The distribution of wealth and how it should be addressed in policy is a largely absent topic in the debate about reducing poverty. Anna Rosso argues that the objective should not just be to redistribute wealth through the tax and benefit system, but how to put in place the right incentives to create a savings culture.

The distribution of wealth and how it should be addressed in policy is a largely absent topic in the debate about reducing poverty. Anna Rosso argues that the objective should not just be to redistribute wealth through the tax and benefit system, but how to put in place the right incentives to create a savings culture.

Two nations; between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts, and feelings, as if they were dwellers in different zones, or inhabitants of different planets; who are formed by a different breeding, are fed by a different food, are ordered by different manners, and are not governed by the same laws: the rich and the poor. [Benjamin Disraeli, Conservative Prime Minister and author, Sybil, 1845]

Peter Mandelson famously said that he was “intensely relaxed” about people becoming “filthy rich”, so long as they paid their taxes. The Labour government’s anti-poverty strategy during the 2000s essentially ignored wealth inequality. However, with wealth distributed even more unequally than income, can a long-term anti-poverty strategy ignore wealth?

The distribution of wealth (as opposed to income), and how it should be addressed is a largely absent topic in the economic debate about poverty. Yet, studies show that having assets matters. Research that tries to disentangle the wealth effect from other factors that affect people’s life chances shows that wealth does matter – even over and above life factors that affect chances (such as parental income) there is still a wealth effect. It does matter whether you grew up in a family that has assets: the children of such families are likely to do better in health, education and economic opportunities and wellbeing. The same is true for young adults, they do better than others with comparable incomes and education. And since the distribution of wealth is far more unequal than income, this is likely to have significant impact in exacerbating inequality and reducing social mobility. Moreover, these inequalities hold through the life cycle.

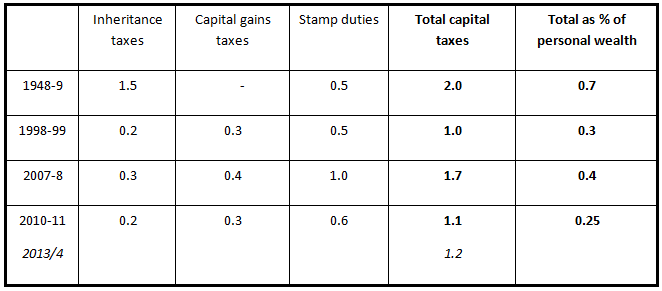

Yet, relatively little – and considerably less than in the past – is done to directly redress wealth inequalities. As the table shows, taxes on capital and land have fallen substantially (in relation to GDP or to overall revenues) over the last century.

Table 1: Tax revenue as a percentage of GDP

Moreover, the last government’s tentative efforts to support wealth accumulation by the poor (the Child Trust Fund and Savings Gateway) were abolished by the current administration. In a period of fiscal stress there are good arguments to try to reverse this trend, even leaving aside equity and poverty issues. The objective should not (just) be to redistribute wealth through the tax and benefit system but to put in place to create the right incentives for people to start saving and investing money in order to create a saving culture.

So what are the main policy options?

- Taxation on land and property. Almost all economists would agree, first, that taxes on residential property/land are “good” taxes (they are unlikely to distort decisions or discourage business or enterprise much; property can’t be moved abroad to avoid them; and, in the UK, much of the wealth in land or property simply reflects windfall gains to relatively richer and older people); and second, that the current system is both inefficient (stamp duty) and regressive (council tax). So the scope for a more economically efficient system, based on a progressive land or property tax, is considerable. However, attempts to move in this direction have frequently encountered political difficulties.

- Pensions and saving. As with land, the system of taxes and tax reliefs on pensions is both regressive (as most of the benefit goes to higher earners) and excessively complex. More than 50% of the total costs of pension tax reliefs are received by top earners, while only 8% is received by individuals at the bottom. Restricting pension tax reliefs for top incomes and giving more “flat-rate” reliefs would both simplify the system and redistribute wealth.

- Long term care. The “solution” set out in the Dilnot report essentially represents a further state subsidy to relatively well-off property owners. Some form of deferred payment scheme, and/or greater use of equity release products to allow property-rich (but possibly income poor) elderly to pay the costs of their own care could help here.

- At the other end of the income scale, simple and accessible schemes that incentivised relatively poor people to build up long-term assets – like the savings gateway or similar – nudge people into the idea of savings, might both help people build up asset pools for the future, and avoid the trap of large and bad debts.

Experience shows that taxing wealth and property more in the UK raises huge political difficulties – but it does offer the rare opportunity to combine economic efficiency with policies that could ease the general fiscal squeeze and help to address poverty both in the short and the long term. Disraeli would be wondering what we were waiting for.

This blog is NIESR’s write-up of a seminar that took place on 12 November as part of an ongoing series on the subject of “Money and Poverty”. The series is part of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s ongoing programme devoted to the creation of strategies to eliminate poverty in the UK over the next 20 years. The idea of the programme is to find alternative solutions which could be a combination of different approaches in order to raise the capabilities and opportunities for people in poor conditions to access the resources they need for subsistence. This seminar was opened by Howard Glennerster, with a brief presentation based on his book and was attended by a number of experts in the field. The views above are entirely the responsibility of NIESR, not of Professor Glennerster, JRF, or the seminar participants.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Anna Rosso joined NIESR as a Research Fellow in 2012. She previously worked as a research assistant for the Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM) based at UCL where she is about to complete the PhD in Economics.

Anna Rosso joined NIESR as a Research Fellow in 2012. She previously worked as a research assistant for the Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM) based at UCL where she is about to complete the PhD in Economics.

1 Comments