Steve Keen was one of the few economists who publicly predicted the Great Recession that still troubles developed economies. In this interview with Joel Suss, he explains how he came to that conclusion, offers his view on UK economic policy, and presents his own policy ideas for ending speculative, risky behavior that created the debt burden to begin with.

Steve Keen was one of the few economists who publicly predicted the Great Recession that still troubles developed economies. In this interview with Joel Suss, he explains how he came to that conclusion, offers his view on UK economic policy, and presents his own policy ideas for ending speculative, risky behavior that created the debt burden to begin with.

Can you explain what led you to believe there would be an imminent economic calamity when you first raised warning signs in 2005?

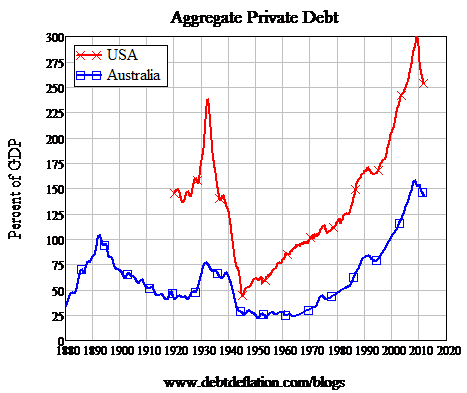

Looking at the empirical data – looking at the ratio of private debt to GDP, it was obvious. If you look at the ratio [Figure below], you can see that it is obviously of systematic control. In American data going back to 1920 you’ll see the peaks and then collapses in the ratio of debt to GDP have always coincided with depressions. In the 20s and 30s debt went from about 100 per cent of GDP in the early 1920s to 175 per cent in 1929-30 and then 235 per cent because of deflation in 1932 then plunged back down to 45 per cent of GDP through WWII. It rose to 303 per cent of GDP in early 2009, and has now fallen to 250 per cent. No period in the last 100 years compares to where we are now except for the great depression. Empirically, you have to explain how that debt grew, why it grew so much more rapidly than income, why has it gone in reverse, and why does it matter.

There is a lot of debate in economic circles and amongst political leaders between reducing debt and propping up aggregate demand; between austerity and stimulus. What is your opinion?

The better of two bad policies is the stimulus approach. If you have the private sector deleveraging and the public simultaneously trying to reduce its debt level, and banks are afraid to lend anyways because so much bank debt has gone bad, then you have the amount of money in the economy being reduced; two factors both taking money out of circulation which will push the economy down further. The irony is that you’re trying to repay debt, but the debt doesn’t fall when you go into austerity. This is the mistake of making the analogy between the household and the economy. In a household, if you decide to spend less your income doesn’t necessarily change, therefore you can pay the debt down. But in a society, a reduction in the rate of turnover of money makes everybody’s income drop in the aggregate but the debt remains at the same level. You pay it down a bit but quite possibly in a year’s time you’ll have a higher ratio of debt to income than you had beforehand. That’s what happened disastrously during the great depression.

You’ve talked about the importance of macroeconomic models incorporating the endogenous creation of money by banks. Can you explain this idea?

Banks are required to have reserves based on the deposits they had between 30 days and 50 days earlier. Lets say you have a bank that is already at the reserve limit and someone comes in with a great idea and the bank likes the idea and extends the loan. If they extend the loan they create a loan and create a deposit and therefore breach the reserve ratio. But they know they have 50 days to raise the money.

The loans you make next week should be based on the reserves you had last week, which are not the laws, so you would have to have a drastic change to the legal structure to have the exogenous creation of money be legally enforced. But the reality is that we’ve seen this huge growth in the shadow banking sector. Every time policymakers try to control the banks behavior they invent a way around it, through legal loopholes or whatever.

Therefore, I model the banking sector as if there were no constraints to what it does. It simply lends unrestrained. With that system I get results that look much more like the real world. I get the booms and crashes and so on.

You’ve described the banking sector as parasitic. What do you mean by this?

You necessarily need banking to expand the money supply to finance investment. Change in debt is the main source of financing of investment. Schumpeter and Minsky made the case that the change in debt is the main source of investment funds – so you need that for a healthy functioning of the capitalist system. Also the change in debt finances purchasing of financial sector assets. So you get a relationship between the change in debt and not just investment, which you want, but also speculation on the value of assets, which you don’t want because that’s where the bubbles come from. What you get is a positive feedback process. The change in debt actually sustains the prices of financial assets, therefore the acceleration of debt determines which direction those prices are going to go – therefore if you have accelerating levels of debt you have rising asset prices which of course sucks people back in again. That’s what gives you a bubble and that’s why the bubble has to burst.

