There was an air of confidence at the Green Party annual conference last weekend, with keynote speeches painting a clear target on Labour. James Dennison argues that, though the Green Party is likely to see its vote share increase over the next few years, it neither has the anti-elite credentials nor the untapped demographic to enjoy the successes of UKIP.

There was an air of confidence at the Green Party annual conference last weekend, with keynote speeches painting a clear target on Labour. James Dennison argues that, though the Green Party is likely to see its vote share increase over the next few years, it neither has the anti-elite credentials nor the untapped demographic to enjoy the successes of UKIP.

With attention on the knife-edge Scottish independence referendum, the annual Green Party conference last weekend still managed to get surprisingly widespread coverage, with commentators keen to depict the Party as the next insurgent force in British politics – a ‘UKIP of the left’. Indeed, the two keynote speeches laid out a series of left-wing policies with relatively little focus on environmentalism. But left-wing policies are nothing new in the Green Party and focusing on them, instead of green policies, is a logical strategy given their electoral aims.

Media reports are right to interpret the Green Party’s conference strategy as an attempt to hurt Labour. Both the speeches of Party leader Natalie Bennett and Caroline Lucas, former leader and the only Green MP, included long lists of what they see as failings of the Labour Party. Lucas lambasted Ed Balls, the shadow chancellor, for signing up to the coalition’s austerity plans and welfare reforms and highlighted the Labour Party’s openness to fracking, Trident, marketisation of the NHS and its abstention on the Justice and Security Bill and Immigration Bill. Bennett went through Labour’s front bench one-by-one to point out their compromising attitude to the coalition, notably highlighting shadow Work and Pensions Secretary Rachel Reeve’s promise to be tougher on welfare than the Tories. She then focused on what the Greens would do, effectively giving a list of ‘Old Labour’ priorities – renationalising the railways, community-run comprehensive schools, a mandatory living wage and a revival of social housing.

However, contrary to the argument of the Independent that proposing social justice policies represent a ‘change of hue’ and an ‘electoral calculation’, the Green Party has long been on the far left. Their manifesto shows long-standing commitments to leaving NATO, the gradual removal of immigration controls, introducing a maximum wage and repealing anti-trade union legislation. The Party has been committed to renationalising the railways since at least 2004 and has supported all of the major strikes of the last 20 years while attempting to build up links with the Trade Union movement. Indeed, the Green Party of England and Wales has repeatedly been labelled as the most left wing green party in Europe. The almost exclusive emphasis on social justice in this weekend’s speeches may have been new but, unlike what is claimed by several journalists, the content was not.

The decision to focus on Labour’s shortcomings may appear surprising given that the demographic of the Greens’ traditional support – southern, non-unionised, middle class, ‘post-material’ and well educated – makes the Liberal Democrats the natural competitor of the Greens. However, Westminster electoral competition has sharpened the mind of the Green Party. The roll-call of recent Green successes in Lucas’s and Bennett’s speeches – increased membership, polling at the same level as the Lib Dems, one more MEP in 2014 – are all secondary in comparison to the Green Party’s toughest and most important challenge, maintaining their one Westminster MP in the Labour-Green marginal seat of Brighton. Any incumbency advantage that the Greens may have in 2015 will be offset by a mixed record while in control of Brighton council and a resurgent Labour Party. The highest Green polling in any other seat only puts their support around 20 per cent, making Brighton their only realistic chance of success, notwithstanding the ambitious target of 3 or more seats as heard this weekend. The Greens will focus all of their resources, rhetoric and activists on defeating Labour in their Brighton stronghold.

