Comparing parliamentary debates on intervention in Syria in 2013 and 2018, James Strong finds that support for the latter depended on Theresa May’s decision not to call a vote prior to deployment, as well as on the shifting attitude among MPs since 2013, in particular vote-switching among Conservatives.

Comparing parliamentary debates on intervention in Syria in 2013 and 2018, James Strong finds that support for the latter depended on Theresa May’s decision not to call a vote prior to deployment, as well as on the shifting attitude among MPs since 2013, in particular vote-switching among Conservatives.

On 29 August 2013, the House of Commons dramatically vetoed military intervention against the Assad regime in Syria. The shell-shocked prime minister, David Cameron, confirmed he would accept the result; ‘the British Parliament, reflecting the views of the British people, does not want to see British military action. I get that, and the Government will act accordingly’.

Yet just under five years later, in April 2018, Prime Minister Theresa May ordered an essentially identical operation to the one Cameron proposed. Not only did she avoid calling a prior parliamentary vote, she subsequently won majority support for what she had done.

In recent research, I ask why May won while Cameron lost. I consider a number of possible explanations, including the fact his vote preceded military action while hers followed it, changes in the balance of power between the parties in parliament, changes in the makeup of the parties in parliament, and changes in attitudes among MPs.

I find, above all, that May’s decision not to call a prior vote made the decisive difference. It is easier to ask forgiveness than permission, and you cannot lose a vote you do not call. Although two votes did take place in 2018, both followed motions by Labour MPs critical of May’s government in general, not just its specific actions in Syria – the below data uses voting figures from Jeremy Corbyn’s motion on 17 April. That made it easier for Conservatives to rally to the government’s support. Moreover, by acting first, May avoided two problems that Cameron faced.

First, she did not struggle to deal with hypothetical objections. With memories of Iraq looming large, Cameron failed to assuage MPs’ concerns that any intervention in Syria would inevitably go wrong. He did not help his case by publishing an intelligence dossier on Syrian weapons of mass destruction alongside a summary note from the Attorney General explaining why intervention was legal. May’s operation was over by the time she reported it to the House. It had not in fact triggered a confrontation with Russia, caused large-scale civilian casualties or dragged UK ground troops into the Syrian Civil War.

Second, May did not have to ask backbench MPs to support her on a conscience issue. With the actual fighting already in the past, the votes in 2018 concerned only the question of whether the government had acted properly. There was no question – as there had been in 2013 – of MPs’ actions leading directly to violence and destruction.

So May’s decision to act first and ask permission later paid off. But there was more to it than that. At a secondary level, she benefitted from changes in parliamentarians’ attitudes – and, specifically, from vote-switching among Conservative MPs.

