated provisions, and from the official restrictions, that hobble it will enable it to make an increasing contribution to the efficiency of the national economy and to the standard of living of the public.” Increased access to credit, according to the report, would contribute to the citizens’ welfare in several ways: by bridging the gap between income and spending in the intervals between the receipt of income; by facilitating household budgeting over time; and by enabling the purchase real and financial assets in excess of the amounts permitted by households’ own savings.

The report criticised state intervention in the credit markets in the name of consumer protection and argued that it is the consumer choice that matters:

“Our general view is that the state should interfere as little as possible with the consumer’s freedom to use his knowledge of the consumer credit market to the best of his ability and according to his judgment of what constitutes his best interests. While it is understandable and proper for the state to be concerned about the things on which people spend their money and even to use persuasion to influence the scale of values implied by their expenditure patterns, it remains a basic tenet of a free society that people themselves must be the judge of what contributes to their material welfare.”

The goal of policy, the report went on to argue, must be to treat consumer credit users “as adults who are capable of managing their own financial affairs, and not to restrict their freedom of access to credit in order to protect the relatively small minority who get into difficulties.”

These ideas greatly influenced the 1974 Consumer Credit Act, where the UK made a decisive turn away from a more continental model of credit market regulation towards an American approach. The deregulation of credit markets in the following decades made a larger supply of credit available to a larger pool of people.

With less rigid regulations in the UK, the financial sector and credit markets have become more aggressive in pushing high-risk loans – particularly to citizens in the lower end of the income distribution.

Taken together, heightened insecurities, shrinking incomes, increased demand for consumer products, and increasingly aggressive credit markets are leaving citizens more and more indebted. Policy designed to tackle this must look not just at demand, but at the supply side too.

___

Note: This blog is based on the article “Sociology of Debt: States, Credit Markets, and Indebted Citizens”. It represents the views of the author and not those of the British Politics and Policy blog nor of the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

___

Basak Kus is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Wesleyan University in the US.

Basak Kus is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Wesleyan University in the US.

(Featured image credit: Eden, Janine & Jim CC BY 2.0)

Access to credit since the 1970’s has gradually influenced cultural & socioeconomic norms.

Since the “credit crunch” in 2007/8 there has been a protracted period of low or negative growth, which has had an adverse effect on productivity and job security in consumer driven markets.

The fall in growth & productivity, are impacting upon available provisions for health & social care programmes.

With low base rates for savers, negative returns from government bonds & increased competition for goods & services, whilst high cost lending takes up the gaps in money supply, there are many people simply unable or unwilling to save.

Reversal of such a pernicious trend, culturally, economically and morally will be extremely difficult.

I see this chart quite a lot now, usually used as evidence that households are on the verge of collapse. But am I right in thinking that it relates households’ liabilities – what they owe – to their incomes – what they earn. If so, it completely ignores their assets, which, I’d imagine, have grown (e.g. the housing market). Perhaps the same chart with the asset side of households’ balance sheets factored in could be added? For all we know household net debt could have shrunk across the period your chart covers (I don’t think it has, but we can’t know that from what we have here).