Are petitions a valuable democratic tool or do they simply amplify the views of those who are already politically engaged? Drawing on a new study, Cristina Leston-Bandeira and Blagovesta Tacheva explain why participatory tools such as petitions must be integrated with communication and education frameworks to ensure they reach underrepresented groups.

Petitions are a popular avenue for participating in politics, with a recent study finding that signing a petition is the dominant form of political engagement. Thanks to new parliamentary processes introduced in recent years, petitioning parliament has also become an effective way for the public to raise issues of concern to policymakers.

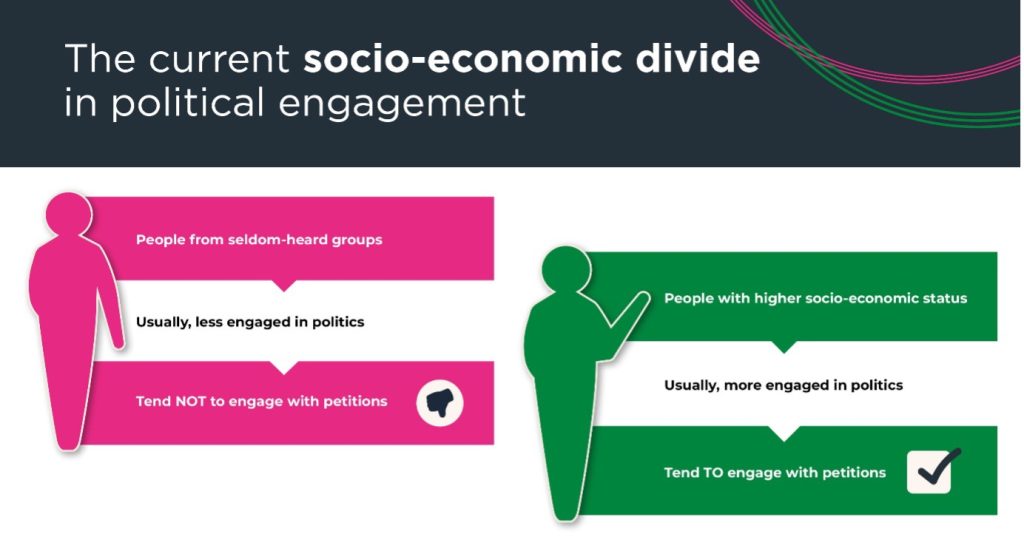

However, as illustrated in the figure below, current petitioners are overwhelmingly from already politically engaged groups, typically an older white public with high socio-economic status – the so-called “usual suspects”. Rather than expanding opportunities for democratic engagement, there is a risk that petitions to parliament are simply amplifying the voices of those who “already shout the loudest”. Source: Research Retold

Source: Research Retold

This problem is compounded by a lack of research on how people from disengaged groups perceive engagement and petitioning. In a new study, we addressed this issue by asking people from seldom-heard groups, such as those from a low socio-economic or ethnic minority background, for their perceptions about petitioning. Our aim was to identify the barriers and enablers to engagement faced by groups beyond the usual suspects.

To do so, we organised focus groups with petitioners and non-petitioners, including people from seldom-heard groups. This was supplemented by interviews with parliamentary officials and representatives from community organisations. This research allowed us to identify six core findings.

