The government aims to shift the UK towards a high-skill, high-wage growth model, based on investment in education. Nick O’Donovan explores how this ambition was shared by New Labour politicians in the 1990s, and what lessons we can learn from the shortcomings of that agenda.

The government aims to shift the UK towards a high-skill, high-wage growth model, based on investment in education. Nick O’Donovan explores how this ambition was shared by New Labour politicians in the 1990s, and what lessons we can learn from the shortcomings of that agenda.

Over recent months, the UK government has repeatedly invoked the idea of a high-skill, high-wage economy. In his speech to the 2021 Conservative Party conference, Boris Johnson claimed that his party would ‘solve the national productivity puzzle… by investing in skills, skills, skills’. Rishi Sunak’s Autumn Budget argued that ‘providing a world-class education to all our people’ would help to create a ‘higher-wage, higher-skill, higher-productivity economy’. On this account, social investment in workers’ human capital will increase their productivity, thereby enabling them to command higher wages.

Should this endeavour succeed, it would entail a marked change to the UK’s ‘growth model’. In recent years, political economists have used the concept of ‘growth models’ to explore how sources of aggregate demand shape social, political and economic outcomes. Does growth rely on business investment, household spending or net exports? Is it sustained by rising productivity, or by increased levels of borrowing? Is it driven primarily by rising wages or rising profits?

Prior to the global financial crisis, the UK’s growth model was largely predicated on consumer spending, propped up by borrowing that was inspired to no small degree by rising house prices. This ‘privatised Keynesianism’ saw households rather than government step in to support demand by taking on debt, a growth model which unravelled in spectacular fashion with the financial crash. Despite this chastening experience, the Coalition government (wittingly or otherwise) ended up reinstating the same approach, reliant on consumer spending buoyed by rising house prices.

Proponents of a high-skill, high-wage alternative model hope that social investment in skills (alongside infrastructure and research) will suffice to push up salaries. In theory, this should lead to a sustainable wage-led growth process, with higher wages based on higher labour productivity acting as a more sustainable source of consumer demand than borrowing secured against speculative asset price bubbles.

What advocates of this brave new growth model often neglect is that this strategy has been tried before. In 1997, the incoming New Labour government plotted a course towards a high-skill, high-wage economy through social investment. In the 1990s, as today, public spending on education and skills was celebrated as a way of improving living standards by raising productivity and thus wages, and as a substitute for conventional forms of welfare that would lift people from poverty by empowering them to find better-paid work. Underpinning this claim stood an analysis of long-term changes in the economies of advanced capitalist democracies, in particular the rise of the so-called ‘knowledge economy’. Knowledge-intensive businesses – ranging from software companies to the creative industries, from the financial sector to pharmaceuticals – were supposedly becoming increasingly important drivers of jobs and growth. ‘Knowledge work’ would play an increasingly prominent role in other sectors, too, with skilled workers required to automate routine functions (such as order-taking) in the new digital age.

