A political party’s youth faction is a channel for engagement but can also provide a glimpse into what parties might look like in the near future, writes Emily Rainsford. She explains what we know about these factions so far, and why it’s worrying.

A political party’s youth faction is a channel for engagement but can also provide a glimpse into what parties might look like in the near future, writes Emily Rainsford. She explains what we know about these factions so far, and why it’s worrying.

Young people are not known for joining political parties. But recent developments in the Labour Party and the Scottish Nationalist Party, even if exact numbers are hard to get by and assess properly, suggest that parties are becoming more popular among young people. In my recent article (open access) I find out who they are, why they get involved, and what they think about politics.

What do we know about political parties’ youth factions?

The simple answer is we don’t know much about them. What we do know is that they have a complicated relationship to their ‘mother’ party. At first glance, there seems to be a close relationship because the youth faction shares the name, and sometimes get resources and seats on the executive of the main party. Many parties do make concerted efforts to include young people in policy formation as well. But research has shown that despite this, youth factions are marginalised and have very limited influence in the party.

Youth factions also socialise young people for future engagement. One of their main purpose is to recruit members and as such are an opportunity for young people to channel their political enthusiasm. But research shows that many politicians have a background in the youth wing of their party. Understanding these factions is therefore very important in understanding what the future of political parties might look like.

Who are the members?

Studying youth factions presents methodological challenges, in that members are hidden under main party membership in general population surveys. Instead, I went to their events and distributed a survey there, using the contextualised survey method developed by Caught in the Act to get an even distribution and avoid interviewer bias. Importantly, this means that the research is specifically referring to the active members of the youth factions, not the whole youth faction.

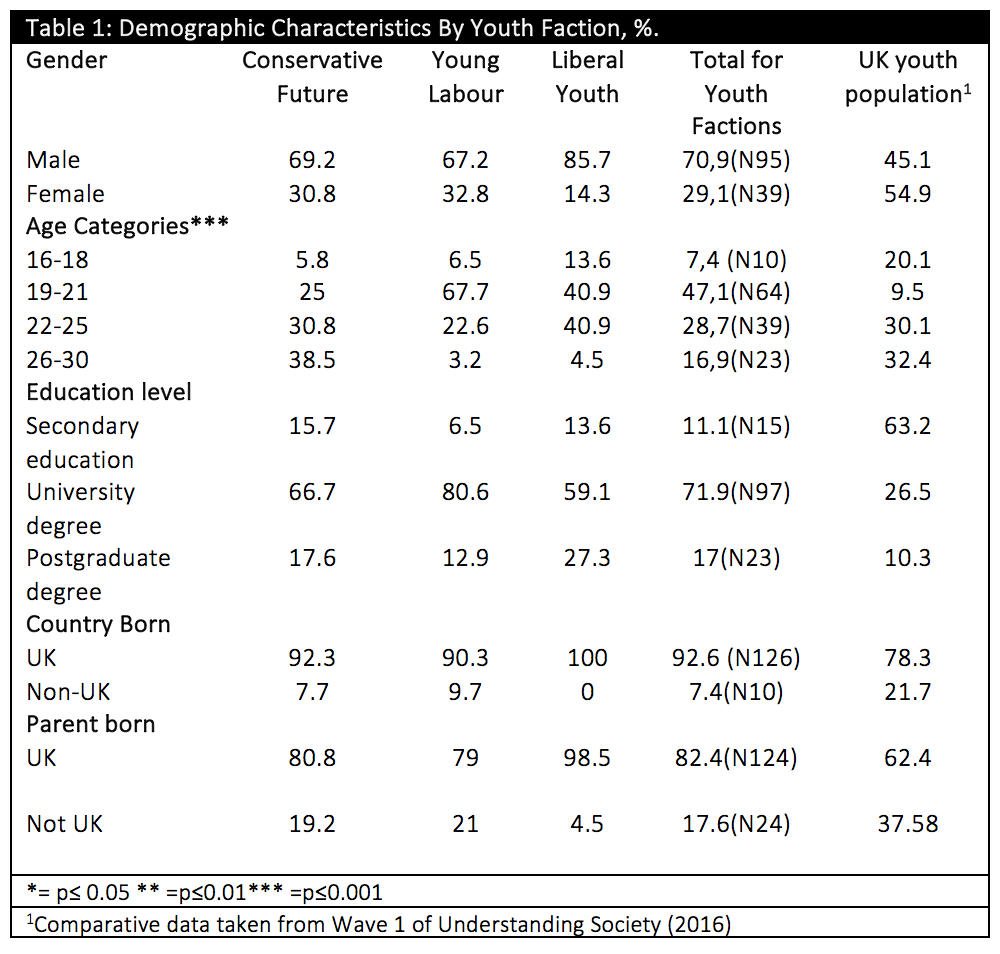

No one would expect that those who are active members would be demographically representative of the rest of the population. Yet what we see in Table 1 below is still concerning. The youth faction activists are male, pale, highly educated and identify as middle class. This composition, across the parties, paints a bleak picture of how well women and minorities are represented in youth factions.

