Robert Crowcroft examines how the Conservative party conceptualized the problem of ‘the future’ in the run up to the 1945 election, and explains that their message was bleak, especially compared to that of Labour. He writes that, irrespective of the validity of those assessments, the 1945 contest raises broader questions about what the public is prepared to hear during elections.

Robert Crowcroft examines how the Conservative party conceptualized the problem of ‘the future’ in the run up to the 1945 election, and explains that their message was bleak, especially compared to that of Labour. He writes that, irrespective of the validity of those assessments, the 1945 contest raises broader questions about what the public is prepared to hear during elections.

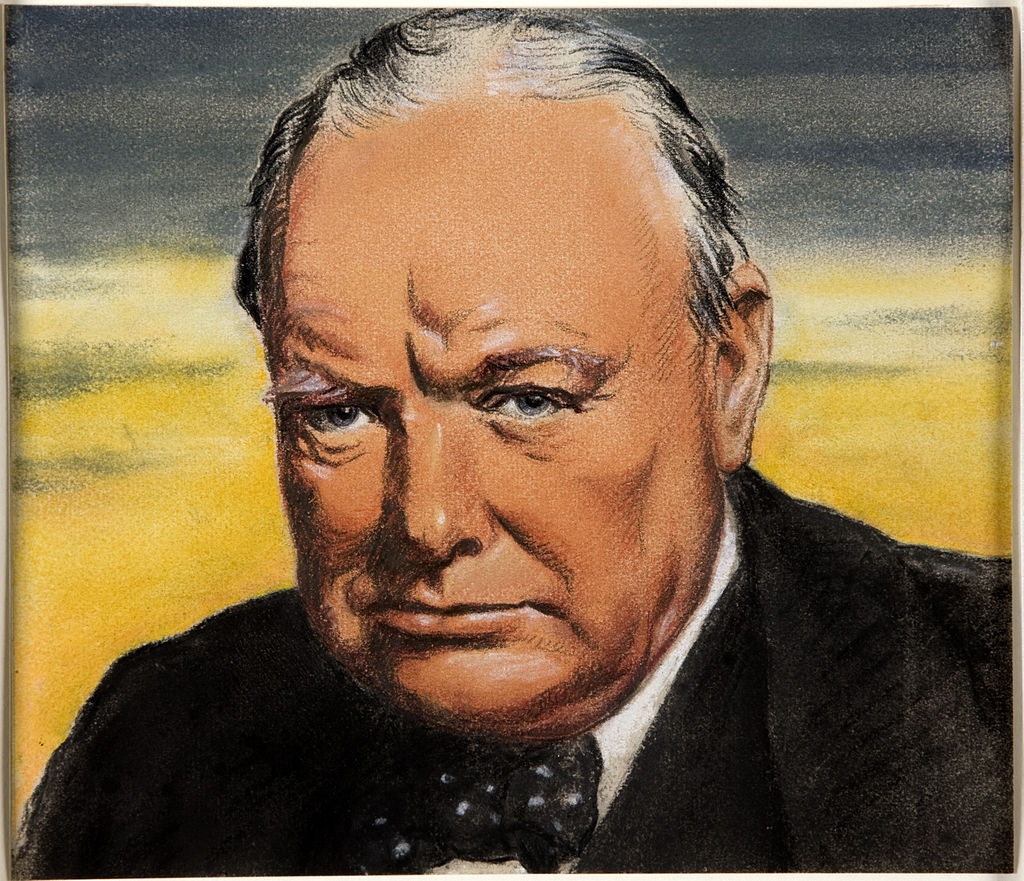

The British general election of July 1945 produced one of the most striking results in modern electoral history. The Conservative party suffered a landslide defeat at the hands of the Labour party; even the popularity of Winston Churchill could do little to arrest the scale of Conservative failure. There has often been a suspicion that this defeat flowed from the complacency of a Conservative leadership confident that Churchill would romp home to victory and unwilling to recognise that the public favoured bold new departures in social policy. There is truth to this, but the reality is also more complicated.

