The Unite to Remain alliance aims to maximise the chances of the UK’s smaller parties – the Liberal Democrats, Greens, and Plaid Cymru – having significant representation in the next parliament. Paula Surridge looks at how much supporters of each of the three parties ‘like’ the other two, and so how likely they are to support the alliance. She warns that, despite the polarisation of politics around Brexit, not all voters see remain parties as interchangeable.

The Unite to Remain alliance aims to maximise the chances of the UK’s smaller parties – the Liberal Democrats, Greens, and Plaid Cymru – having significant representation in the next parliament. Paula Surridge looks at how much supporters of each of the three parties ‘like’ the other two, and so how likely they are to support the alliance. She warns that, despite the polarisation of politics around Brexit, not all voters see remain parties as interchangeable.

There had already been much discussion of tactical voting, particularly among remain supporters, before the 2019 general election campaign got underway. But the announcement of a formal electoral alliance, Unite to Remain, between the Liberal Democrats, the Greens and Plaid Cymru has put this on a different footing.

Unite to Remain covers 60 seats in England and Wales where one of the three parties will be given a ‘clear run’ at the seat by the other two. The list of seats includes many the parties are already defending as well as key targets in this election. Although many of these were likely to have been won by the alliance parties anyway, the strategy looks sensible, especially knowing that the combined share of the Liberal Democrats and Greens in the EU parliament election topped that of the Brexit party. While a general election is a different prospect, there are at least some places on the list where the parties could combine to win a seat they would otherwise not.

But will it work on polling day? It is all very well for analysts to simply move all the votes from one column to another on the spreadsheet, but voters might not behave quite so predictably. We can look at how the supporters of each party view the other party to look at some possibilities.

A starting point is the very name of the pact ‘Unite to Remain’, which implies that each of the parties involved expect their voters’ main priority to be that they want to remain in the European Union. Data from the British Election Study suggests that while a large majority within each of the parties 2017 vote did vote remain, an explicit focus on this could lose them some of their 2017 voters who supported leave. This is least likely to hurt the Liberal Democrats whose 2017 support was overwhelmingly made up of remain voters; but for Plaid Cymru and the Greens, more than one in five of their voters voted leave in 2016. Our first step then should probably be to only move about 80% of the Green and Plaid Cymru support to the other columns in our spreadsheets.