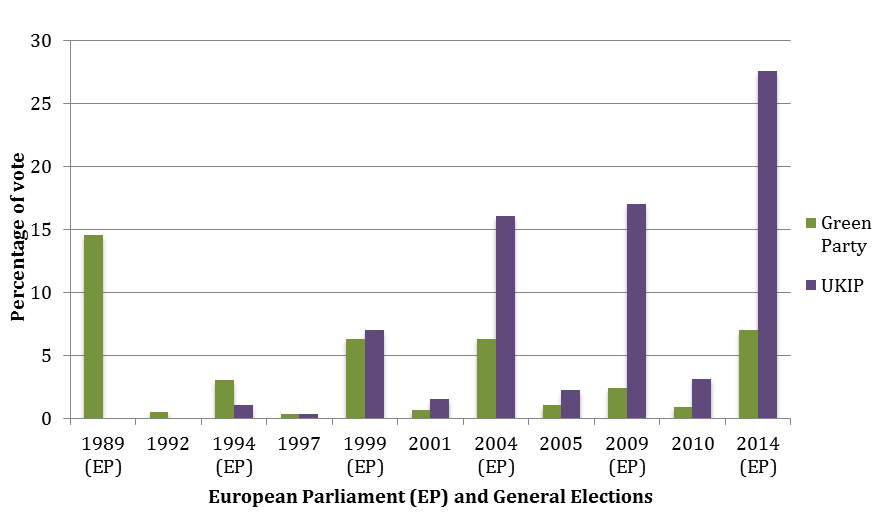

The other major claim featured in the media is that the Green Party has the potential to be a similarly insurgent and anti-elite ‘UKIP of the left’. The history of the Green Party’s electoral success, shown below, goes someway to explain why I am sceptical about this possibility.

Figure 1: Green Party and UKIP vote share since 1989

Whereas UKIP have received a continuous increase in support, the Green vote share has been more erratic. In the 1989 European elections, the Green Party came from nowhere to claim third place and 15 per cent of the vote. John Curtice argued that this success resulted from a combination of protest voting, a common theme in European elections in an age of reduced party allegiances, and a ‘Green Tide’ that swept over Europe following post-Chernobyl alarm about environmental degradation, which was exploited in the party’s purely ecological and widely acclaimed party political broadcasts. The Greens’ particularly large vote share in the UK that year was also caused by the remarkable collapse of the SDP-Liberal Alliance, the Liberal Democrats’ predecessors. Their success encouraged Labour and the Conservatives to incorporate environmentalism into their policies and rhetoric, robbing the Greens of their previous monopoly over ecological matters. Moreover, through the 1990s the Liberal Democrats regrouped to become, with the nationalist parties, the natural protest vote in the West Country, Wales and Scotland, a role later played by UKIP in the south and east of England. Such developments forced the Greens to form policies on non-environmental issues and find a political home to the left of the major parties, depriving them of the opportunity to again be the catch-all protest party they were in 1989.

In 2015 the Greens will be important, not because they can be a ‘UKIP of the left’, but because even a slight swing in their favour could rob Labour and the Liberal Democrats of seats. This prospect has encouraged both parties to recently champion environmental policies. In time for the Green Party conference, Labour made a number of attacks on the coalition’s green record, which they argue has seen an ‘unprecedented’ environmental decline. The Liberal Democrats also used the week to propose a series of green laws. The three major parties are able to undermine the Green Party vote by adopting the latter’s policies, a tactic they are less able to use against UKIP. First, UKIP actually has very few policies and, second, the few policies that they do have, anti-immigration and withdrawal from the European Union, are still considered extreme. Finally, UKIP’s platform is aimed against the established parties themselves. As such, UKIP have a near monopoly on some very popular policies while the Greens must operate in a more competitive marketplace.

Moreover, unlike UKIP, the Green Party will find it difficult to move beyond anything other than a ‘soft’ anti-elitism. Natalie Bennett did say this weekend that UKIP are correct to argue that ‘the political class does not look like, sound like or have the life experiences of most people in Britain.’ However, anti-elite oratory poses the risk of discouraging support from the Greens’ well-educated, middle class base of voters, who are traditionally the least responsive to us-and-them divisions, which Albertazzi and McDonnell argue is the hallmark of populism. Furthermore, the idea of a ‘virtuous, pure people’ exploited by a malevolent elite is harder to espouse once a clear, and necessarily divisive, position is taken on the left-right spectrum. It is even harder when this position includes fewer immigration controls, an issue which consistently polls as the most important for the British public. Finally, simple anti-elite rhetoric will be challenging to combine with a full slate of policies. As Bennett says herself, ‘It’s partly because Ukip has a very simple message that is easy to fit into a tabloid headline or a tabloid sentence. In the Green Party we understand the world is a lot more complicated.’