Between 1943 and 1945, senior Conservatives in fact invested tremendous energy in planning for the end of the war. To this end they attempted, in Churchill’s striking phrase, to peer into ‘the mists of the future’ and ascertain the nature of the post-war world. Men like Churchill and Sir Kingsley Wood, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, acted as futurologists and sought to predict developments. In July 1945, they presented their findings to the public – and were trounced at the polls.

So what exactly did Conservative leaders see when they looked into the future? They were convinced that the post-war years would be defined by hardship and danger. Huge debts had been incurred during the war, and it would take a long time to reignite British trade. There would be shortages and social misery. In this context, it was simply unrealistic to pledge unequivocal support for Sir William Beveridge’s landmark blueprint for an expansion of social services. The Beveridge report of late 1942 had captured the public imagination, presenting a vision of a better tomorrow including the establishment of a universal health service and expanded benefits; and the Labour party’s decision to align itself with Beveridge helped to sweep it to power in 1945.

But, sitting in his office at the Treasury, Wood was convinced that Beveridge was being naïve about the post-war financial position. He did not see how the Beveridge reforms could possibly be affordable at the same time as rebuilding British trade, the lifeblood of the country. It is also important to remember that nobody knew when the war would end. In 1943 it was believed that, even once Germany was defeated, it would take another two years to subdue Japan; it was calculated that the war would finally end in 1948. (The sudden effect of the nuclear weapons dropped on Japan in 1945 was impossible to foresee.) As such, making promises about post-war welfare measures that were still many years away from implementation seemed slightly surreal.

Wood thus thought it prudent to wait and see how Britain’s economy fared once peace returned before entering into binding commitments. ‘The time for declaring a dividend on the profits of the Golden Age’ was, the Chancellor argued, ‘when those profits have been realised in fact, not merely in imagination’. And as for those who wanted the Beveridge reforms implemented even while the war continued, Wood and Churchill were scathing: it was constitutionally inappropriate to commit future generations of taxpayers to a huge, and permanent, liability without holding a general election.

In Churchill’s mind, an even bigger problem than the scarcity of money was the global instability that would prevail once the Axis powers were defeated. This would be a dangerous world in which Britain would bear many burdens. He believed the priority would be for Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union to permanently ‘garrison’ the ‘guilty countries’ in order to deter any renewal of German and Japanese aggression. The costs of maintaining armed forces large enough to do this would be enormous. The task of rebuilding Europe would, Churchill warned, be a ‘stupendous business’. He felt oppressed by ‘the shadows of victory’. After the war ‘we should be weak, we should have no money and no strength’.

In Churchill’s mind, an even bigger problem than the scarcity of money was the global instability that would prevail once the Axis powers were defeated. This would be a dangerous world in which Britain would bear many burdens. He believed the priority would be for Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union to permanently ‘garrison’ the ‘guilty countries’ in order to deter any renewal of German and Japanese aggression. The costs of maintaining armed forces large enough to do this would be enormous. The task of rebuilding Europe would, Churchill warned, be a ‘stupendous business’. He felt oppressed by ‘the shadows of victory’. After the war ‘we should be weak, we should have no money and no strength’.

His greatest fear was that a major new conflict would erupt. The Prime Minister worried about the possibility of war with the Soviet Union, and had been pondering this since the summer of 1944. He remarked that once Germany was defeated, ‘what will lie between the white snows of Russia and the white cliffs of Dover?’ He asked his generals to devise plans for a Soviet attack on western Europe and the outbreak of a conflict that would see Britain and the United States ally with Germany. By early 1945, much of Churchill’s day-to-day business was consumed with the threat of the Red Army and its local proxies in a power vacuum. The ‘enormous Muscovite advance’ needed to be resisted, for it was ‘sweeping forward…on a front of 300 or 400 miles’. He believed that there was ‘very little’ prospect of averting a new World War, and claimed to be more fearful about the international situation than even in the late 1930s. This was a nightmarish vision of war without end, and Churchill believed that such a conflict might soon be forced upon Britain.

