The working classes still get less of everything in education, including respect, argues Diane Reay. She suggests that in order to move towards a fairer educational system, England needs to implement a National Education Service that provides the same standards and level of resources to all children, regardless of class and ethnic background.

The working classes still get less of everything in education, including respect, argues Diane Reay. She suggests that in order to move towards a fairer educational system, England needs to implement a National Education Service that provides the same standards and level of resources to all children, regardless of class and ethnic background.

Historically, the English educational system has educated the different social classes for different functions in society. However, in the 21st century, the expectation is that the English state system is providing roughly the same education for all. In my new book I argue that it does not. Even within a comprehensive school, when young people are all being educated in the same building, the working classes are still getting less education than the middle classes, just as they had when my father was educated at the beginning of the 20th century. We are still educating different social classes for different functions in society.

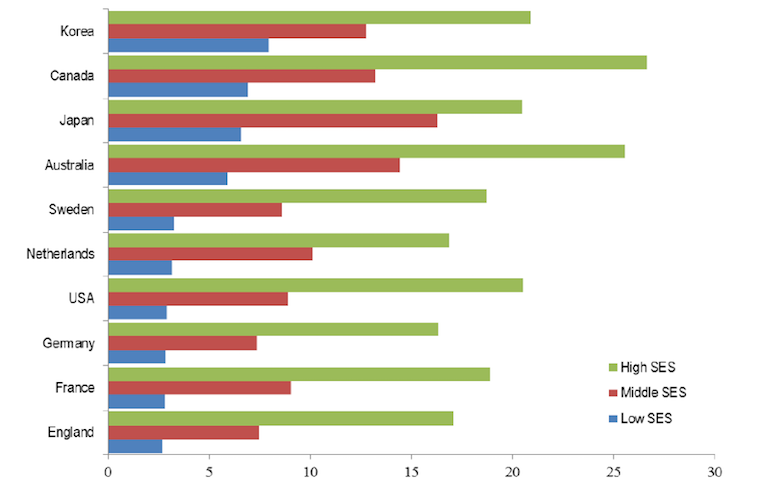

The book is based on a mix of statistics, more than 500 interviews and my personal memoir of growing up as a free school meal child living on a council estate. The book argues that, despite a whole plethora of policy initiatives from testing regimes, league tables, school choice, academies and free schools, the return to traditional models of both primary and secondary curriculum and to a preoccupation with ‘school improvement’ and ‘school effectiveness’, little has changed in relation to how the working classes are valued within education. And despite the incessant focus on social mobility, England is at the bottom of the league table for working class children achieving high academic levels.

Figure 1. The percentage of high achieving children by family background for selected countries

Source: OECD, 2010

Source: OECD, 2010

The academy and free school movement has made things worse for working class children, with more segregation and polarisation, and a growth in the unfair distribution of resources. So, for example, £96m originally intended for improving underperforming schools was redistributed to academies.

In spite of free schools and academies receiving more funding per pupil than state comprehensive schools, they typically educate fewer children in receipt of free school meals, and have a more advantaged intake than the comprehensive schools do.

England does not have an education system that is serious about realising the potential of all children, with those on free school meals and receiving pupil premium 27% less likely to achieve five or more GCSEs at grades A*-C, including English and maths. Four-fifths of children from working-class minority ethnic families are taught in schools with high concentrations of other immigrant or disadvantaged students – the highest proportion in the developed world, according to a report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Half of all free school meal children are educated in just a fifth of all schools.

There are predominantly middle-class comprehensives and predominantly working- class and ethnically-mixed comprehensives – and despite all the rhetoric around pupil premiums, pupils in the more working-class comprehensives get less money per head. They get fewer qualified teachers. They get higher levels of teacher turnover and more supply teachers. Even if they are in the same schools as middle-class children, they are in lower sets and yet again they get less experienced and more supply teachers. Working class children also get a more restrictive educational offer. Since the schools attended by most working class children are not doing well in the league tables, there is a lot of pressure on their teachers and headteachers to increase their league table position. That means a more concentrated focus on reading, writing and arithmetic than in schools serving more affluent intakes.

All the children I interviewed had a powerful sense of their position in the academic hierarchy. From reception, growing numbers of children are in sets aged four, and they can tell they’re only in ‘the monkeys’, which is not a good group to be in. That means they’re not very clever. But latest research shows that it is the wealth and inclination of parents, rather than the ability and efforts of the child, that have the most bearing on a child’s educational success today. If you’re a working class child, you’re starting the educational race halfway round the track behind the middle class child. Middle and upper class parents are able to guarantee their children’s educational success through private tuition, extra resources and enrichment activities.