Overall, the Green Party may gain support because of the on-going de-alignment of party allegiances and a probable decline in Liberal Democrat support but it is unlikely to ever enjoy UKIP’s current popularity. The adoption of environmental policies by most political parties forced the Greens to become a party of the far left in the 1990s, a position neither vacuous nor popular enough to gain widespread support. Focusing on taking votes from Labour has nothing to do with a move to the left but is instead a result of electoral imperatives in their only Westminster seat. There is little chance of the Green Party reaching even half of UKIP’s poll ratings but they can take solace in continuing to force other parties to improve their green credentials and may end 2015 with just as many MPs as Nigel Farage’s party.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: Dulcie Lee CC BY 2.0

James Dennison is a PhD researcher at the European University Institute. He has previously worked at the Houses of Parliament and completed an MSc in Political Science and Political Economy at the LSE.

James Dennison is a PhD researcher at the European University Institute. He has previously worked at the Houses of Parliament and completed an MSc in Political Science and Political Economy at the LSE.

Does the LSE blog just post anything now? What a bizarre and narrow-minded way to position the argument. Would the author like them to be the UKIP of the left? What is the relevance?

Today’s Guardian ICM poll has the Greens on 7% and Ukip on 9%. The 2% difference is within the polling margin for error and suggests a much closer parallel between the left and right resurgences.

I like the Conversation website where contributers state their affiliations and potential conflicts of interest. So James, what are yours. Which Party did you work for in Westminster if any? Are you a member of any political organisation. Totally fine if you are, its not a criticism; I just think writers on this sort of subject should declare their interests.

“There is little chance of the Green Party reaching even half of UKIP’s poll ratings” … Err. The Greens are at 6.5% in the latest Indy “poll of polls” from John Curtice, and UKIP is only on 14-15%. They’re already at half of UKIP’s general election support. This article also relies too heavily on the “traditional Green support” argument. It doesn’t explain the recent surge in Liverpool and Solihull (where, on both councils, the Greens now form the biggest opposition party).

Well it is hardly surprising the green party are not making headway they have based their entire manifesto on a single issue based on a proven lie. Ukip on the other hand have many policies throughout the spectrum of peoples lives such as being the only party to truly be anti privatisation of the NHS which is what will happen when the TTIP is forced on to us and the conlablibdum and green party agree with it happening.

By ‘proven lie’, I assume you mean global warming, which 97% of climate scientists agree is happening?

I’m sorry if you’re referring to something else, but Green policy is fairly wide-ranging, and that’s the closest to a ‘single issue’ that I can imagine you mean.

Meanwhile in the real world, Green policy is actively against TTIP, whereas despite it seeming ideally designed for them, UKIP haven’t came out against it. The closest I can find to an official statement is an opinion piece by a UKIP Parliamentary canddiate in favour of it (http://www.ukipdaily.com/ukip-welcome-proposed-free-trade-agreement-european-union-us/#.VBW-7xbDWGw)

So ‘the Green Party has long been on the far left’ – really, the FAR left? Do you really want to argue that? You further claim that ‘…the Green Party of England and Wales has repeatedly been labelled as the most left wing green party in Europe.’ Apart from the one article you refer to on the site of the Left Unity party, is there any evidence the Green Party has ‘repeatedly’ been described in this way and, more importantly, that this claim is justified?

Rather negative article against the Green Party which I also believe to be rather inaccurate as two of your main points in this blog are false. 1. UKIP are not anti elitist (you mentioned yourself that UKIP only have two policies, neither of which are related to social justice). 2. You’ve based your election predictions on a poll which takes into account a mere 5 constituency areas. Their best chance of a second seat, behind Brighton, is Bristol West (not included in Ashcroft Polls).