The UK has always had a contentious relationship with the European Union. John McCormick argues that this relationship has been hampered by popular misunderstandings, driven by a lack of credible information and general hostility towards European integration. He suggests that more attention should be paid to the positive aspects of EU membership and that academics should contribute more to public discussion on the UK’s future in the EU.

The UK has always had a contentious relationship with the European Union. John McCormick argues that this relationship has been hampered by popular misunderstandings, driven by a lack of credible information and general hostility towards European integration. He suggests that more attention should be paid to the positive aspects of EU membership and that academics should contribute more to public discussion on the UK’s future in the EU.

This article was originally published on the LSE’s EUROPP blog.

The British have long had their doubts about the European Union. They joined late and they had a referendum on membership within three years of joining. They have since dragged their feet on multiple EU policies (although, to be fair, they have provided important leadership on others) and they now face the prospect of a second referendum on membership. Small wonder, then, that the UK is regarded as the awkward partner in the European club.

But the recent debate in the UK about the EU has shown that while British citizens often hold strong opinions about their membership of the EU, those opinions are not always well informed. The biannual surveys run by Eurobarometer, the EU’s opinion polling service, make two key points about Britain: it is among the least enthused of all EU Member States (barely one-fifth of people in the UK currently have a positive view of the EU, placing them slightly above those in Spain, Cyprus and Greece) and it understands the EU much less than anyone else (barely one-third of Britons think they have a grip on how the EU works, one of the lowest rates in the EU).

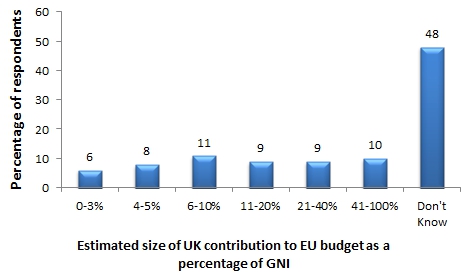

This unfortunate blend of hostility and confusion has spawned a public debate over the EU that is replete with myths and misconceptions. Consider just three of the most persistent European fables. First, we are often told that as much as 80 per cent of British law is now made in perfidious Brussels. The figure is closer to 7 per cent, according to a 2010 House of Commons Library report. Second, Britain is losing control to unelected European bureaucrats. This argument fails to recognise the extent to which decisions at the European level are controlled by national political leaders and the elected European Parliament. Third, membership of the EU is costly. In a 2009 poll, people’s average estimate of how much the UK contributes to the EU budget was 23 per cent of gross national income. The true figure was 0.2 per cent. The spread of estimates is shown in the Chart below.

Chart: British citizens’ estimates of the size of the UK’s net contribution to the EU budget as a percentage of GNI in 2009 (actual contribution was 0.2 per cent)

Source: Eurobarometer

The myths are perpetuated by Eurosceptic media (the Daily Mail and the Daily Express leading the way), by the remarkable ability of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) to attract a level of attention that is entirely out of proportion to the extent of its electoral support, and by the strange reticence of the pro-EU camp to speak up. We hear far more about what is wrong with the EU than about what is right with it, and the result is a public debate that is dangerously lopsided. With the prospect of a new referendum on membership looming, it is critical that the balance be changed. If the UK votes to leave the EU, it is better that it does so from a position of understanding than of misunderstanding.

Why Europe matters

My book Why Europe Matters is an attempt to focus attention on the benefits and the achievements of the EU, and an effort to inject some balance into the debate over Europe. It acknowledges the EU’s problems – no large network of institutions is perfect, the EU has made many mistakes and there are still considerable holes in its agenda (not least its modest progress in opening up markets in services) – but it is primarily interested in pointing out how much we have all benefitted from European integration. Its core arguments follow.

The debate about Europe can be fruitful only if we have a better understanding of the EU and the process of integration, unclouded by myth. Integration has helped mould Europe into a peaceful and peacemaking example in a world where too many retain an unhealthy fascination with military power. It was a deserving recipient of the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize. Europe abundantly illustrates the benefits of free trade and of carefully reducing the barriers to the free movement of people, money, goods and services.

Once the problems of the euro are resolved (and they will be), we will better appreciate the advantages of a single currency. It has benefits for consumers and for business, and offers the only viable alternative to the US dollar, whose global credibility is threatened by reckless US economic policies and a burgeoning national debt. In spite of what we are often told, there is majority support for integration among Europeans, and there are numerous channels through which their interests are represented and protected. While democracy is messy and imperfect, talk of a European-level democratic deficit is exaggerated.

There is a community of Europe that is easier to define than most people believe, and Europeans have much more in common than most of them realise. The European political model has encouraged compromise, consensus, higher standards and improved protection, and it is an effective means to the resolution of shared problems. The EU stands as an exemplar of a global player that uses inclusive and soft tools to achieve its policy objectives. We do not need more or less Europe so much as an improved Europe, meaning that we need to build on those areas where integration works, repair those where it does not, fill in the gaps and make sure that Europe is better understood.

The debate over Europe has not only become lopsided. It has also become remarkably bad-tempered. A pro-European, I am active on social media, where I routinely face abuse from critics of the EU. I was charged not long ago of being a traitor to Britain, and I have been accused of being in the pay of the EU. Doubtless there is anger in the other direction, and, indeed, the rise of anonymous internet trolls has seen the rise of incivility in public debate more generally. But if we are to have a productive debate about the EU, we need to deal with verifiable facts rather than myth, we need to ensure better understanding of how the EU works and what effect it has had, and we need to hear from all sides.

Academics have a particularly important role to play in this regard. They produce enormous amounts of valuable information and analysis, but most of it is directed at their peers rather than the wider public. It is time that they engaged more actively in the debate over the European Union, in order to help correct the misconceptions and inject balance into that debate before it is too late.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting.

_________________________________

John McCormick – Indiana University, Indianapolis

John McCormick – Indiana University, Indianapolis

John McCormick is Jean Monnet Professor European Union Politics at the Indianapolis campus of Indiana University in the USA. He has published widely on the politics and politics of the EU, comparative politics, British politics and environmental policy. His textbook Understanding the European Union (Palgrave Macmillan) will shortly be published in a sixth edition.

The British nations and peoples have a long history of losing and regaining sovereignty extending as far back as the Pagan Roman occupation. Later British migrants to North America experimented with differents forms of government, ranging from colonialism to republicanism for the States, yet the union has put states’ sovereignty second to that of an ever-growing federal government. The countries of Europe face a similiar future as a result of union – each country will become a mere state with subsequent loss of sovereignty in the new United States of Europe.

New and additional layers of bureaucracy will serve as camouflage in the USE to help reduce sunshine on corporatist and other statist machinations, whilst negatively impacting upon democracy. Growing numbers of British voters today sense that EU membership means loss of sovereignty and that historially this has never bode well. The continentals were always the chief threat to a free society. This sentiment no doubt accounts for UKIP’s recent surge in growth as a political party.