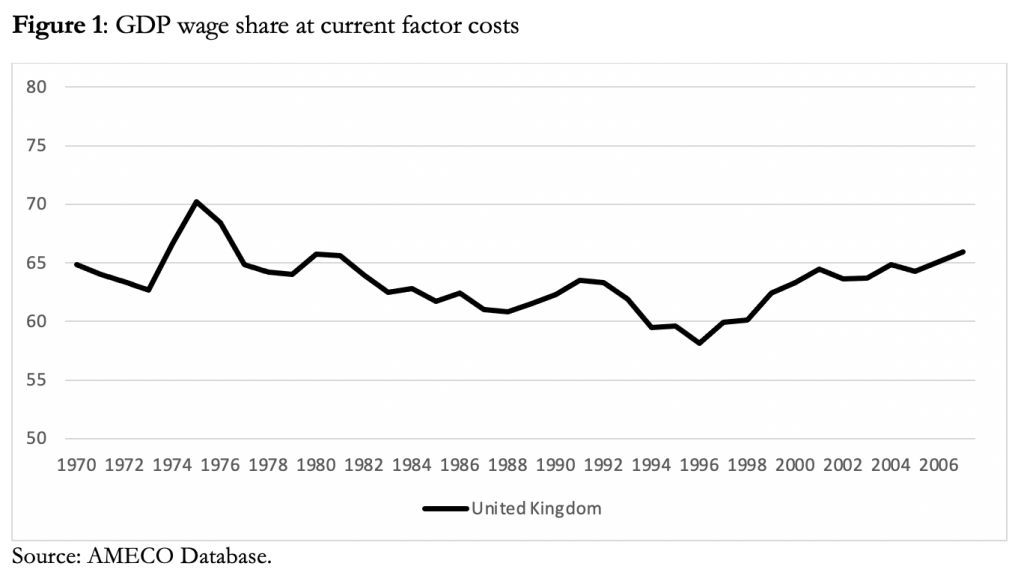

From a growth models perspective, these changes had the potential to transform the nature of the UK economy. Over the course of the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher’s reform agenda had shifted national income towards capital, to the detriment of wage-earners (see Figure 1). By weakening trade unions and curtailing employee rights, as well as reducing the generosity of welfare payments to out-of-work households, Thatcher strengthened the negotiating position of employers relative to their employees. Yet because growth remained stubbornly dependent on consumer spending – because the UK economy remained resolutely wage-led, rather than profit-led – the result was a mismatch between the pro-capital distribution of national income and the rising wages necessary to drive growth. Under these circumstances, the expansion of household debt substituted for robust increases in wages as a source of demand.

The rise of the knowledge economy, by contrast, appeared as though it might shift the dial in the other direction. According to early evangelists of knowledge-driven growth, the move towards more knowledge-intensive forms of production would strengthen the bargaining power of labour (at least, skilled labour) relative to owners of capital, as knowledge-intensive production depended more upon the input of skilled workers, and less upon traditional investments in plant and machinery. As Geoff Mulgan – co-founder of the thinktank Demos, who would go on to lead the Number 10 Policy Unit under Blair – claimed in his 1997 book Connexity, ‘in the twenty-first-century economy the most valuable things are rarely physical, and it is possible to create wealth almost out of nothing, or rather nothing more than ideas’. Provided workers were equipped with in-demand skills, countries could retain the market liberalising reforms of the 1980s, while simultaneously re-empowering labour relative to capital.

