The government is suggesting that councils had implemented inappropriate parking charges that undermined the vitality of high streets, flying in the face of the available evidence. Richard Berry argues that regardless of the party in government, Whitehall has long had a propensity to blame local authorities for wider policy failures. This trend appears now to have intensified.

The government is suggesting that councils had implemented inappropriate parking charges that undermined the vitality of high streets, flying in the face of the available evidence. Richard Berry argues that regardless of the party in government, Whitehall has long had a propensity to blame local authorities for wider policy failures. This trend appears now to have intensified.

While some motorists might be annoyed at the Department for Transport’s recent introduction of on-the-spot fines for tailgating and middle-lane hogging, at least they know that the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) is on their side. Indeed, Secretary of State Eric Pickles has spent much of the summer expounding on the woes of those in need of a cheap place to park their car.

The summer campaign

First, in late July, proposals were floated to allow drivers a 15-minute ‘grace period’ when parking on double yellow lines. Soon after that, Eric Pickles reacted to the news that local authorities were forecasting a national surplus of annual £635 million from their parking operations, as revenue from charges and fines exceeds expenditure. This was deemed ‘profit’ by Pickles, who said there was a need to ‘rein in unfair town hall parking rules’.

Next came the battle of the driveways. Responding to a growing trend in which people use online services to rent out their driveways as parking spaces, some councils have been requiring homeowners to apply for planning permission, so as to reflect the change in use of their property from solely residential to commercial. Pickles took issue with this in early August, announcing that he was going to publish new guidance making it clear that planning permission is not needed to rent a single parking space. ‘This government is standing up against the town hall parking bullies and over-zealous parking enforcement’, he said, describing planning application fees as a ‘driveway tax’. Thus, residential parking became yet another issue – just like the conversion of offices to flats – where central government has decided to constrain the planning powers of councils on what should be a purely local concern.

The most recent move in the campaign came in late August, when DCLG announced even more planning guidance, instructing councils to remove any unnecessary street clutter such as signage, bollards and road humps, in order to free up additional parking space. The declared rationale for these changes – as it had been with the ‘grace period’ idea earlier in the summer – was to boost local high street businesses by encouraging motorists to visit them. At this time Pickles also had another dig over parking charges, suggesting that councils had implemented inappropriate charges that undermined the vitality of high streets.

Evidence on high street performance

In the latest announcement, the government cited new research from the British Parking Association (BPA) and Association of Town and City Management (ATCM) to support its case that high parking charges and limited capacity negatively affect high street trade. The DCLG press release states explicitly that the research shows ‘there is a strong relationship between parking provision and high street footfall’. However, the report itself does not make this claim. In fact, on parking capacity the report states that the evidence presented ‘by no means implies there is a relationship between the quantity of car parking spaces and footfall’. Similarly, on charges, the report states that the findings ‘do not conclusively demonstrate that parking tariffs are influencing [high street] decline across the UK’.