Far from not thinking ahead, as some have suspected, the Conservatives had clearly spent much time pondering the future. Ahead of the July 1945 general election, the party leaders presented these prognostications to the country. The first three section of the Conservative manifesto dealt with defence and strategic issues, reinforcing the primacy of foreign policy in Churchill’s mind. It also pledged to expand the social services with measures comparable to those Labour was outlining; but whereas Labour presented a positive vision for immediate action, Churchill’s party outlined a more incremental approach.

The Conservative message was a bleak one. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it did not win the support of the electorate. Churchill feared that the public were being seduced into believing that ‘Eldorado’ lay just around the corner, and attempted to be frank with the country about the challenges he believed that it faced. The result was an electoral disaster. Irrespective of the conclusions we may draw about the validity of Churchill’s specific assessments, there is an important question here: in the cut-and-thrust of democratic elections, can the public bear to hear grave tidings?

_____

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in Historical Research. (DOI: )

Robert Crowcroft is a Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Edinburgh.

Robert Crowcroft is a Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Edinburgh.

The Conservative-led wartime Coalition obviously started making plans for social reforms during the war: a social security system designed by the Liberal Beveridge; a National Health Service designed by Labour’s Bevan; an education system designed by the Conservative Butler. Three pieces of progressive social legislation.

So in which of these reforms would a future Conservative government—no longer in coalition after wining the 1945 election—be interested?

Look at the answer to this from the viewpoint of a millionaire. He doesn’t need social security, money is the least of his problems. Nor does he need a health service: he’s can easily pay for private health care.

What he does need though is an educated work-force: his companies can then be made much more efficient (and profitable).

The war had demonstrated this forcefully. In 1938, 88% of all school leavers were 14 years old. When the war came with its enormous demand for Service people like pilots, navigators, marine engineers or civilians for radar work the British education system—which wasn’t important enough to have its own Ministry; it was merely a Board—was found wanting.

Industrial-scale IQ testing of millions of male and female conscripts was rushed-in to identify talent which could then be trained for high-skilled war work. The results of this testing showed that a vast pool of unused talent was out there and needed educating. It was good for the war effort and it would be good for re-building the country after the war. Hence the 1944 Education Act, the only one of the three pieces of progressive social legislation to be passed during the war itself. And it’s undeniably true that an educated Army, Navy and, especially, Air Force had helped win the war, as had an educated work-force.

But were the Conservatives only going to give the people one out of three? “You can have education, but not social security and not health”. It would seem from the election result that this is exactly what the people thought.

I’m not old enough to remember WW2; I have to rely on my father’s war stories for what it was like at the grassroots level. “There’s what’s going on as reported by the newspapers, and then there’s what’s REALLY going on”.

It would seem that people were well aware that:

Massive profits were being made by companies which, say, made aircraft, made army uniforms, built ships etc.

Massive profits were being made by the private railway companies inundated with mass travel on wartime business and travellers could actually see the profits being made. Rail nationalisation by Atlee’s government after the war was a popular move.

Massive profits were not being made however by millions of service personnel.

The war involved a sudden and massive adjustment in the relationship between the upper class and the lower-orders. The former (small in number) needed the latter (large in number) to work in their factories (and make them massive profits) and put on uniforms (and fight their battles). I’m exaggerating to make my point but it’s a valid one. Films in the same vein as “Millions like us”—daring to show friction between conscripted workers from different social classes—needed to be made to encourage the “we’re all in it together” spirit.

The bitterness between the classes that had festered since “the boys came home from Flanders” never boiled over into major civil unrest but for the lower-orders, WW2 brought them a muted form of payback both during the war and in the 1945 election result.