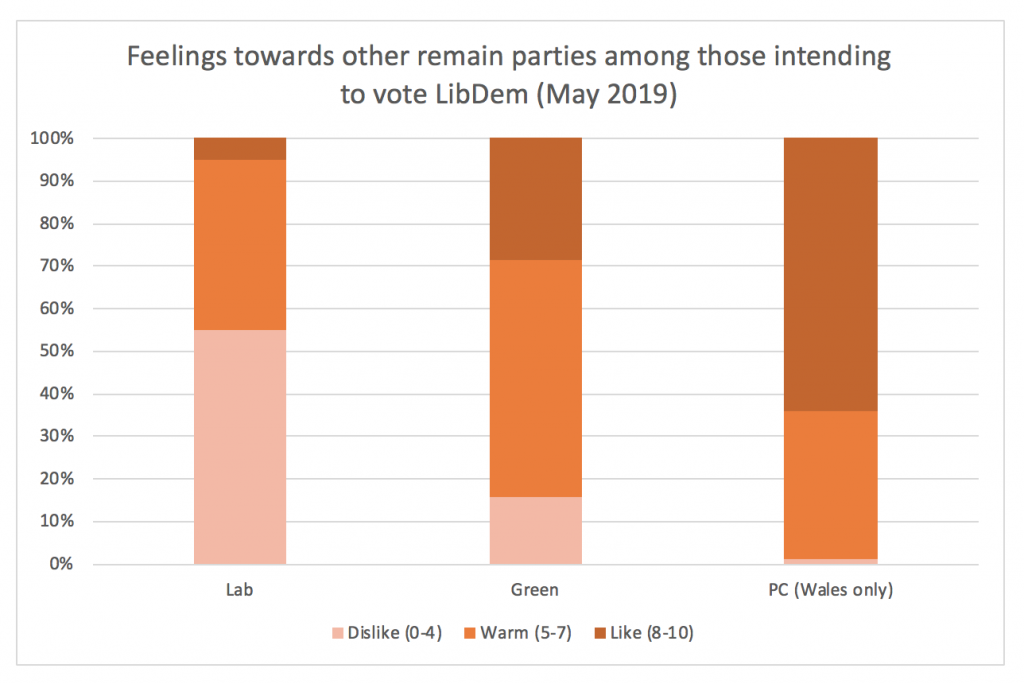

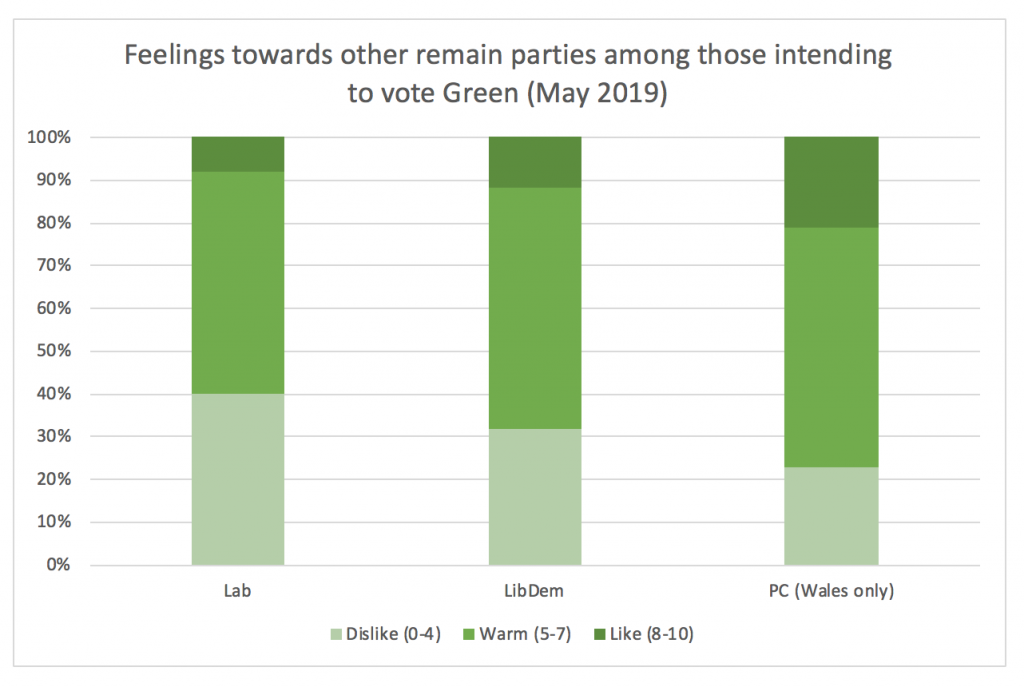

While our politics seems to have become more tribal around the Brexit divide, party loyalties have not entirely disappeared. This can be a double-edged sword when thinking about electoral pacts: party loyalty may lead voters to stay home when their preferred party isn’t standing, but it is also possible that it may lead voters to be more responsive to the cues from their leaders to switch teams. One way to see what might happen here is to look at how voters feel about the other parties. The latest wave of the British Election Study Internet Panel was collected just after the European Parliament elections in May 2019. There have, of course, been important political changes since, not least in the leadership of the Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties. Nonetheless, there are questions that were asked that are helpful to us now. Voters for all parties were asked how much they ‘like’ other parties on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 being dislike. To measure both like and dislike of the other parties, this has been divided into three parts: those giving their liking of the other party between 0 and 4 are considered to ‘dislike’ it; between 5-7 as being ‘warm’ towards it; and 8-10 as ‘liking’ the other party. These data should capture an element of how likely voters are to follow party cues. Where a party is disliked, it is unlikely even a formal party pact will move a voter to switch to that party.

The figures below are limited to those who voted to remain in the EU referendum as it is not likely that those who voted to leave will be motivated to follow the party as part of an alliance for remain. By far the largest group of voters in the alliance are those who are intending to vote Liberal Democrat – the data were collected at a high point in support for the party but this should still give a good representation of those who may be influenced by the alliance.

Those intending to vote Liberal Democrat are quite warm towards both the Greens and Plaid Cymru. Only 16% of these voters dislike the Green party, a good start for the remain alliance. It is also worth noting that over half of these voters have negative feelings towards the Labour party; despite all the talk of the need for Labour to be part of this alliance, it could be much less successful in carrying voters between Labour and the Liberal Democrats. The willingness of the Liberal Democrat voters to switch to the Greens could be critical in Bristol West where both parties have had strong support in recent elections.

The second largest group in the alliance are the Green party voters. This group are a little less warm to their larger alliance partner, with one in three Green voters having a negative view of the Liberal Democrats. This suggests that on top of the one in five who were not remain-leaning, there are a further quarter of Green voters who dislike the Liberal Democrats. So, there may be more muted enthusiasm among the Green party voters where their choice is the Liberal Democrat candidate (though where the choice is Plaid Cymru the pact looks stronger). There are relatively few seats where exactly how much of the Green party vote moves to the Liberal Democrats could be the deciding factor, but it may prove decisive in some seats where the Liberal Democrats are challenging the Conservatives.

The sample size for Wales is small and so the figures for Plaid Cymru must be treated with a little more caution. While Liberal Democrat voters in Wales are very warm to Plaid Cymru, this is a little more muted among the Greens. When looking at Plaid voters though, the opposite is the case: around a third dislike the Liberal Democrats while a similar proportion like the Greens.

The Unite to Remain alliance has been born from a need to make the first past the post electoral system work for smaller parties and to maximise the chances of voters for these parties having significant representation in the next parliament. However, the analysis above highlights that despite the polarisation of politics around the leave and remain camps, there are distinct party loyalties among these and not all voters see remain parties as interchangeable. This will be important for trying to assess the impact at the constituency level where the obvious analytical choice of adding up the votes for all the parties in the pact and allocating them to the party standing there is likely to overestimate the chances of winning the seat.

________________

Paula Surridge is Senior Lecturer at the University of Bristol.

Paula Surridge is Senior Lecturer at the University of Bristol.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

1 Comments