1. Deep mistrust

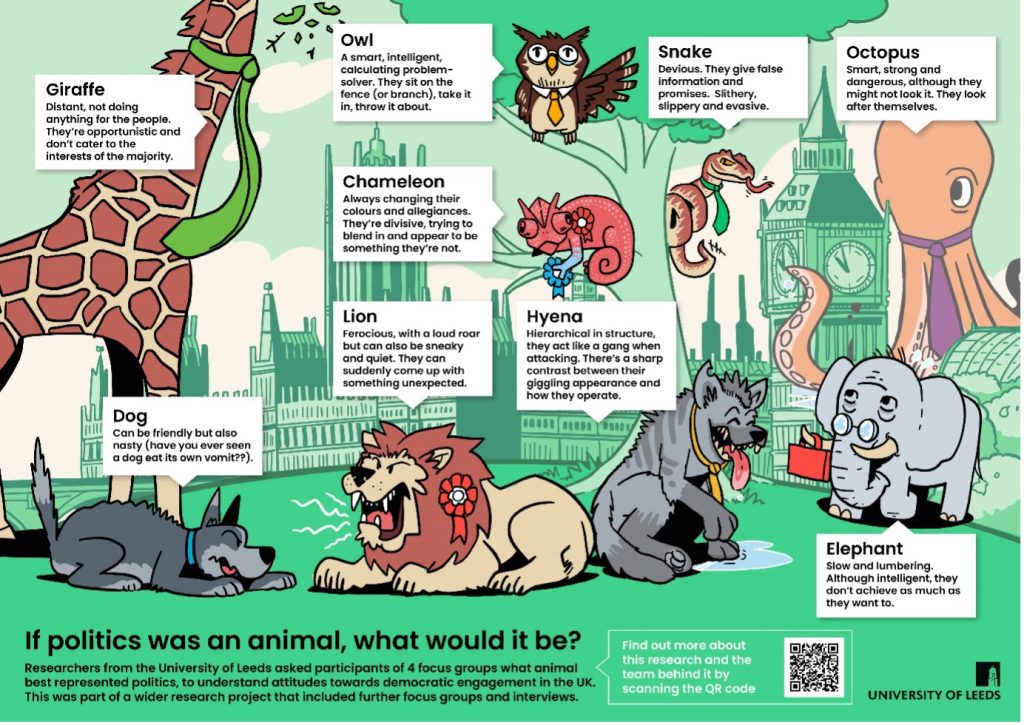

Unsurprisingly, our research unveiled deep mistrust of politics – as illustrated in the figure below, which shows participants’ views when asked what politics would be if it were an animal.

Source: Nifty Fox

Source: Nifty Fox

There was a particularly acute disconnect from the political system among seldom-heard groups. Although everyone who took part in the research identified core issues they felt strongly about, they did not see these issues as being related to politics.

Participants held such negative perceptions that positive experiences with politicians did not alter these perceptions. This affected participants’ willingness to engage in politics and petitioning. As a result, they did not view politics as a route for addressing core issues affecting them. Participants felt politics was not for them, despite expressing interest in it.

Our research showed that engagement with politics or political processes, such as petitioning, needs to be communicated through issues (examples, case studies, stories) as much as possible. This is what enables a connection between politics and citizens. We also found evidence that the deep well of distrust keeps people away from opportunities such as petitions.

2. A lack of awareness

Seldom-heard groups had limited knowledge or awareness of petitioning in general, including through platforms such as change.org. Very few were aware that they can petition their parliament. Those participants aware of petitioning were usually those who reported higher levels of political engagement overall. However, even the politically engaged non-petitioners were mostly unaware of petitions to their parliament, only knowing of websites such as change.org.

3. Obstacles to engagement

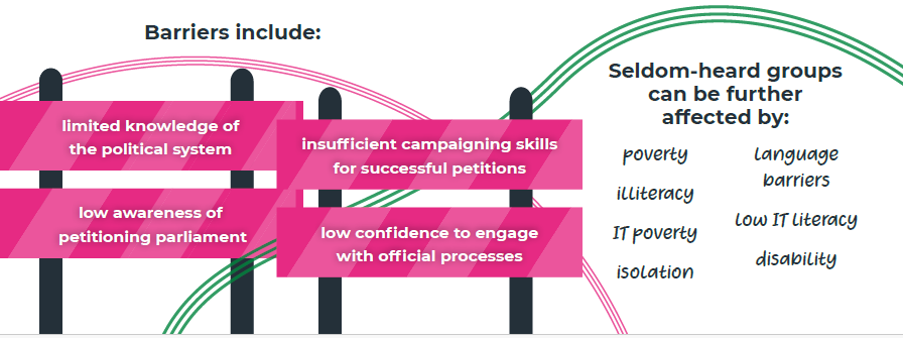

Seldom-heard groups are often affected by intersecting inequalities. These inequalities can exacerbate each other, making it extremely difficult for people within these groups to engage in politics. As illustrated in the figure below, seldom-heard groups can be affected by illiteracy, language barriers, low IT literacy, a lack of IT equipment, disability, poverty and isolation. These barriers can preclude them from engaging in formal politics.

