Libby Hackett argues that we need to increase the capacity for higher education places in future years if we are to grow our economy and ensure a bright future for more young people.

Libby Hackett argues that we need to increase the capacity for higher education places in future years if we are to grow our economy and ensure a bright future for more young people.

Graduate employment regularly makes the headlines. All too often, the popular perception is that ‘there are too many graduates’ in the UK and that young people should question whether it is worth going to university. We need to look at the full story behind these headlines. The way government, universities and employers collectively choose to respond to this popular perception will have serious consequences for the future wellbeing of our economy and society. This is why we at University Alliance have explored the evidence and indicators that given an accurate portrait of labour market trends and what the implications are for us here in the UK.

Our report, The way we’ll work, shows there is a serious misconception at play here. The evidence in the report clearly shows the UK actually needs more graduates, not less. Contrary to popular belief, the labour market indicators we looked at suggest that there is a shortage of graduates in the UK. Technology is changing the way we work and it is also changing the structure of the labour market, resulting in an increased demand for graduate attributes. In light of these projections, the Coalition Government’s decision to cut around 25,000 university places for next year could seriously hold back our capacity for economic growth.

The report draws on the large body of evidence on the shape of labour markets in developed economies. It demonstrates that if the UK is to remain globally competitive, we need a greater proportion of graduates in our workforce. We also need to improve social mobility by creating genuine progression opportunities.

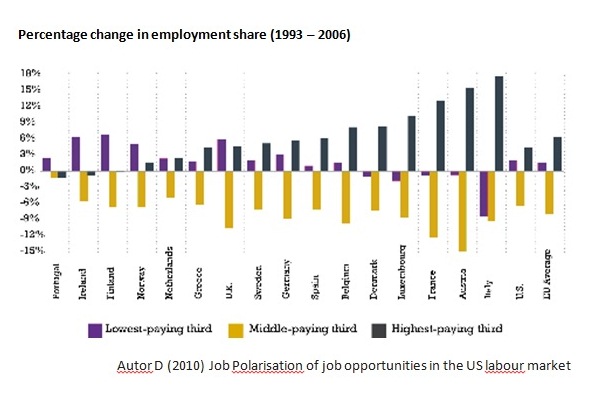

Since the early 1990s, several factors have led to the ‘hollowing out’ of the labour market in developed economies: sustained growth in high-wage, analytical, non-routine jobs; an expansion of manual, lower wage jobs; and a contraction of routine, middle wage jobs. Essentially, this created an ‘hourglass’ shaped labour market.

The graph below shows changes in employment share between 1993 and 2006 across 16 European countries and the US. It clearly demonstrates the dramatic reduction in middle-wage employment over that period across all 17 countries. The comparability of these changes across this group of developed nations indicates that there are common drivers contributing to the reduction in employment share of middle wage occupations.

The observed reduction in the employment share of middle wage jobs is linked to the substitution of technology for routine tasks, which is highly concentrated in occupations in the middle of the earnings distribution. Other factors also work together to increase the hourglass shape of the labour market, including globalisation, offshoring, shifts in consumer demand and changing national demographics.

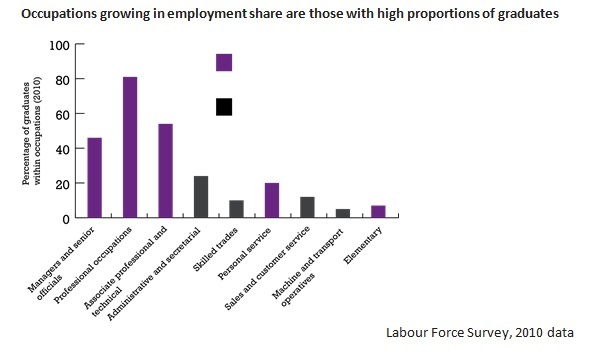

The strongest observed employment growth has been in the three occupation groups with the highest density of graduates, together accounting for three quarters of growth between 2000 and 2010 as demonstrated in the graph below.

In this graph we are looking at the percentage of graduates within each occupation group. The purple bars are the occupation groups that are forecast to have a growing employment share up to 2020. The occupations forecast to grow the most are the same three occupation groups that have grown most in the past two decades and that have the highest proportions of graduates – up to 80%.

The report looks at the implications of these changes on society and the economy and makes recommendations of how higher education policy could respond to meet the challenges and capitalise on the opportunities an hourglass shaped economy presents.

We argue that a rich and growing supply of graduates is needed to support an hourglass-shaped economy. The proportion of our working population at graduate-level will influence the nation’s productivity, pattern of economic growth and ability to meet the needs of business, individuals and the wider society.

As a country we also need to ensure that in an hourglass shaped economy there are effective progression routes through to high-level qualifications. Professional development is essential in order to tackle rising inequality and to ensure that people do not get trapped at the bottom of the employment market.

The UK economy is not presenting any of the four labour market signals we considered that might suggest there are too many graduates in the economy. Graduate vacancies continue to grow. Jobs in ‘graduate dense’ occupations are an increasing proportion of the total workforce. Graduate employment rates have been maintained despite the rapid expansion in the number of graduates. Added to all of this there is still a significant graduate premium.

Youth unemployment is at record levels while demand for going to university is high. Social mobility is at a standstill, yet we know that in our changing economy it is a university degree that creates more opportunities for people than anything else. Applying logic would see the total number of university places increased. However, they have been quietly cut by around 25,000 places compared with last year. Budgets may be limited but we should be stating the case for increasing the capacity for higher education places in future years if we are to grow our economy and ensure a bright future for more young people

Our global competitors are continuing to invest heavily in expanding higher education despite their own budget deficits. In contrast, England reduced the number of places available at university to control expenditure. To equip the population to find continuing opportunities in the labour market and to meet the growing need for graduate attributes, we must continue to seek ways to increase investment, public and private, in universities.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Libby Hackett is the Director of University Alliance – representing 23 universities at the heart of the higher education sector to Government, Whitehall and the media. Libby has extensive experience of working in the higher education policy environment. She joined University Alliance from The Russell Group of Universities where she was Director of Research and before that she had been a special advisor to the Parliamentary Select Committee for Education and Skills.

A very interesting read and I will share.

Do you think the decision to uncap the number of AAB and AAA students institutions can accept will make much difference?

I have heard that Bristol are indicating another 1000 first years in their September intake and I expect this trend will continue across other Russell Group universities.