I was just about to make the obvious comparisons that Arthur Murray has just done as so most of what I would have said has already been said.

Those people lived through the 1920s, my own father told me of his observations of children going to school without shoes, he saw that himself, he did not need to be told what the Tories promise and what one actually gets are two entirely different things.

The land fit for heroes did not match the rhetoric, serviceman were fighting for their own salvation which they achieved, even though the Tories won it back during the 50s and early 60s they saw growth in the mixed economy that we can only dream of today. So it made economic sense as well as the improved well-being.

Neo-Classical economics has been replaced by Neo-Liberalism which has driven us back to 1920s, only a return to socialist ideals will even save what is left of capitalism here today, Capitalism is devouring itself and unless society intervenes it can’t survive.

Arthur Murrays’s comment was very interesting and on the mark. Meanwhile back in the sticks the electoral registers and boundaries were on the rough and ready side, unsurprisingly. My experience at the time was that there was a perverse belief. Very many assumed Churchill would win, a consequence of which was that a lot of new voters, an unusually high proportion then, and others, gave a sympathy vote to Labour mindful of the work done by Attlee, Bevin etc. during the war. I was on an Army General Staff in the mid 50’s in Germany and Churchill’s fears were all too real and right. In July 1945 it was the Desert Rats, the 7th Armoured Division who did the British part of the Allied Berlin Victory Parade. A kind of “watch it mate” statement.

The public can bear to hear grave tidings, the remain campaign was nothing but project fear assumptions of doom and gloom if we voted leave and Utopia if we remained, and yet a majority chose the leave option. It is reality over fiction that sometimes wins through, as in 1945 when labour were more realistic than Churchills vision of needing to keep an over manned military.

In the early 1940’s as the Army re-grouped after the Dunkirk evacuation Churchill, who had been impressed by the vigour with which the German Army had performed in Norway and in France, was keen to introduce measures to increase the motivation of the British infantryman.

It was decided that British service personnel were to be given lecture courses in current affairs organised, in the case of the army, by the Army Bureau of Current Affairs (ABCA).

So what sort of politics will interest men who one day are going to run up a beach under a hail of machine-gun fire?

Do you say something like “After the war we are going to implement the Beveridge report and its proposals for a strong social security system. The Butler Act will widen access to education. A National Health Service will be introduced. Europe’s nations will come closer together to prevent another war” ?

Or do you sing the praises of the 1930’s ? “Low wages, weak unions, hire and fire on a whim, patchy healthcare/education. We’ll keep Europe balkanised to encourage nationalism…”

For the ABCA lecturers it was a no-brainer. Anyway it was what the soldiers wanted to discuss in their current affairs lectures. My father, a trade union activist and a wartime conscript, told me how much he liked ABCA lectures.

It had never happened before: millions being exposed to ideas of social justice and international co-operation coming from the authority figures of ABCA. The many Conservative newspapers of the 1930’s had never publicised ideas like that; they were far too dangerous.

Conservative MP’s quickly began howling at the content of the Army’s political debates. Maurice Petherick MP wrote to Chuchill’s PPS: “I am more and more suspicious of the way this lecturing racket is run…for the love of Mike do something about it, unless you want to have the creatures coming back all pansy-pink.”

It made no difference: too many WW2 servicemen were being told by their fathers “We were told we were coming back to a land fit for heroes to live in. It didn’t happen. Don’t let the Tories screw you like they did to us after WW1”. And too many service personnel were telling their families the same thing. The whole country—and its voters—was being educated.

After the war though when the lectures were long forgotten and Labour said that a biassed British press gave the Tories a massive advantage, the Tories—their howls over a biassed ABCA also long forgotten—accused them of patronising an electorate who were well able to make up their own mind without the help of newspapers. Nevertheless, it looks as if newspapers play a very important role in persuading voters to accept hardship: short-term pain for long-term gain.