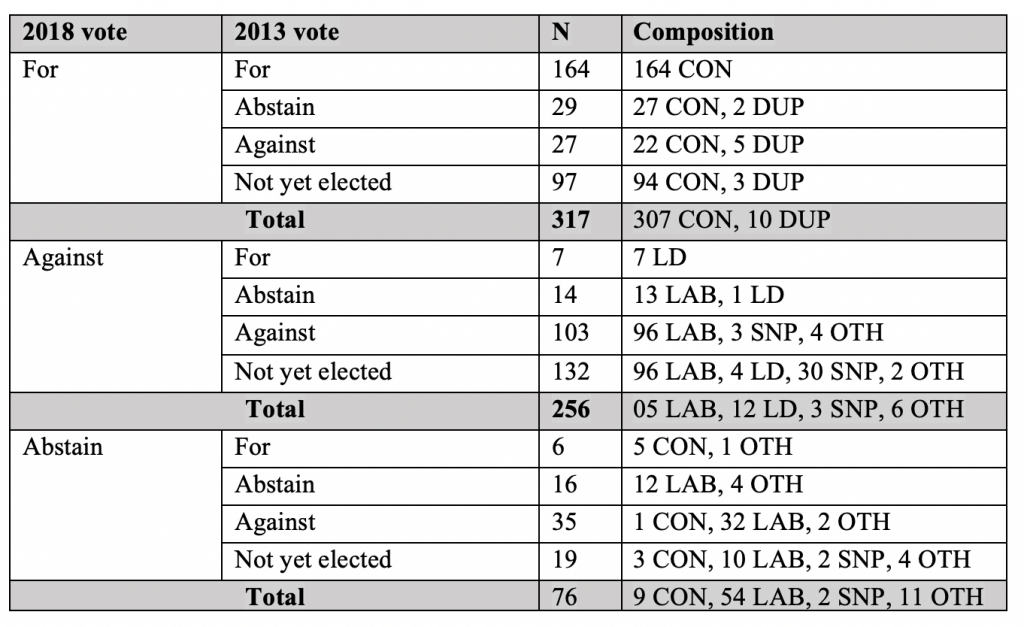

Table 1: Votes for or against the government in 2018 compared to 2013

As Table 1 shows, May’s support in 2018 comprised 317 Conservative and DUP MPs, while 256 Labour, SNP, Liberal Democrat and other party MPs voted against her, and 76 MPs did not vote.

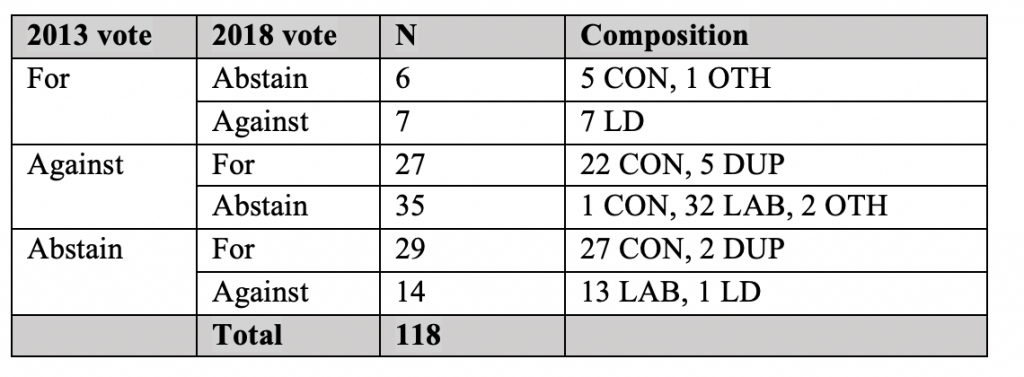

Table 2: Vote switchers, 2013 compared to 2018

As Table 2 shows, May benefitted from vote-switching among MPs who were in parliament in both 2013 and 2018. A total of 56 Conservative and DUP MPs voted with her having either voted against Cameron or abstained in 2013. By contrast, just 13 MPs who voted with Cameron in 2013 failed to support May. The net effect of vote-switching was to increase the government’s majority by 84 in 2018 relative to 2013.

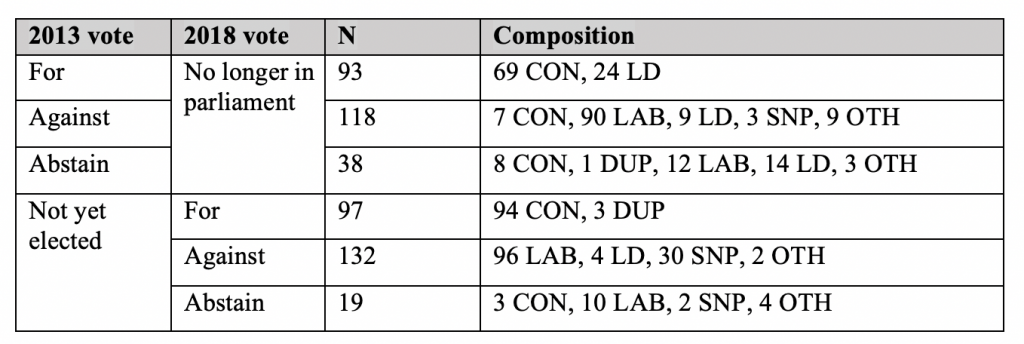

Table 3: Personnel changes, 2013 compared to 2018

As Table 3 shows, personnel changes between 2013 and 2018 boosted both the pro-government and anti-government votes while reducing the number of abstentions. This probably reflects greater political polarisation as the Conservative Party moved right and Labour moved left under the influence of Brexit and Corbynism. It was striking, for example, that all 56 new Labour MPs elected in 2017 backed Corbyn’s motion, while all of the seven Labour MPs who later defected to the Independent Group abstained. It probably also reflected the more partisan nature of the votes in 2018.

