With youth turnout having decreased dramatically over the past two decades, Laura Gardiner explains some of the drivers behind this change. She writes that, although housing insecurity may be driving young people away from engaging in the political process, it is precisely their vote that could precipitate meaningful change.

With youth turnout having decreased dramatically over the past two decades, Laura Gardiner explains some of the drivers behind this change. She writes that, although housing insecurity may be driving young people away from engaging in the political process, it is precisely their vote that could precipitate meaningful change.

We are days away from a General Election. Candidates will be shaking hands with as many potential voters as they can, aiming to win their support. But most will prioritise the bingo halls over the student unions because, as is well known, older people are much more likely to make it to polling booths. Cue the pop-narrative around the disaffection of youth, or the whims of the so-called ‘snowflake’ generation and their inability to put down their iPads for long enough to engage.

Except don’t, because that would be an inaccurate and superficial caricature of low voter turnout among the young that fails to recognise its advent, drivers or wider significance. Here (based on this longer briefing) we set out what’s happened to turnout across the generations, what’s driving these trends, and why they matter more than ever given the salience of intergenerational issues going into the 2017 General Election.

Changing youth turnout and the generational turnout gap

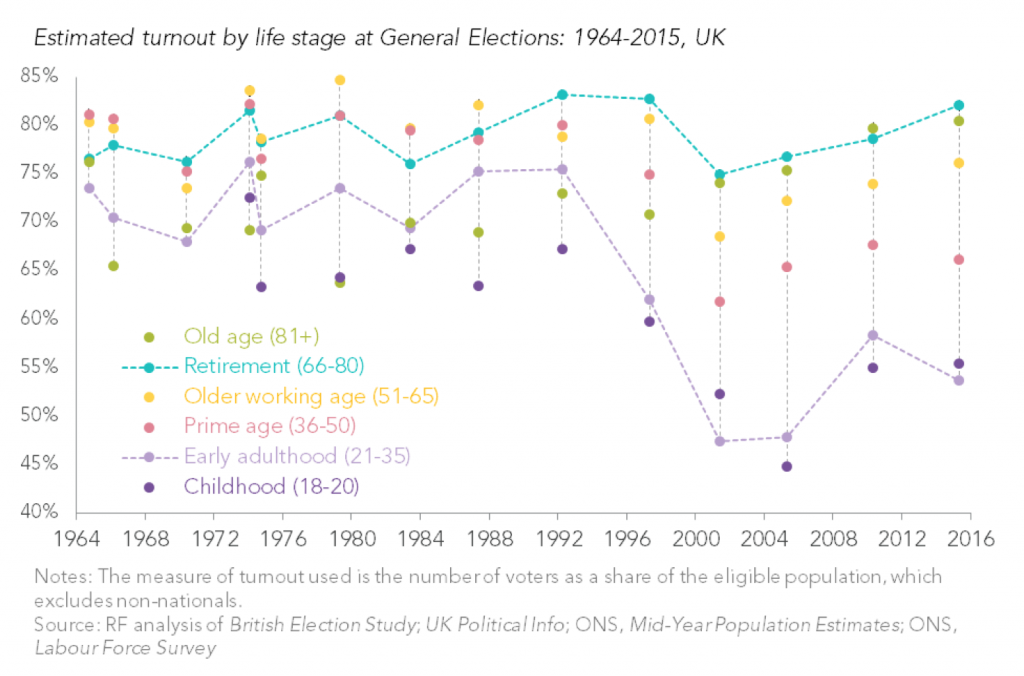

The first common misconception when it comes to voting likelihood across age groups is that it’s always been this way. In fact during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, young adults were only a little bit less likely to vote than those in older age groups. But this has fundamentally changed in the past two decades. The turnout gap between those aged 21-35 and those age 66-80 rose from 8% in 1992 to a peak of 29% in 2005, before falling marginally to 28% in 2015.

The widening of this gap coincides with the overall decline in turnout, suggesting that a large part of weakening democratic engagement overall is explained by young people’s behaviour in particular. And before we rush to judgement of today’s youth, the fact that this fall in turnout dates back to the mid-90s means that it was those now in their 40s who set this train in motion.

Because low youth turnout is a relatively recent phenomenon, comparing different birth cohorts at the same age shows very different patterns over the life course. Both generation X (born 1966-80) and the millennials (born 1981-2000 – our preferred term for the so-called snowflakes) have so far been around 20 percentage points less likely to vote in their late 20s than the baby boomers (born 1946-65) were when they were young. The majority of the gap endures when we control for the overall decline in turnout.

It’s worth noting too that a high voting likelihood isn’t the only thing that has boosted the democratic position of the baby boomers. As their name suggests, due to high birth numbers there are also quite a lot of them at any given age. To the extent that politicians respond to the broad priorities of different age groups or generations, the combination of high turnout and lots of peers has meant consistent democratic firepower for the boomers.

What’s driven the decline in voting among the young?

Lots of people jump straight to the apathy of youth as the dominant explanation for the turnout gap. And it’s true that this appears to be at least a correlating factor. The proportion of 21-35 year olds who care which party wins the election fell by one-quarter between 1992 and 2015, while the same proportion actually increased slightly for retirees.

