Alan Manning writes that while the very richest have seen their incomes significantly pull away from those on low and middle incomes in the last 30 years, this has not been matched by a rise in the public’s desire to see incomes redistributed by government. While there is a significant public distrust for government interventionism in this area, we need to think harder about solutions to income inequalities.

Alan Manning writes that while the very richest have seen their incomes significantly pull away from those on low and middle incomes in the last 30 years, this has not been matched by a rise in the public’s desire to see incomes redistributed by government. While there is a significant public distrust for government interventionism in this area, we need to think harder about solutions to income inequalities.

When looking at major trends in the labour market, in the short to medium term, everything is dominated by the financial crisis and the public and private sector’s responses to it. But in the longer-run there are more powerful trends at work driven by innovation and globalization and there are distinct challenges and opportunities presented by these trends for the progressive agenda.

Inequality at work and wage outcomes

For many years, the main concern was about the quantity of work available. Although this is again a concern in the present recession, the focus has shifted in the past decade to the quality of jobs. If one looks at how the jobs in the economy are changing one sees rapid growth in the highest paid occupations (managerial and professional jobs), somewhat slower growth in the lowest-paid occupations (e.g. caring jobs) and declines in the middle occupations (skilled manufacturing and clerical jobs). A plausible explanation for these trends is that technology replaces human labour in tasks that can be routinized. This trend is often referred to as job polarisation. In addition it is clear that the demand for some types of labour are much more strongly affected than others by globalisation.

What are the consequences of this? First, in and of itself, it should not be regarded as a problem. Although these low-paid jobs are sometimes referred to as ‘lousy’, one should recognise the dignity of those involved in cleaning or caring and not fall into the trap of thinking that the people doing these jobs are less worthy of respect than others. The main way in which they are lousy jobs is because they are low-paid and the main problem caused by job polarisation is that it is a potential cause of rising inequality.

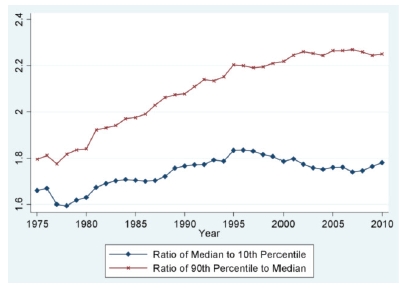

But here the outcomes have not been as bad as many have feared or allege. Figure 1 shows inequality in hourly earnings in the UK since 1975. Since the mid 1990s the lowest paid have made gains relative to the average, probably because of the job polarisation described above and the introduction of the National Minimum Wage in 1999. One should not exaggerate this: we still have more inequality at the bottom of the distribution than we had in the 1970s.

Figure 1: The Evolution of Wage Inequality in the UK, 1975-2010

Source: NES/ASHE

One might wonder, given the success of the National Minimum Wage, whether we should push on further by raising it substantially. The most common form of this argument is that we need a ‘living wage’, a requirement that all jobs pay an amount that can support a family, an argument that, in practice, boils down to the demand for a higher minimum wage. Campaigning organisations like London Citizens have done a fantastic job in persuading a sizeable number of employers to pay up. But, though wishing them well in their campaigns to persuade employers to sign up to the scheme, I would not support raising the minimum wage to the proposed living wage across the whole of the UK as I would be concerned that the proposed level of the minimum (£7.60 per hour) is more than the labour market could bear. It is an indictment of the free market that it cannot guarantee high enough earnings for everyone to have an acceptable standard of living but it is not a fact one can wish away. It should remain the job of the welfare system to provide adequate living standards for everyone in the economy.

The ‘rampant rich’ have pulled away from the rest

There is one other feature of Figure 1 that stands out: the rampant rich, how the highest earners have pulled away from the rest. In fact, Figure 1 only goes to the 90th percentile – the trends are much more dramatic if one looks at the 95th or 99th percentiles (see, for example Will Hutton’s Fair Pay Review). Before the crisis this rise in the earnings of the rich seemed to be tolerated by the ‘middle’ on some version of the ‘trickle-down’ principle – the average citizen seemed to be thinking that they were getting some share of the benefits accruing to the rich. But we now know that much of this was illusory, that a large part of the gains of the rich were at the expense of everyone else.

What is remarkable is how little impact the crisis seems to have had on the attitudes of the average citizen to the rich. Even Mervyn King, the governor of the Bank of England, expressed the view that “The price of this financial crisis is being borne by people who absolutely did not cause it,” and that “Now is the period when the cost is being paid, I’m surprised that the degree of public anger has not been greater than it has.” One can see this in social attitudes data. For almost 30 years the British Social Attitudes Survey has documented changing attitudes to many things including income inequality and redistribution. Figure 2 presents time series on the fraction of respondents who think “the income gap between rich and poor is too large” and who agree or strongly agree that “government should redistribute”.

Figure 2: Changing attitudes to Inequality and Redistribution

Source: British Social Attitudes

One notices the rise in pro-redistributive attitudes in the 1979-1997 Conservative government that may have contributed to the Blair landslide. One also notices the sharp fall to the lowest levels recorded of pro-redistributive attitudes during the 1997-2010 Labour government even though that government did not manage to reduce income gaps by very much if at all. Post-crisis there is a slight tick up but nothing very dramatic

It is also worth noting that though the fraction of the population thinking the income gap is too large is now much the same as in the early 1990s, the fraction thinking the government should redistribute is lower than then and close to an all-time low. This suggests that citizens no longer trust government to redistribute effectively even if they think income gaps are too large. This lack of trust in government is a major problem for the progressive agenda as redistribution does require government intervention.

It is the middle parts of the income distribution that are currently experiencing a large squeeze on their incomes through a combination of the recession and the longer-run trend of job polarization. It is this group’s votes that will likely determine the outcome of the next election. This is probably not the time to be pursuing policies that involve a redistribution from those with middling incomes to those with lower incomes. But it is a time to be pursuing redistribution from the highest-earners to those with middling and lower incomes. There are a number of forms this should take.

First, we need to become comfortable with. and robustly defend, a higher marginal rate of tax on the highest earners – the argument seems to be too readily accepted that higher marginal tax rates will cause the highest earners to work less hard. But that argument does not withstand scrutiny. Increase the marginal tax rate to 50 per cent and the hourly earnings of the top 10 per cent are only back to where they were in the mid 1990s. Because the top 1 per cent have seen much larger increases in incomes, a 50 per cent marginal tax rate still offers them higher hourly pay rates after tax than they had a decade ago. I seem to recall they thought it worth getting out of bed in the morning to go to work then. Perhaps they will all leave and go to Switzerland, but there seems to be some reports that a few that had gone are miserable and coming back to London.

Second, we need to think about ways to limit pay at the top. This is difficult but important. Difficult because I don’t think that rules like maximum pay ratios or maximum pay are workable. Either they will be set so high as to have no impact, or low enough to have some bite but to require exceptions. The pay distribution is much more spread out at the top than the bottom so a maximum wage is much more difficult to implement than a minimum wage. We also need to think about improved governance structures. But perhaps what needs to be done is to stir up some righteous indignation on the part of the population. The global elite like to argue their ever-increasing share of income is an inevitable result of ‘progress’ but it is not.

This article is a shorter version of one published in the Policy Network paper, Social Progress in the 21stCentury.

Please read our comments policy before posting.