Brexit has led to stronger powers for Westminster, a diminished role for international courts and the revocation of key legislation for the protection of human rights. Anna Sanders explains why all these factors are likely to have a profound and detrimental impact on gender equality in the UK.

This article is part of our series on policymaking in the UK after Brexit. For more analysis, visit the focus page.

The outcome of the EU referendum raised significant concerns among gender equality activists about the future of gender equality. Sam Smethers, then CEO of the Fawcett Soceity, warned that Brexit risked “turning back the clock on gender equality”. At the same time, Mary-Ann Stephenson, Director of the Women’s Budget Group, noted that “the overall impact of Brexit is likely to be negative…This will affect women as users, workers and consumers”. In our recent article, published in the Journal of European Public Policy, we ask: what does Brexit mean for the future of gender equality policy?

Which rights are at risk?

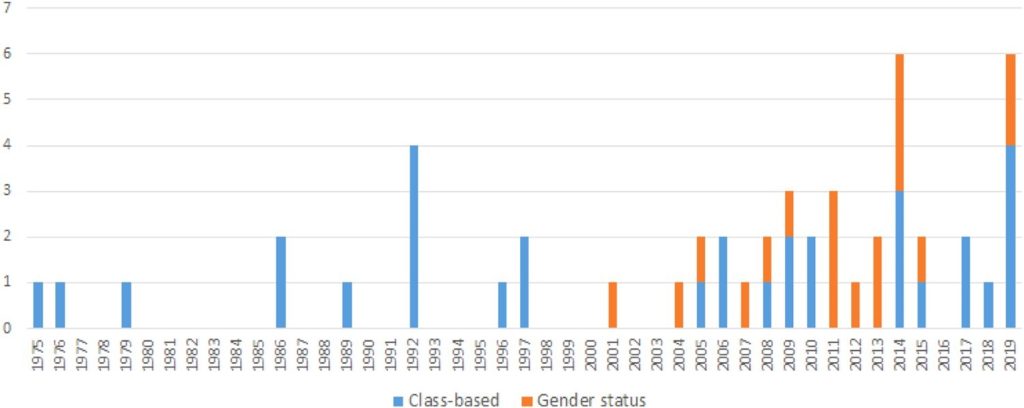

We examined UK government legislation, specifically directives that have originated from the EU between 1975-2019. We searched these directives using key terms relating to women and gender. We also classified these policies according to the type of gender inequality that they try to address. Women face a range of injustices: they often face discrimination on the grounds of their gender – through, for example, gendered violence or misogyny. They also face economic inequality as a result of the labour market, given that they are more likely than men to take time out of work to undertake care. Figure 1 below shows the number of directives aimed at addressing women’s rights between 1975 to 2019. Policies addressing women’s discrimination on the grounds of their gender are shown in orange, and those that address women’s economic inequality are shown in blue.

This illustrates how, historically, directives have addressed women’s economic inequality. Many of these directives relate to employment rights, such as strengthening employment rights for pregnant women in the workplace (the 1992 Pregnant Workers Directive) and setting minimum standards on parental leave (the 1996 Parental Leave Directive). Other directives include equal pay and strengthening employment rights for part-time and temporary workers – the majority of whom are women. The figure above also shows an increase in the scale and frequency of directives after 2004. Notably, the type of gender equality policies becomes more diverse, with directives increasingly addressing women’s discrimination based on their gender – such as those that tackle violence against women.

Yet the impact of Brexit risks directly rolling back these gains. In our article, we note that the governing structure of Westminster, which tends to be closed, masculinised and “power hoarding”, marginalises women’s interests and voices.

Why greater centralisation can be harmful to gender equality

The process of Brexit has seen a repatriation of powers to Westminster that has served to strengthen the government further. This is perhaps seen most clearly in the EU Withdrawal Act, which allows Ministers to amend, repeal or modify EU legislation converted into domestic law – often at the expense of parliamentary scrutiny. Since Brexit, Westminster has also repeatedly flexed its constitutional muscles to bypass sub-national governments which have, generally, taken more “women-friendly” approaches in their policymaking.

Westminster’s power was evident in its decision to override the Scottish Parliament’s refusal to grant consent to the 2018 Withdrawal Bill. Yet it was the issue of transgender rights which saw Westminster’s supremacy continue after Brexit. 2023 saw Westminster’s use of a “Section 35” order to effectively block the Scottish Parliament’s Gender Recognition Bill, which aimed to make it easier for transgender people in Scotland to self-identify. The intervention marked the first ever use of a Section 35 from Westminster since the creation of the Scottish Parliament.

Losing safeguards

Women’s rights also risk being rolled back through a reduced role of international and national courts on UK equality law. Historically, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) has played a key role in protecting women’s rights. Britain’s withdrawal from the EU has meant that national courts can no longer refer matters to the ECJ, and any future ECJ case law will no longer be binding on UK courts. UK courts may consider the rulings of the ECJ but depart from a previous decision “when they consider it appropriate to do so”. As such, there is uncertainty around which aspects of women’s rights will remain.

Since Brexit, there has been evidence of women’s interest groups losing access to the policymaking sphere.

Whether national courts will protect women’s rights will, in part, depend on the ability of interest groups to push for gender equality reform. Previously, women’s interest groups have been relatively successful at lobbying the EU to advance women’s interests at the international level. Yet since Brexit, there has been evidence of women’s interest groups losing access to the policymaking sphere, where achieving change at the national level has become increasingly difficult. This was seen through, for example, the House of Commons Procedure Committee review, which recommended that MPs should not be allowed to bring their babies into Parliament. The outcome of the review came under criticism as it emerged that the Committee had not consulted with anybody outside of Parliament – despite being encouraged to do so.

Women bear the brunt of the economic downturn

There is also the long-term economic impact of Brexit itself. The Office for Budget Responsibility has estimated that the economic effects of Brexit will reduce productivity by 4 per cent by the first quarter of 2025. This is set against a backdrop of what the Institute for Fiscal Studies describes as “the most severe economic downturn in centuries” following the global COVID-19 pandemic, the cost-of-living crisis, and subsequent austerity measures pursued after the 2008 global financial crisis. Research has shown that in periods of economic downturn not only do women bear a heavier burden than men, but costly economic policies are much less likely to be adopted by governments.

The mantra of the Leave campaign was all about restoring parliamentary sovereignty and “taking back control”. But a further shifting of power to Westminster will likely come at women’s expense. There are, of course, normative implications of this: the policy process should take into account the needs of both men and women. But governments should be mindful that there are also electoral implications. Women comprise the majority of the British electorate, meaning that the average voter is a woman. Governments that overlook the interests of women may therefore find there are electoral costs to pay.

This post draws on the article “The direction of gender equality policy in Britain post-Brexit: towards a masculinised Westminster model” (Journal of European Public Policy, 2023) by Anna Sanders and Joanna Flavell.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by William Fortunato via Unsplash.