The format of UK election debates has been highly unstable since the first broadcast occurred in the 2010 General Election. Ahead of an upcoming general election, Nick Anstead writes that the absence of a governing body or even clearly understood guidance to regulate such debates does a disservice to their democratic potential, creating a system that is rushed and haphazard.

That a UK general election will be called this year reopens what has now become a recurring discussion about televised election debates. Broadly, the conversation tends to boil down to two questions. First, are they going to happen at all? And second, if they do happen, what format should they take, and who will be invited to appear on them?

The heavy focus on election debates during campaign period is perhaps ironic, given that the academic evidence for them actually changing election results is limited to non-existent. But we do know that debates are central to many voters’ election experience, and that decisions taken about their format can embed a variety of democratic attributes.

The UK’s short history of TV election debates

In this context, it is worth noting two things about the history of televised election debates in the UK. First, it took the UK a long time to hold its first debate in 2010. This was a half century after the world’s most famous early television debate, Kennedy vs Nixon in the 1960 US Presidential elections. An obvious explanation for the UK’s failure to hold debates for such a long time is the system of Parliamentary democracy, where a general election is made up of 650 individual contests, each with their own candidates, dynamics and plausible winners.

In every election until 2010 where debates were suggested, there was always one candidate from either the Conservatives or Labour Parties who vetoed proposals for a broadcast.

However, this obvious explanation is also wrong. As I detailed in my 2016 article on the subject, plenty of Parliamentary democracies (including Canada, West Germany/Germany and Australia) managed to hold election debates decades before the UK. The real explanation for the UK’s late adoption of debates seems to have much more to do with the self-interested calculations of politicians. In every election until 2010 where debates were suggested, there was always one candidate from either the Conservatives or Labour Parties who vetoed proposals for a broadcast.

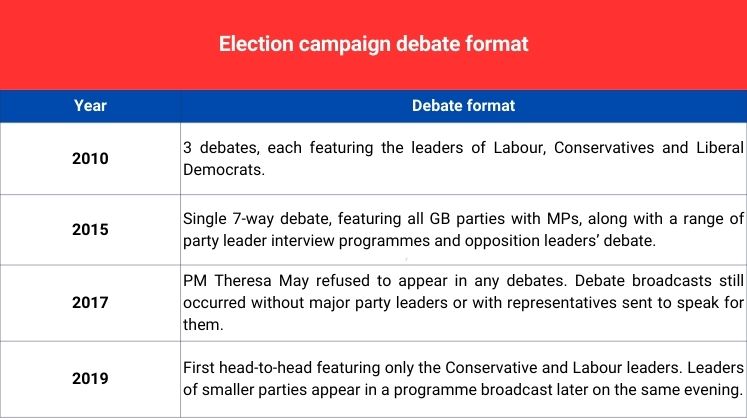

The second observation about the history of UK TV debates is the instability of the format since 2010. Every general election in this period (four in total) has featured different types of debates — no format has ever been repeated.

The debate format has changed so much for several reasons. No attempt has ever been made to clearly define fixed criteria for inclusion in the debates, which is different to other countries where various formal and semiformal inclusion rules operate — for example, having a seat in the legislature or regularly polling over five per cent. Instead, the UK’s format is renegotiated each election. Furthermore, the arrangement used in the 2010 negotiations, when the three major broadcasters (BBC, ITV and Sky) acted as a consortium and negotiated together, has now largely broken down, with each broadcaster making their own offers. This means politicians can pick and choose the proposal that most closely aligns with their interests.

The relevance of changing political attitudes

There are also structural causes of instability in the debate format. This reflects a major change in how British citizens (and indeed citizens in various liberal democracies in the West) relate to the political system — specifically, a declining propensity to strongly identify with a particular political party and, as a result, continuously support them over multiple election cycles. This is what political scientists refer to as dealignment.

In the context of TV debates, dealignment has had contradictory effects. It has degraded the traditional party system as more voters are willing to consider alternatives to the Conservatives, Labour, and even the Liberal Democrats. Scotland and Wales now have large nationalist parties, the Greens have had an MP for over a decade, and UKIP has had a massive influence over the course of British politics. It was these dynamics which framed the 7-way debate format chosen in 2015.

At the same time, though, declining long-term affiliation with political parties has made elections more leader-centric, with an increased proportion of the electorate basing their vote on party leader preferences. In such an environment, it makes sense for debates to focus on the leaders who are most likely to win executive authority, a logic embedded in the 2019 Johnson vs Corbyn debates.

Is one of these formats better than another? It is a question of trade-offs. Instinctively, many of us might favour pluralism, and seek to include a range of large and small parties (certainly something I argued for in interventions I wrote before the 2015 election). Retrospectively, though, I think I missed some drawbacks of this approach. As viewers of the 2015 debate will remember, it was quite a confused spectacle. More voices on stage made it harder to have in-depth, focused conversations. Genuine democratic goods, such as increased public knowledge or the chance to hold politicians accountable, might therefore be undermined.

A way forward

The problem is that debate negotiations tend to be rushed, often taking place in the months or even weeks before an election, so there is no real time to consider these sort of trade offs. Instead, they are driven — as they have always been — by the self-interest of political and media actors. It is therefore worth asking how debates can be better organised.

Canada, a comparable Westminster-style parliamentary democracy, offers one possibility. In the run-up to the 2019 election, the country established an independent debate commission (a distinct model from the American Commission on Presidential Debates, which is technically a bi-partisan organisation). Significantly, the Canadian Commission has not only been charged with organising election debates but also produces post-debate reports and research, making recommendations for future election cycles. It is this kind of reflection across elections that the UK has so clearly lacked in its short but eventful debate history. It is probably too late to instigate such a system for the likely 2024 general election, but we can at least hope it is the last British election where debate organisation occurs in such a haphazard manner.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image: A viewer watches election live TV debate on a computer monitor on Apr 4, 2015 in London, UK. Credit: 1000 Words on Shutterstock.