But there are other drivers that are playing at least as important a role. One is the decline in voting when first eligible, and the simultaneous strengthening of the relationship between past and future turnout. In other words, young people are less likely to vote first time round, and this effect gets amplified because getting into the habit takes relatively longer than it did in the past. This is why some people think compulsory first-time voting is a promising policy option.

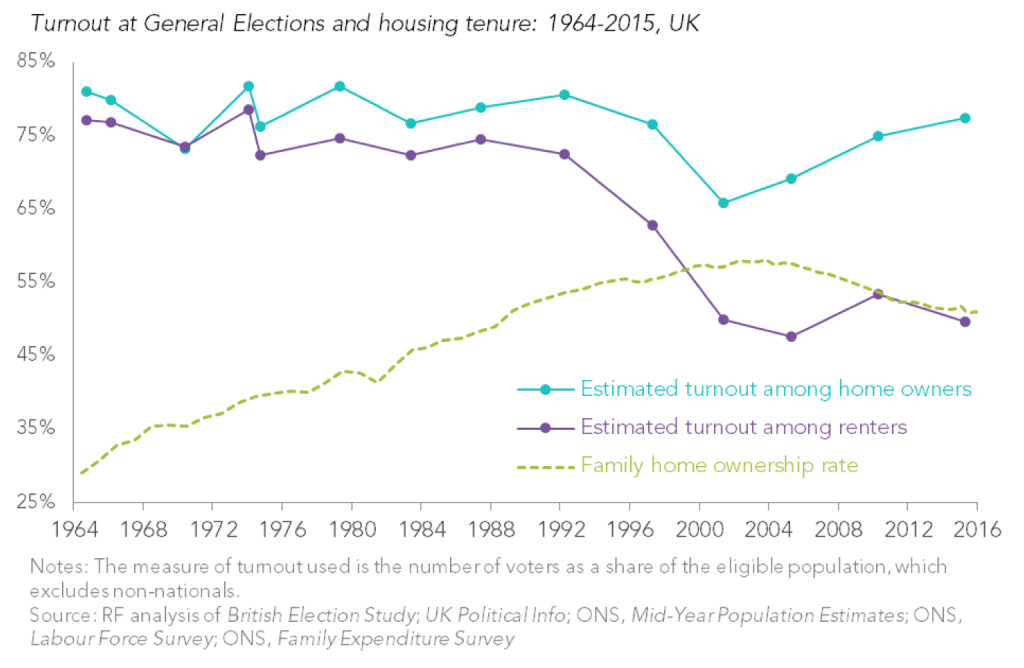

Perhaps the most striking driver of falling youth turnout, though, is the changing relationship between voting likelihood and housing tenure. The chart below shows that a gap has opened up between home owner and renter turnout since 1992, which we speculate is related to the shift from social to private renting and the increasingly transient nature of the latter. Electoral Commission analysis attests to this, suggesting that fewer than two in three private renters are even registered to vote.

With home ownership no longer rising overall, as the chart below also shows, this growing turnout-by-tenure gap is a big concern for wider democratic legitimacy. And with millennials half as likely to own in their 20s as baby boomers were, it’s not hard to see why youth turnout has been most deeply affected.

Why it matters – democratic firepower and intergenerational fairness

There’s an irony to the final point above. Housing is the area in which millennials are most obviously struggling compared to older generations, but their housing insecurity may be driving many of them away from engaging in a political process that could precipitate change.

The bigger picture here is that with millennials facing challenges in the jobs market, in building up assets, and in terms of what they can expect from the state, the intergenerational contract that underpins society shows signs of fraying. The hard task of addressing these issues will require public support, in order for democratically-elected politicians to pursue it. Politicians appeal and respond to the motivations of those who they expect to vote. This means we need to consider practical suggestions for maximising youth turnout, including automatic registrations, online voting, and better citizenship education.

But it also means we need to change the conversation, acknowledging that repairing the intergenerational contract matters to everyone – we all want the best for our children and our neighbours after all. That’s the task that the Resolution Foundation’s Intergenerational Commission is currently pursuing. The hope is that when we head to the polls next month and in future elections, politicians know we are voting not just for our own bank accounts but also for the legacy we leave to generations to come.

_______

Laura Gardiner is Senior Research and Policy Analyst at the Resolution Foundation.

Laura Gardiner is Senior Research and Policy Analyst at the Resolution Foundation.

Very interesting article but I don’t think it really answers the question of why young people aren’t voting at the same rates as they used to.Housing might be an increasingly important correlate but I’m struggling to see how this would actually affect young people’s motivation to vote rather than just have coincided with it. Is it that young people are more mobile so it is more difficult for them to stay registered? I doubt it’s as administrative as that. Have you thought of doing a comparison between examples of low millenial turnout (e.g. UK General Elections) and those with relatively higher turnout like the Scottish independence referendum or, as Pippa Norris above suggests, some countries with PR?

If housing tenure within a single member constituency is behind this age gap in the UK, then presumably there should be lower age gaps in PR systems with large DMs. Tested this cross-nationally?