Following the announcement of its mini-budget on 23 September, the government is gambling that tax cuts will lead to a sustained increase in the UK’s growth rate. But is this strategy likely to be successful? Nicholas Barr writes there is a wealth of evidence against tax cuts alone producing growth – and in the absence of this growth, the UK risks heading into a downward economic spiral.

Following the announcement of its mini-budget on 23 September, the government is gambling that tax cuts will lead to a sustained increase in the UK’s growth rate. But is this strategy likely to be successful? Nicholas Barr writes there is a wealth of evidence against tax cuts alone producing growth – and in the absence of this growth, the UK risks heading into a downward economic spiral.

In the face of high inflation, the government’s mini-budget on 23 September was concerned mainly with the largest tax cuts in 40 years, projected at nearly £45bn by 2027, together with an increase in government borrowing of £72bn (see also analyses by the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Resolution Foundation).

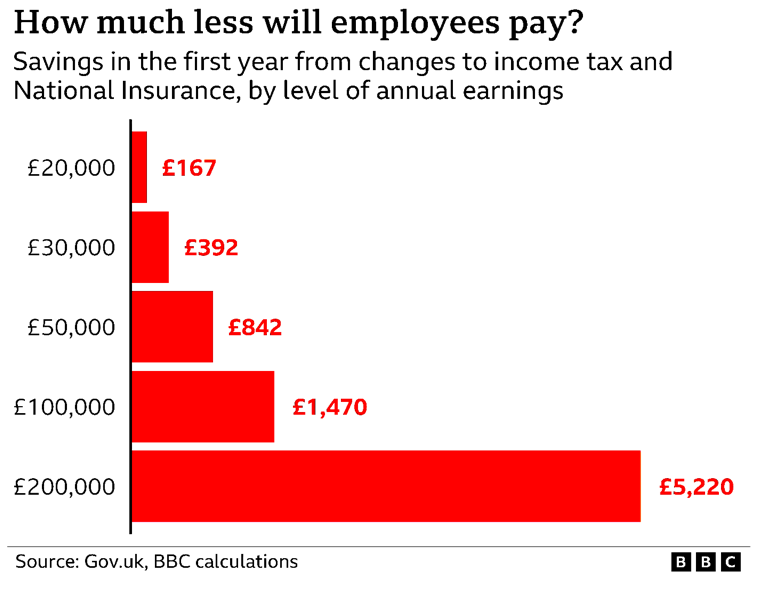

As the diagram below shows, the tax cuts are worth more for people with higher incomes, in the first year reducing income tax and national insurance contributions by £5,220 for someone earning £200,000 per year, and by £167 for someone earning £20,000 per year (slightly more than full-time work at the minimum wage).

Figure 1: Employee savings from the 23 September mini-budget

Source: BBC, 24 September 2022.

However, the tax cuts will decline over time because the level of income at which people start to pay income tax (currently £12,570 per year) is frozen. As incomes rise, in part because of inflation, more people will pay income tax and/or pay tax on more of their income – an effect known as ‘fiscal drag’. Depending on rates of inflation, the tax cut for low earners may become a tax increase.

The government’s claim

In making his announcement, the Chancellor of the Exchequer said that the package would ‘turn the vicious cycle of stagnation into a virtuous cycle of growth’. The claim, in short, is that tax cuts will lead to a sustained increase in the UK’s growth rate – note sustained, not a short-run boom followed by a bust.

The argument, sometimes referred to as ‘trickle down’, is that even though tax cuts are higher for the best-off, the effect will be to drive up economic growth, raising living standards for everyone including those of lower earners (‘a rising tide lifts all boats’).

How likely is the policy to work?

That tax cuts alone will not have that effect is agreed by a weighty centre of gravity of the economics profession, for example Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman, Martin Wolf (in an article subtitled ‘It is surely a fantasy that further tax cuts and deregulation will transform performance’), and the International Monetary Fund. LSE research in 2020 reached a similar conclusion.