How would you end speculative, risky banking behavior so as to avoid asset bubbles?

What you need to control risky banking behavior is a set of policies that break the link between change in debt and asset prices. And I’ve put forward two ideas and these are post crisis ideas because the crisis itself isn’t addressed by them. One of them is to redefine shares in what I call jubilee shares.

The idea would be at the moment when you buy a share it lasts forever. That enables people to say, buy these shares in this strange company called yahoo, which you can currently buy for 20 bucks and in a years’ time it is guaranteed to be 1000. And of course it goes from 20 to 400 and right back down to 20 once more 4, about the price it is now. And only because there’s no limit to the number of times it can be sold, and therefore it lasts forever,

What I propose is that with jubilee shares, if you bought a share from a company in an IPO, yes it lasts forever, just like it does now. You could sell it someone else but only a defined number of times. My idea, using a biblical idea, is seven times. That gives you enough of price discovery to get a realistic idea of what the company should be priced at. But after the seventh time it lasts 50 years and then it expires. And the idea is that it would take a blithering idiot to borrow money to buy jubilee shares. So you remove the incentive between rising debt levels and asset prices in the share market.

The other policy I call the PILL – property income limited leverage. At the moment if you and I are competing over a house in London somewhere and you and I both had the same amount of income and money saved, and we went to a bank and you got a 95 per cent loan to valuation ratio for your income and I got a 94 per cent you’d get the place. We both have an interest in bidding up the amount the bank will lend to us to buy the house – which is what causes housing price bubbles. So my idea for the pill is that the amount of money that a bank can lend is limited not by the income of the people competing for the house, but the income earning capacity of the house they want to buy. So you and I are both fighting over a place which say could earn 50k pounds a year in rent, then the max that you or I could borrow from a bank is half a million pounds. And then if you wanted to beat me you need to save more of your income then I did. Then you get a negative relationship between house prices and leverage rather than a positive one.

So those two rules alone would mean that the attractiveness of borrowing money to gamble on rising asset prices would not be completely eliminated – you could not eliminate it totally – but would be reduced enough that it would no longer be a problem.

What’s in store for UK economy considering the high private debt to GDP ratio?

I’ve analyzed the data recording the private debt to GDP ratio in England at the moment. It’s 450 per cent, 250 per of which is financial sector debt alone. America peaked at 300 per cent. It’s actually the rate of change of the debt that has an effect on aggregate demand.

In England the change in debt bounced around like the cardiogram of somebody about to duffer a cardiac arrest. At various times, given the substantial amount of debt, the change in debt was equivalent to around 60 per cent of GDP in nominal terms.

It shows the extent to which this is a Ponzi economy. I don’t think the growth in debt can be sustained any longer. Now you’re seeing the debt to GDP ratio falling about. At some point it will go strongly negative. All the instruments people have swapped around town and called assets will be regarded as toxic. I shall not be surprised if there is a severe credit crunch in England in the next one or two years.

Now the deleveraging crisis will be more severe here than in America because your deleveraging from a far higher level of debt. Of course, because the government is running an austerity programme, the government may well trigger it. With a fall of demand that comes out of the austerity programme feeding back in to private behavior – causing a slowdown in the rate of private debt – and all the hot money that’s been part of the prosperity of this town deciding to relocate back to wherever it came from, it will be serious credit crunch material.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Steve Keen is Professor of Economics & Finance at the University of Western Sydney, and author of the popular book Debunking Economics, a second edition of which has just been published (Zed Books UK, 2011; www.debunkingeconomics.com). He will be delivering a public lecture at the LSE on 3 April 2012. Steve blogs at http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/ and is on Twitter: @ProfSteveKeen.

Joel Suss is Assistant Editor of the British Politics and Policy blog and a student at the LSE.

Does the fact that there are no other comments on this mean that no one at the LSE is interested in Keen’s ideas? Is anyone in British politics listening and interested I wonder? I’m interested. But not an economist. I came looking for reactions from the informed.

Keen has pointed out that our UK private debt is much higher (ca 450% of GDP), that unlike the US it hasn’t been coming down, and that a Lehman Bros. style credit crunch is quite likely.