The net effect of personnel changes was to reduce the government’s majority by ten. In other words, despite the fact that one third of seats in the Commons changed hands (at least between individual MPs, less so between parties) between 2013 and 2018, this had less of an impact on the outcome of the vote in 2018 than did vote switching among those who were present on both occasions.

It makes sense, then, to consider why the vote-switchers in particular and the House in general might have changed their minds about Syria between 2013 and 2018. Table 4 sets out the results of a detailed content analysis of speeches made in debates on the two occasions.

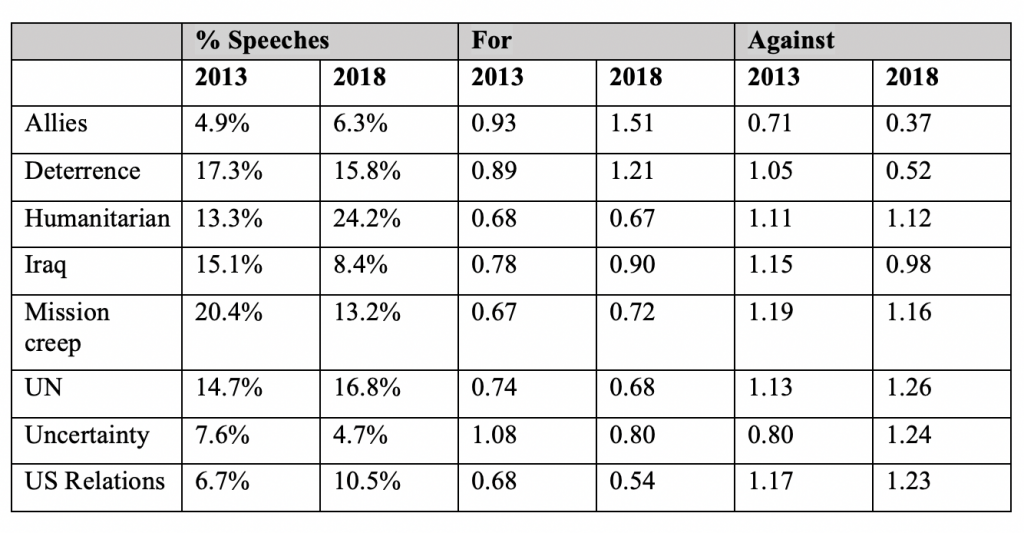

Table 4: Attitude changes, 2013 compared to 2018

The first two columns show that the issues MPs most cared about shifted between the two occasions. The proportion of speeches mentioning humanitarian concerns nearly doubled while the proportion mentioning Iraq nearly halved. There was less attention to mission creep and uncertainty in 2018 and more to allies and US relations. What intervening in Syria meant had shifted.

Moreover, as the subsequent columns show, what mentioning an issue meant had also shifted. MPs who mentioned the UK’s international allies and the concept of using military action to deter the use of chemical weapons in 2013 were more likely than the average voting MP to oppose intervention. In 2018, MPs who mentioned these were more likely to vote with the government. Those who mentioned Iraq in 2013 were more likely than average to vote against Cameron. Those who mentioned Iraq in 2018 were less likely to vote against May.

Between 2013 and 2018 many MPs – including, crucially, several Conservatives who voted against Cameron in 2013 – came to believe the outcome in 2013 had been a mistake, that the UK should in fact support its allies by using force to deter the Assad regime from using chemical weapons, and that the risk of repeating the mistakes of Iraq was less than the risk of becoming over-cautious as a consequence of Iraq. That attitude shift helped insulate May from punishment for bypassing MPs – a move that conflicted with many parliamentarians’ understandings of constitutional convention – and meant she probably would have won a prior vote.

May benefitted from the more conservative bent of her parliamentary coalition. Cameron had a tougher ideological task trying to unite his Conservative and Liberal Democrat supporters than she faced with her Conservative and DUP power base. She also made her own luck, by refusing to call a prior deployment vote. And she got away with it because of attitude shifts among MPs, and in particular because of vote-switching among Conservatives. That was how she won where he lost.

____________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in Parliamentary Affairs.

James Strong is Senior Lecturer in British Politics and Foreign Policy at Queen Mary, University of London.

James Strong is Senior Lecturer in British Politics and Foreign Policy at Queen Mary, University of London.

Photo by Shane Rounce on Unsplash.