In the first of a two-part series, Peter John explains how a systemic approach to data collection has enabled an exploration of the UK’s policy agenda and how it has changed over time.

In the first of a two-part series, Peter John explains how a systemic approach to data collection has enabled an exploration of the UK’s policy agenda and how it has changed over time.

With the help of many others, I have spent the last seven years collecting data on what policies key decision-makers in Britain have been concentrating on for much of the twentieth century and for the first decade of the twenty-first. These data series are available for everyone to use. I think they add considerable knowledge about public policy in Britain whatever people’s specialist interest, and provide a new lens for studying British politics.

The basic claim of what is called the policy agendas approach is that there are competing topics that decision-makers can concentrate on, such as health, crime, the environment and so on. So a government or other decision-maker might focus on the economy more in one year than another, say from response to the Euro-crisis, or get pre-occupied with other topics, such as the environment.

A systemic approach to data collection means one can compare over time how much attention is focused on these topics and then seek to understand why it changes. It is possible to apply the coding framework of Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones, which allows for the reliable allocation of a piece of text to a code, using both research assistants and electronic coding. The British policy agendas website has annual data going back to 1911 on what policies are promised in the Speech from the Throne (Queen’s Speech) and on what appears in laws and budgets as well as (for later periods) monthly data on public opinion, media and prime minister’s questions – and data for Scotland. This is a resource that students, journalists, researchers, civil servants and others can easily use, especially as it is downloadable from the website in excel format (as well as available from the Essex data archive), and in part II of this blog I am going to talk about the state of play with data generally on British politics and how it can be improved.

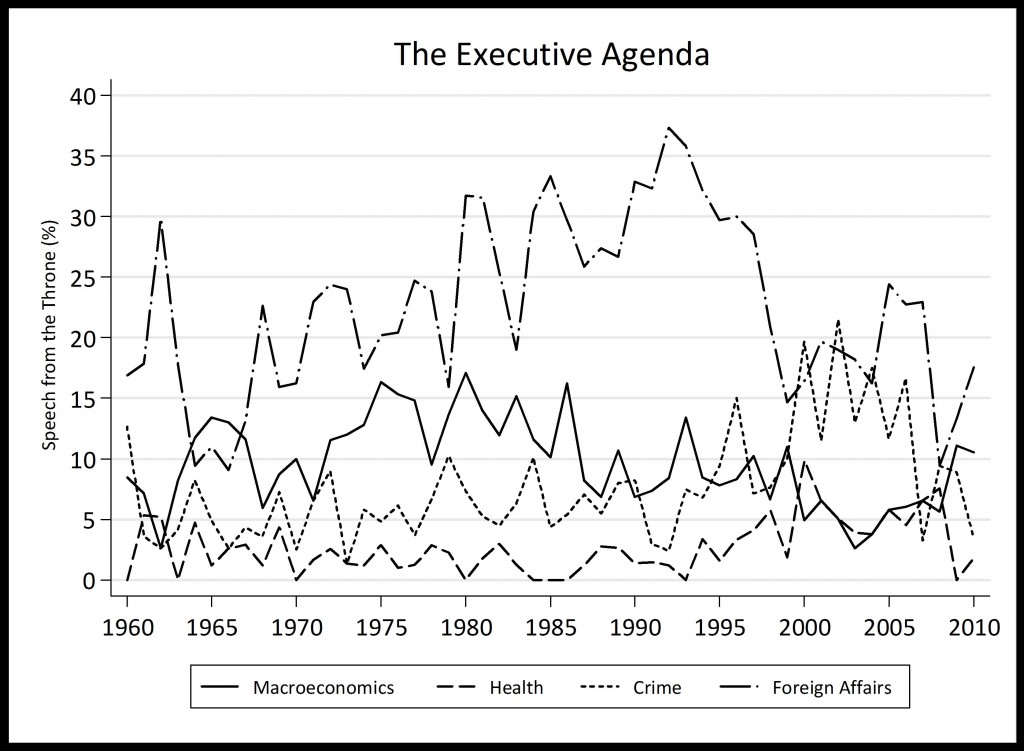

The policy agendas data can be used to test some basic claims about policy-making and understand about what is happening at the heart of government. Plots and figures show the extent of change in the policy agenda over time, such as the rise and fall (and then rise) of attention to the economy, then the growth of attention to crime and health at the end of the series. The period in government by New Labour was associated with policy on these newer issues and less concern with the economy and foreign policy. But in fact the Conservative Party had also moved in this direction before it fell from power in 1997. So graphs and figures on policy agendas enhance understanding of the basic trends in British politics.

Moreover, agendas data shows that British politics is far from stable and has experienced large lurches in decision-making, what are called policy punctuations. Yet at the same time there has been a close relationship between public opinion in the form of responses to questions about the most important problem and attention to many policy issues. We also know that governments follow on from their promises in laws topics they emphasized in the speeches, though as time has gone on the relationship between the speech and the legislative agenda has become stronger for Conservative governments, while this relationship has declined for Labour (and other) governments. So it is possible to learn a lot about how the political parties are changing their approach to governing over time.

So I hope you agree that – thanks to the British Academy, ESRC and ESF -there is a new resource that can help answer many practical questions and test new theories about British politics. For example, Tony Bertelli and myself have developed an investment framework for understanding how these policies are chosen. With Tony Bertelli, Will Jennings and Shaun Bevan, I am working on a book for Palgrave called Policy Agendas in British Politics, which will further trumpet the data and produce more findings. What I want to stress at the end of this blog is that there is a need for lots of data of this kind to advance knowledge about policy-making and decision-making in Britain. How to find it and make it more available is the subject for Part II.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Peter John is a Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at UCL. He tweets at @peterjohn10

1 Comments