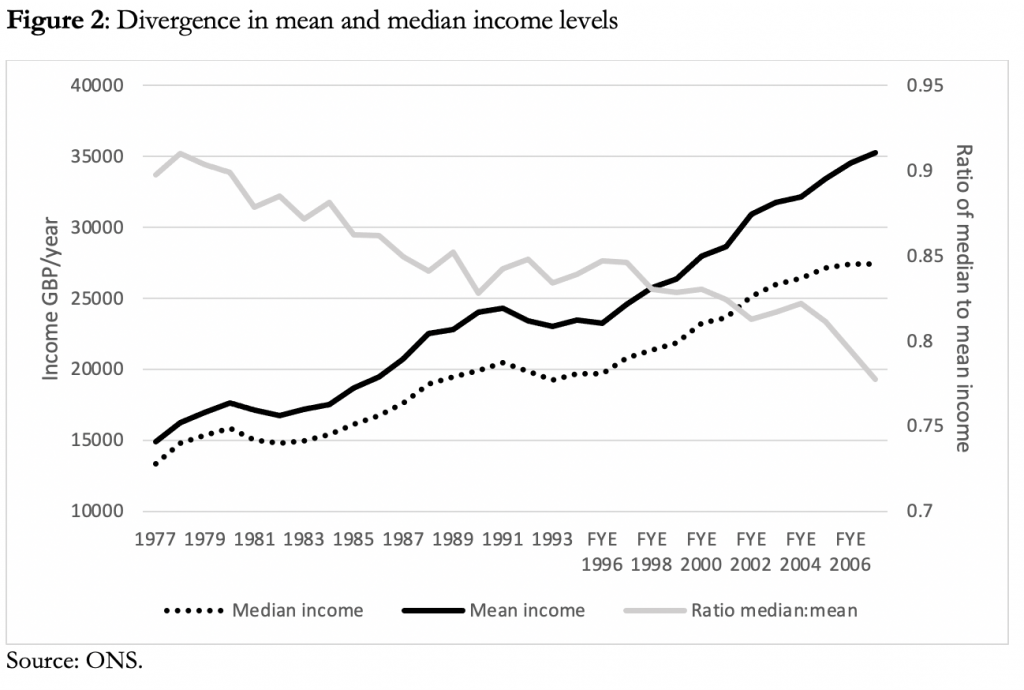

Interestingly, at least in the UK, the labour share of national income did recover over the course of the 1990s and early 2000s (see Figure 1), a development consistent with these accounts of the dynamics of knowledge-driven growth. Yet this did not herald the beginning of a stable wage-led demand regime, because the headline rise in labour income was accompanied by an increase in wage inequality (see Figure 2).

Distribution matters to growth models. Under a wage-led demand regime, a shift in national income towards labour should increase consumer spending and thus encourage investment and growth. This assumes that wage-earning households have a higher propensity to consume than their more affluent counterparts, who receive a disproportionate share of capital income. However, if the same increase in labour’s share is itself skewed towards more affluent households, then wage-led demand growth will fail to materialise, as the proceeds of growth still accrue to those with a lower propensity to consume. Consequently, in the UK growth continued to rely on household debt and rising asset prices over the 1990s and 2000s, exposing the economy to a sharp fall in demand when credit creation and asset price inflation stalled.

Does this mean that Labour’s efforts to implement a high-skill, high-wage economy were inherently flawed? Not necessarily. Arguably, the window of time before the global financial crisis hit was too short a period over which to assess the outcomes of long-term educational investments, several of which were unwound during the austerity era that followed. Had commitment to a high-skill, high-wage economy continued, perhaps wage inequality would have fallen, as an increase in the supply of skilled labour competed down the wage premium commanded by the best-educated, leading to broad-based wage-led demand growth. This assumes that wage inequality would have been reduced by increasing the supply of skilled workers, and that increasing the supply of skilled workers would not have strengthened the bargaining position of capital relative to labour. However, to the extent that wage inequality was a product of superstar effects (the concentration of demand on the most successful individuals and firms), rather than the scarcity of skilled labour, increased social investment would have had minimal impact on the dynamics of inequality and thus demand. (Significantly, the rise of the knowledge economy has been widely understood to increase the prevalence and size of superstar effects.)

Similarly, if capital remains important in the knowledge economy era – if today’s knowledge-intensive businesses need deep pockets to fund massive R&D costs and long periods of loss-making while they achieve the scale necessary to compete – then increasing the supply of skilled workers may simply reduce the price that employers need to pay for the labour required to generate returns on knowledge assets such as intellectual property, user networks and customer-generated data.

In sum, there is a risk that the creation of a high-skill, high-wage economy will require more than the social investment agenda abandoned by the austerity-championing predecessors of today’s government. Nevertheless, such investment would at least be a start.

_____________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in the British Journal of Politics and International Relations.

Nick O’Donovan is a Senior Lecturer in the Future Economies Research Centre at Manchester Metropolitan University. His book, Pursuing the Knowledge Economy: A Sympathetic History of High-Skill, High-Wage Hubris will be published by Agenda in May 2022 and is available for pre-order here.

Nick O’Donovan is a Senior Lecturer in the Future Economies Research Centre at Manchester Metropolitan University. His book, Pursuing the Knowledge Economy: A Sympathetic History of High-Skill, High-Wage Hubris will be published by Agenda in May 2022 and is available for pre-order here.

Photo by kaleb tapp on Unsplash.