Image credit: Copyright, Ros Asquith, used with permission

Image credit: Copyright, Ros Asquith, used with permission

In particular, the difference between amounts spent on educating children privately or in the state sector is stark. Research from University College London that found £12,200 a year is the average spending on a privately educated primary pupil, compared with £4,800 on a state pupil. For secondary, it’s £15,000 compared with £6,200.

To make things worse, an analysis of Department for Education data reveals that schools with the highest numbers of pupils on free school meals are facing the deepest funding cuts: in secondary schools with more than 40% of children on free school meals, the average loss per pupil will be £803. That’s £326 more than the average for secondary schools as a whole. And primary schools with high numbers of working class pupils are expected to lose £578 per pupil.

Another disturbing trend is the disrespect with which working class children are treated in some super-strict schools. Some academies operate on the principle that working class families are chaotic and children need school to impose control. There’s lots of lining up in silence, standing to attention when an adult comes into the room, and chanting mantras.

The OECD has consistently pointed out that increasing the social mix in schools improves the attainment of working class students without affecting that of their more privileged peers. It also decreases the social distance between different groups of children and helps to allay the mistrust, wariness and anxiety about those who are different from us. That mistrust obviously came out in the Brexit vote. Yet, if you put children together in classrooms, they start to learn that what they share is much greater than the differences between them.

______

Note: this article draws from the author’s latest book, Miseducation: inequality, education and the working classes.

Diane Reay is Visiting Professor of Sociology at the LSE and Emeritus Professor of Education at the University of Cambridge. Her new book Miseducation: inequality, education and the working classes was published by Policy Press in October 2017.

Diane Reay is Visiting Professor of Sociology at the LSE and Emeritus Professor of Education at the University of Cambridge. Her new book Miseducation: inequality, education and the working classes was published by Policy Press in October 2017.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

From my own research also, I think you are spot on Diane as the educational divide seems to very much still be in existence despite the great efforts of many people to bridge this divide by social class. I’ve added your book to my reading list. All the best.

Thank you for this interesting summary, Professor Reay. I wonder if you could possibly add a link to the OECD figures you used as I cannot track them down, and the only 2010 education data their website admits to seems to be in a book which one has to buy. I have no knowledge of current work on education statistics, but the data you show on Sweden for instance is at odds with the rather close grouping given in the UNESCO chart at http://www.education-inequalities.org/indicators/higher_1822#?sort=mean&dimension=all&group=all&age_group=enrol_higher_1822&countries=all

Jim’s suggestions are interesting if worrying: but I think he is unduly pessimistic about the necessary future for “developed” economies

I would also note that in the chart you give, England does not seem to be significantly worse than Germany, and in fact both nations seem to do badly on tertiary education for all groups. However the OECD report Educational Opportunity for All(2017) certainly bears out some the points you are making about diversity within schools, even within classes, being important for instance.

Interesting article, but a genuine question. Why does your headline and introduction refer to the ‘UK’ when the article is clearly about England?

What sticks out from your SES chart and the related OECD PISA charts is that the UK is pretty similar to our European neighbours and rather below selected younger developed nations. Question is why the difference.

Possibly the older economies have had time for society to stratify more completely. This might suggest a more or less permanent division by class or ability as economies mature. A bit depressing for social scientists and possibly not very PC.

Or governments in mature economies have found that it really does not pay to invest much in the lower classes. They can get quite enough high level workers from the existing setup and through imports. Investing in the lower classes creates unfulfilled expectations in housing and job prospects that cannot be met without upsetting land use policies and housing policies. There is a delicate socio economic balancing act going on here.

I would agree that the UK (and many of our neighbours) are educating different classes differently. This could be that they are missing an opportunity but I suspect the truth is that mature economies will not find universally equal education worthwhile. For political reasons they must not say this and equality must be overtly encouraged but behind the scenes inequality will be the reality.

What does seem clear is that there is no obvious economic advantage to a mature economy in massively improving the education of the lower classes. If there were we would see one or two of our neighbours pulling away. A closer look at German and French education and industrial policy over the next decade might be interesting in this regard.

It would be interesting to know if at an individual level if there is a relationship between the amount of education investment in childhood and the amount of consumption of government services over a lifetime.

Indeed the introduction of comprehensive schools took away a huge advantage for the children at the bottom of the pile to be able to get a better education. I got a better education because of them being there, and the people at the secondary moderns who would never have been top of the class in a comprehensive got the chance to be top in a secondary modern giving them a boost to their ego’s which helped later on in life, but then common sense and educational theory seldom match these days, it has to be all PC.