In the UK’s first past the post system, the main battle will always be between the two major parties. But which party takes third place is also crucial. Even if not the official opposition, third parties have rights that afford them public funding, air-time during Prime Minister’s Question Time and guaranteed representation on key commons committees. If the SNP lose their third party rights, that will affect bot just the party but the balance of power in the House of Commons.

The UK’s majoritarian electoral system means that general election battles are always going to be dominated by the two largest political parties, the Conservatives and Labour. But last week’s multi-party leadership debate held by the BBC gave voters a chance to hear from seven different political parties. The sheer number of podiums made it difficult to even get a full shot of all of the party representatives and the 90 minute slot meant that each question from the audience brought only a short response from the parties, with no real opportunity for any follow ups. Viewers may have left knowing very little about each party’s stance on the big issues, but the debate told us two very clear things about this election campaign.

Firstly, it re-emphasised two-party majoritarian politics, something which was reinforced immediately by the party’s positions on the podiums. Labour’s Angela Rayner and the Conservatives’ Penny Morduant continually battled against each other, dominating the conversation on taxes and on the Trident nuclear deterrent, effectively locking the smaller parties out of chunks of the debate. Their purpose was clearly to try and articulate their policy differences and to differentiate themselves from the other. Small party policies were tangential to their discussions. The smaller parties themselves seemed quite ready to acknowledge this two-party dominance, with the Green, SNP, Plaid Cymru and Reform representatives making it clear that they were expecting a Labour victory. The polls corroborate this, predicting a record win for Keir Starmer.

All of the small parties worked hard to distance themselves from the larger two.

It may have felt quite futile for the five smaller parties in places, but this was perhaps because they were there to fight a different battle. Although smaller parties may be facing Conservative or Labour candidates in some neck and neck constituency level campaigns, they are not fighting them to be in government. After all, their leaders are never going to be Prime Minister. The SNP and Plaid Cymru speak to a clearly defined, nationally focused Scottish and Welsh electorate, while the Greens readily admit that they will not be walking into Downing Street after the election and have the modest target of 4 MPs and their largest share of the national vote to date. All of the small parties worked hard to distance themselves from the larger two. Green Party co-leader Carla Denyer and Reform UK’s Nigel Farage both chose to use their closing speeches to stress the lack of any real policy differences between the Conservatives and Labour.

Parties who are not in government want to influence the political debate. They want to hold government to account and to try to force policy change. But they need party rights to be able to do this.

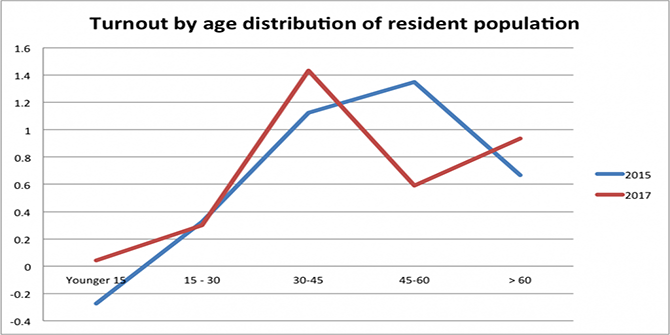

The battle for these parties is for their position in the opposition hierarchy. Although it’s unlikely that the Conservative party vote will fall low enough for them not to be the largest opposition party, there is still a potentially very interesting battle for third party status. This has been held by the SNP since the 2015 general election, but with Labour seemingly set to retake some key SNP seats, they may not hold it any longer. Parties who are not in government want to influence the political debate. They want to hold government to account and to try to force policy change. But they need party rights to be able to do this. And third-party rights, although not as generous as those given to the Official Opposition, bring the opportunity to do this. They enable guaranteed air-time on the floor of the House of Commons chamber at Prime Minister’s Question Time and they ensure some guaranteed representation on key commons committees. This is critical for parties who want to get their views heard. The SNP’s Westminster Leader Stephen Flynn for example has regularly pressed Rishi Sunak on everything from conservative party donors to graduate work visas. Smaller parties may wait several weeks to get a PMQs question. Flynn receives two every week.

If the SNP lose a large number of seats as predicted next month, they will also lose a considerable amount of public funding.

Short Money funding, which helps opposition parties to recruit staff and maintain party offices at Westminster, is another key component. This is public funding provided to opposition parties to enable them to carry out their parliamentary duties. It is allocated to parties, not to individual MPs and enables for instance, the funding of an office for the Leader of the Opposition. A complex formula is used to calculate how much funding each party receives, which includes both the number of MPs returned and the number of votes received. It means that parties are rewarded if they perform well, but will face financial losses if they perform poorly. Therefore, if the SNP lose a large number of seats as predicted next month, they will also lose a considerable amount of this public funding, which amounted to £1.3million in 2023-24.

This money has previously helped to pay the salaries of 18 members of party staff at Westminster. The Greens know full well how costly under-performing in this way can be. Their fall in votes in the 2017 general election cost them a great deal in Short Money and forced them to launch a crowdfunding campaign to ensure they could retain party staff to help them “skewer ministers” in the Commons chamber. Reform UK would only need to return one MP to be in receipt of this funding and they could potentially do very well out of it, even if they haven’t met their aim of fielding a candidate in every English constituency. We saw this happen with UKIP’s Douglas Carswell back in 2015. The Liberal Democrats are also likely to do well in the short money stakes, picking up additional votes through tactical voting in constituencies where they currently lie in second place behind the Conservatives. So although the First Past The Post electoral system works against smaller parties, particularly those like the Greens whose support is less concentrated in constituencies, when it comes to building a strong parliamentary opposition party, every vote really does count.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Iscotlanda Photography on Shutterstock