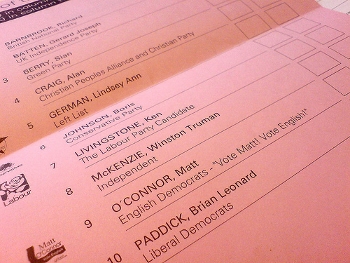

The government’s plans to change the voter registration system in the UK hit the headlines as it was revealed millions of voters could be ‘removed’ from the electoral register. Matthew Partridge argues that the changes, supposedly aimed at reducing fraud in the electoral system, could spark partisan registration drives, drive up the cost of politics and depress turnout.

The government’s plans to change the voter registration system in the UK hit the headlines as it was revealed millions of voters could be ‘removed’ from the electoral register. Matthew Partridge argues that the changes, supposedly aimed at reducing fraud in the electoral system, could spark partisan registration drives, drive up the cost of politics and depress turnout.

There is widespread agreement that the government’s proposals to move from semi-automatic household voting registration to a system where the onus is on individuals to proactively register (or in the case of those already on the electoral rolls, to re-register) will result in a dramatic fall in the number of those able to vote. The Electoral Reform Society estimates that if individual voter registration (IVR) goes ahead, the percentage of eligible voters registered will fall from the current figure of 90 per cent to 80 per cent by 2014.

The political impact of this move has been hotly debated. Mehdi Hasan of the New Statesman argues that it will lead to a decline in overall turnout, exacerbate the tendency of voting to be positively correlated with income and generally benefit the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives at the expense of Labour. The Telegraph’s Ed West, a supporter of the changes, counters that those are unwilling to register don’t deserve the vote and claims that the reforms will reduce fraud, especially in areas where the “head of the household” might put pressure on family members.

Citing cost restraints, the Electoral Commission has not yet carried out any research on the potential impact of these changes on the number of voters. However, the literature on the relationship between voter registration laws and overall turnout in America, where variation in registration laws from state to state make comparisons easier, suggests that making it more difficult to register depresses turnout, though by a proportionally smaller amount than the impact on registration suggests. This suggests that although many of those unwilling to register are also unwilling to vote, there are many who find registering more difficult than voting.

Ending semi-automatic voter registration will also change politics in other ways. Although some supporters of the reforms argue that shifting responsibility for registration from the state to the individual encourages parties to engage with voters through registration drives, this can be costly, driving up the costs of politics generally and increasing the importance of fundraising, along with the inevitable scandals and conflicts of interest. Partisan driven voter registration can be extremely selective, with demographic groups that are relatively uncommitted to one party ill-served. As one American political strategy guide puts it “Focus on registering likely supporters; a shopping mall may have lots of traffic but may not be a good place to register voters unless most of them may actually support your campaign”.

Although proponents of IVR claim that individual voting registration will curb fraud and reduce opportunities for intimidation, it may also increase the power of self-appointed community leaders, who will be able to leverage their ability to register large numbers of voters into real influence. It also needs to be pointed out the efforts of some voter registration groups in the US, such as the now defunct Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN), have been called into question after it was charged with filing thousands of fraudulent voter registration forms.

Even if these problems don’t occur, IVR will fundamentally change the nature of British politics. A political culture where the primary electoral task of parties is to appeal to a majority (or at least a plurality) is different to one where elections are decided on the ability to get relatively smaller numbers of supporters to turn up at the polling station. The political polarisation and gridlock in systems based around the latter, where groups of small partisans on each side dominate each party, can mean the interests of moderate voters are less well represented.

These “reforms” to the registration system seem aimed at skewing the electoral system in favour of the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, especially since they will be used to determine future constituency boundaries. If David Cameron is really concerned about fraud he would be better advised to stick with the current system and allow the Electoral Commission to access data from the NHS, Department of Work and Pensions and Inland Revenue to improve the electoral roll.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

The voting right is a fundamental right and voter registration is voluntary. The proposed improvement measures aim at preventing voter mistakes or fraud in order to protect the fairness and credibility of elections.

The US is one possible place to look to for lessons, but as its society and politics are so different from ours, I think lessons from there need to be taken with some caution.

There is also a possible source of lessons much closer to hand – namely Northern Ireland, which switched to individual registration several years ago. Politics hasn’t been transformed there in the way that you’re suggesting it would be in the rest of the UK. Of course, Northern Ireland is different in many ways but I think if you’re going to argue that the impact in the rest of the UK will be very different from what we’ve seen in Northern Ireland, there needs to be some case made as to why it will be so different?

I’m not sure that such a case can be made, and in fact therefore the Northern Ireland experience is evidence that individual registration won’t have a major impact on politics (though I think it is still a good move for the benefits it will bring).

But if you think Northern Ireland isn’t a good guide to what will happen in the rest of the UK, then I’m not at all sure why the US, which is (even more) different is a good guide?

Interesting piece, Matthew, and you are absolutely right to stress the risk that registration levels could fall quite sharply as a result of voluntary individual voter registration. You are also right with regard to the link with the rules for boundary changes and the possible partisan consequences – although I’m not sure why it would help the Lib Dems all that much.

I don’t quite follow some of your arguments, though. You suggest we could ‘stick with the current system and allow the Electoral Commission to access data from the NHS, Department of Work and Pensions and Inland Revenue to improve the electoral roll’. But it’s local Electoral Registration Officers who compile the electoral registers (there are hundreds of local registers, not a single national one), so I’m not sure why its the Electoral Commission who you suggest should have access to the other sources. And what would they do with that data? Check the identity of every voter? Look for potentially eligible electors who are missing from the registers? Wouldn’t that be pretty much the same as the proposals in the White Paper which, at least for the moment, suggests retaining the annual canvass and supplementing it with data-matching from other public databases?

I’m also not sure about the comparisions with the USA. True, the barriers to registering in some States does depress registration levels quite significantly and electoral registration drives are indeed highly partisan. But the proposed reforms for GB have more in common with those introduced in Canada and Australia in the 1990s or, more obviously, in Northern Ireland a decade ago. The one basis for comparison with the USA is not to do with IER, but that the USA is just about the only established democracy in which voter registration is entirely voluntary. The big question about the UK government’s draft Bill is whether under these proposal GB/UK would, or should, join the USA as one of very few democracies where voters have no legal requirement whatsoever to register. But that’s a totally different question from whether or not we should introduce IER.