Why not?

To explain why simple tax cuts do not increase growth it is helpful to start with an analogy. Science typically starts with simple models: engineering, for example, starts from the assumption of zero friction. Models of that sort are useful for developing an understanding of the main driving forces but – precisely because they are deliberately simple – are a bad basis for policy. A car designed assuming zero friction would have no lubrication system and no cooling. A vehicle with a seized-up engine block won’t get you to the shops, let alone to the end of an Amazon delivery round.

The government’s policy of tax cuts is based on the equivalent economic model. To stand a chance of working, a policy needs to take account of deviations from the simple ideal. In this century alone, multiple Nobel prizes – 2001 (imperfect information), 2002 and 2017 (behavioural economics), 2010 (search frictions) and 2016 (incomplete contracts) – have been awarded for work that explains why markets may not be efficient.

Selecting only a few examples from a long list, policy needs to take account of:

1. The time dimension, e.g. the time it takes for large projects to take effect or the time it takes to train a doctor.

2. Public investment, including in skills, health and physical infrastructure, as a necessary complement to the productivity of private investment.

3. Co-ordination problems, which arise where large-scale things need to happen at the right time and in the right order, e.g. a large-scale move away from internal combustion engines requires prior expansion of electricity generating capacity and the roll out of mass charging facilities for electric cars.

4. Market pricing may fail to take account of the damage caused to others, most obviously the damage to climate and biodiversity caused by burning fossil fuels.

Absent proper attention to these factors, tax cuts will fail to generate higher growth. The theory is confirmed by experience. If the government’s claim is right, countries with low taxes would have high growth rates. There is no such simple pattern. Other countries, including France, Germany, and Canada have higher taxation than the UK, but also higher productivity, faster growth and less inequality.

What could go wrong?

In contrast with the virtuous circle claimed by the Chancellor, the worry is the risk of a downward spiral.

Worry 1: Little increase in the long-term growth rate, perhaps in part because of the lack of the necessary complementary previous and current public investment, all affected by budget cuts over the past decade. The resulting problems include:

1. An increase in demand (because of the tax cuts and additional borrowing) with little or no parallel increase in supply will lead to inflation, i.e. a toxic combination of low growth and inflation (‘stagflation’).

2. Inflation creates upward pressures on interest rates (adding to the cost of mortgages (for low and medium earners more than offsetting any gain from lower taxes) and higher costs to taxpayers of repaying government borrowing.

3. Inflation also risks downward pressure on the value of sterling (raising the prices of imported goods – food, gas, oil, etc.), further aggravating inflation.

Worry 2: Little or no reduction in inequality, which in the UK is the second highest among the advanced economies. Even if a rising tide did indeed lift all boats (itself contested), if there is no rising tide boats won’t rise.

Worry 3: A series of unintended consequences that will emerge over time. As a small example, reducing the basic rate of income tax (the rate paid by most taxpayers) from 20% to 19% will hit charities. Under the rules for GiftAid, with a basic rate of tax of 20%, a donation of £100 is worth £125 to the charity. With a 19% tax rate, the donation is worth £123.46. The difference may appear small, but in aggregate is large – and all the more so at a time when people’s living standards are under pressure.

Message for policy makers: over-simplification is not the same thing as clarity. Please think again.

Watch Professor Nicholas Barr explain why inflation in the UK is rising and why it could have been predicted.

#LSEUKEconomy: Explore our dedicated hub showcasing LSE research and commentary on the state of the UK economy and its future.

___________________

About the Author

Nicholas Barr is Professor of Public Economics at the London School of Economics’ European Institute. A range of academic and policy writing can be found here.

Nicholas Barr is Professor of Public Economics at the London School of Economics’ European Institute. A range of academic and policy writing can be found here.

Featured image credit: Rory Arnold / No 10 Downing Street (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)