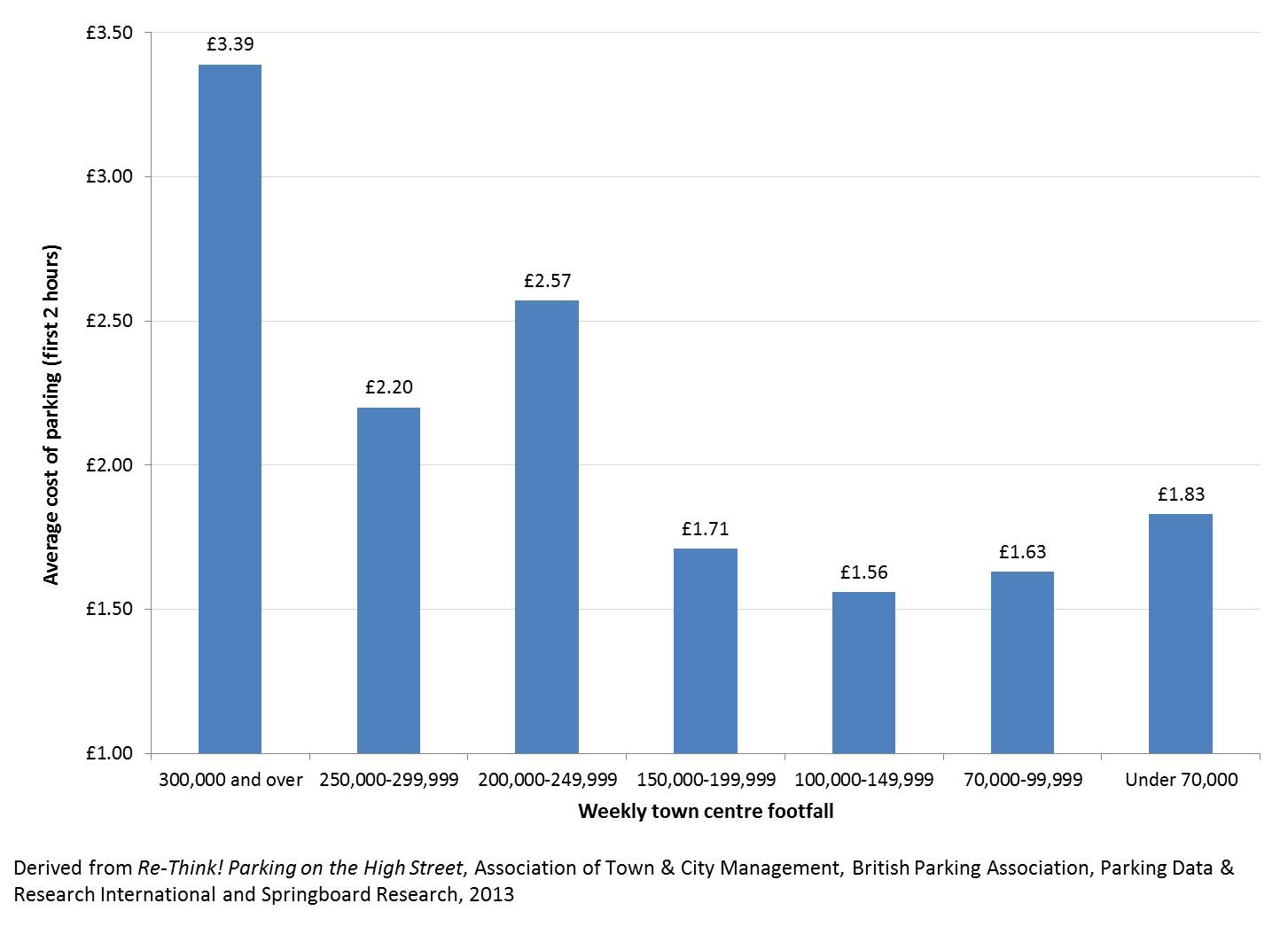

The sole piece of detailed evidence from the BPA/ATCM report quoted in the DCLG release is this rather confusing sentence, a direct quote from the report: ‘The mid-range and smaller groupings of centres that charge more than the national average in accordance with their offer, suffered a higher than average decline in footfall for 2011’. The report’s authors have divided 99 town centres into categories, or ‘groupings’, based on their level of footfall. The average parking tariff within each grouping is shown to correlate positively with footfall – more popular town centres have higher charges. But then the authors identify that a couple of the groupings appear to have disproportionately high charges (see the chart below), given their level of footfall. Then they look at the recent drop in footfall across all town centres, and find that those groupings with relatively high charges have suffered steeper-than-average drops.

Chart: Town centre footfall and cost of car parking, 2011

Unfortunately, this finding is the result of a convoluted, debatable and possibly misleading interpretation of partial data. The sample sizes in the ‘groupings of town centres’ are very small, and there is no suggestion that each groupings contains a similar range of types of centre. The differences in average parking tariffs between the groupings are so tiny they are inconsequential – in some cases the difference is a few pennies. The report also appears to contain a blatant error – the category described as ‘mid-range town centres’ is not consistent throughout the report – which undermines the government’s key evidence claim.

The government’s announcement makes no reference to competing sources of evidence. In particular, London Councils commissioned a review last year of academic and other literature on the link between parking capacity and pricing, and town centre performance, finding no substantial evidence of a relationship.

DCLG might also have referred to evidence the many other factors that influence the success of local high streets, some of which can be directly affected by central government. Firstly, there are the tax loopholes that allow online retailers such as Amazon undercut prices on offer in high street shops. Then there is the growth of large, out-of-town retail development, left largely unchecked by all recent governments. Furthermore, a lack of diversity brought about by the removal of controls on businesses like betting shops. Perhaps most importantly, the sluggish performance of the economy has ensured consumer demand continues to be constrained.

Local control

Regardless of the party in government, Whitehall has long had a propensity to blame local authorities for wider policy failures. This trend appears now to have intensified. It is clear the coalition would love to be in a position to reduce taxes, but the state of the public finances makes this near-impossible. Attention is therefore being directed onto councils, who are accused of imposing unwarranted taxes and charges against the will of government. Pickles’ criticism of council profiteering reveals the double standard: as Simon Jenkins pointed out in The Guardian, when the Treasury generates a surplus in central government finances we are expected to interpret this as a sign of fiscal health, but when local authorities manage the same feat it can only be because they are ripping off the public. The apparent failure of the government’s flagship policy initiative on high streets, the Portas Pilots, discussed in Parliament this week, creates further incentive to blame-shift.

None of this is an argument for or against parking charges, grace periods, driveway taxes, or street clutter. Certainly, some councils seem to accept there is a link between charging and the local economy; for instance, Croydon has recently introduced 30 minutes’ free parking in town centre locations for this reason. The key point is that on the government’s own localism commitments the appropriate level at which to decide these things should be locally, where councils can weigh up the cost and convenience of parking against the many other influences on local economic performance. If people truly feel their council is not sufficiently supportive of motorists they can lobby councillors and, ultimately, vote for a change at the next election. Micro-focused central government interventions only serve to make those votes a little less meaningful.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Richard Berry is Managing Editor of Democratic Audit. His background is in public policy and political research, particularly in relation to health and local government. In previous roles he has worked for the London Assembly, JMC Partners and Ann Coffey MP. Richard is also the founder of the public policy blog Modest Proposals. He tweets at @richard3berry.