Our research also identified specific barriers to political engagement and petitioning, such as limited knowledge about politics. This was a recurring theme throughout our research, with participants lacking basic knowledge about politics and the UK political system, such as an understanding of what parliament does and how it differs from the government. Source: Research Retold

Source: Research Retold

This was combined with a lack of key campaigning skills, as well as a lack of confidence, which can make the process of petitioning feel intimidating. These findings show why parliaments need to be more proactive in the way they disseminate and explain their petition systems if they wish to reach beyond the usual suspects.

4. Community organisations as mediators

Our research also showed the importance of community organisations working with seldom-heard groups as mediators when it comes to facilitating access. Community organisations have often built long-term relationships with these communities, they have direct access to them, they have a good understanding of their circumstances and challenges, and they have gained their trust. They could therefore play a role in helping to raise awareness of petitioning among these groups and even help them to start a petition, just as they help people access other services.

However, these types of organisations would not necessarily think of facilitating engagement with petitions, as they may themselves be unaware or unconvinced of their value. This was apparent in our interviews. Facilitating further involvement from these groups would also be challenging for community organisations due to a lack of capacity and resources.

Still, interviewees suggested that a buddy system in which engagement “champions” are identified could make this role easier. Following the “train the trainer” principle, these champions could be based in community organisations and trained to have a better understanding of petitioning and their potential role in supporting service users.

5. Managing expectations and guiding participation

Managing expectations was a recurring theme in our research. This is closely linked to the way parliaments’ e-petitions systems are communicated to the public. The language used to communicate with petitioners and explain the petitions process was often seen as unclear, with many asking for more plain language to be used.

Although petitioners were happy overall with their experience, a few found the process disjointed and unclear. These concerns were well summarised by one petitioner, who highlighted that clarity around the process and the language used to describe it is key for managing petitioners’ expectations: “You’ve got to have that clarity, otherwise people’s expectations go up here and they’re just going to be massively deflated by the end of it.”

The language used across all communication channels is essential to making the process more accessible beyond the usual suspects. This should be accompanied by the development of resources aimed at wider audiences, such as infographics, audiovisual material and “Easy Read” guides.

6. Collaboration with citizen-centred services

Finally, our research showed that petitioning processes cannot be considered solely through the actions of the officials directly involved. Other citizen-centred services, such as education, communication, outreach and participation services, play a key role.

However, links between these services and the staff responsible for petitions are not always well established. Petitions to parliament are considered to be parliamentary business, but they are also led by citizens. Supporting the petitions process therefore requires closer collaboration between those services that focus on enhancing the public’s understanding of parliament.

The need to be proactive

Overall, we found people have considerable interest in political issues and petitions, including those within seldom-heard groups. However, there is also deep mistrust within these groups, often coupled with a lack of knowledge, skills and confidence to engage with participatory tools such as petitions.

To expand the reach of petitions beyond the usual suspects, parliaments need to be proactive in reaching out to a wider audience. The mere fact a participatory tool exists does not mean it will be used by everyone. Our research underlines the importance of education and clear communication for enhancing the value of participatory tools.

This article is based on research undertaken by Cristina Leston-Bandeira and Blagovesta Tacheva and funded by Research England. The research was presented at the PSA Parliaments Annual Conference, hosted by the LSE School of Government on 3 November 2023.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: UK Government and Parliament Petition platform as of January 30 2024. Credit: UK Parliament 2024.