This analysis also reveals a bigger issue regarding the diversity of not only the youth factions, but of the political parties themselves. Because the factions fulfil a socialisation function, it becomes evident that the lack of diversity at mother party level starts in the youth factions. There is a real challenge here for the parties as well as the youth factions to improve the diversity in the latter to potentially have a spill over effect on the mother party.

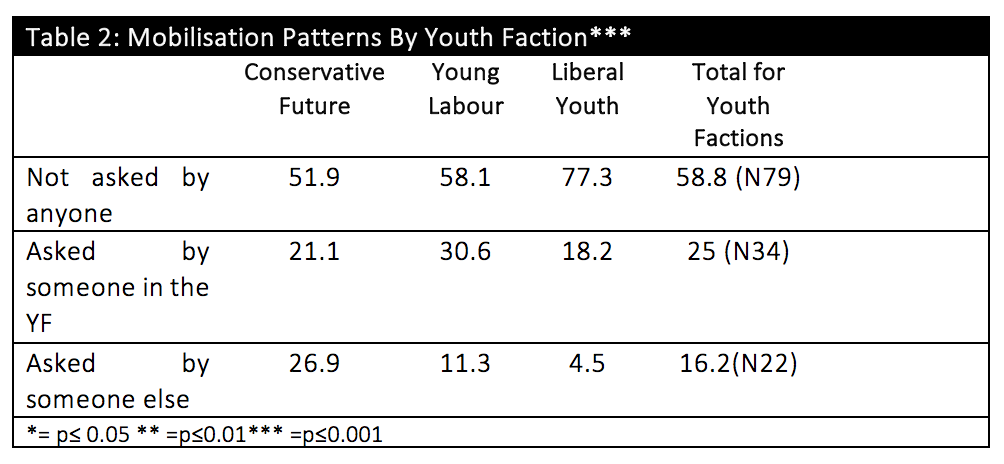

Being asked to come along to political events is one of the strongest predictors to why someone turns up. It is therefore surprising that in Table 2 we see that the youth faction activists are very unlikely to have been asked to come along. It might be that they are just very motivated people, who love going to political events. It isn’t necessarily a bad thing to have driven people who are interested in politics being engaged, and possibly move in to the political parties. Even if this is true, the results are an indication of a quite isolationist behaviour of the youth factions.

Being asked to come along to political events is one of the strongest predictors to why someone turns up. It is therefore surprising that in Table 2 we see that the youth faction activists are very unlikely to have been asked to come along. It might be that they are just very motivated people, who love going to political events. It isn’t necessarily a bad thing to have driven people who are interested in politics being engaged, and possibly move in to the political parties. Even if this is true, the results are an indication of a quite isolationist behaviour of the youth factions.

Yet it doesn’t seem to be true that a political career is what motivates them to attend. The analysis of the motivations and political attitudes of the young party activists showed that they were mainly motivated by the opportunity to expressing their views and defending their interests. The motivations to stand for election or work in politics – the more careerist ones – gained the least support in the analysis. It is possible that the careerist answers were not considered to be socially acceptable – it’s not cool to say you want to stand for election. But the fact that the more neutral motivation ‘work in politics in the future’ got similarly low support suggest that those instrumental motivations really aren’t part of the reasons young people get involved in politics this way. They get involved to change things, pressure politicians, and express their views. These are not the motivations that have been associated with active membership in a political party.

The young activists don’t seem very committed to the party either. Whilst they rate very highly on their sense that they can achieve things, they don’t think the youth faction is the only way for them to ‘influence the situation of young people’ nor ‘for young people to make their voices heard’. The exception is Liberal Youth, who are more likely to agree the youth faction is the only way to influence things, unlike their counterparts in Conservative Future and Young Labour.

What these results suggest though is that to young activists, political empowerment is not limited to the political party or the youth faction. Instead, they see many other avenues and pathways to make their voices heard. The power lies in them, not the organisation. The parties therefore have to be careful not to lose these active young people to other organisations.

What does the future look like?

If the members surveyed here continue their engagement, it looks like the parties in the future will continue to be male and pale. But it is not certain that all these members will continue. These activists must be highly motivated to have turned up without being asked, and we want those kind of people in politics. We want those who care. But they don’t think this is the only way to be political, not even the most effective way to make their voices heard.

So, if political parties do not hone this energy and self-motivation and listen to their young members, it is very likely that they will move their engagement elsewhere. This challenge is perhaps particularly pertinent for Labour, as the claims are that the surge in their membership mainly comes from young people. Labour therefore needs to make sure that their new, enthusiastic, powerful young members get the opportunity to be heard. Youth faction activists cannot be taken for granted.

______

Note: the above is based on the author’s article, published in Parliamentary Affairs.

Emily Rainsford is Research Associate at the University of Newcastle.

Emily Rainsford is Research Associate at the University of Newcastle.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay/Public Domain.

1 Comments