Jens Wäckerle shows how Labour has fared better than the Conservatives in increasing its share of women MPs by nominating women in winnable situations through All-Women Shortlists. He also shows how a party running women in an election leads to more women being nominated in neighbouring constituencies in subsequent elections.

Jens Wäckerle shows how Labour has fared better than the Conservatives in increasing its share of women MPs by nominating women in winnable situations through All-Women Shortlists. He also shows how a party running women in an election leads to more women being nominated in neighbouring constituencies in subsequent elections.

We will change the way we look. Nine out of 10 Conservative MPs, like me, are white men. We need to change the scandalous under representation of women in the Conservative party and we’ll do that. (David Cameron, Leadership acceptance speech, 2005)

We will reform the House of Commons […] to achieve through our party the increase in the number of women MPs that we have talked about for so long. (Tony Blair, Leader’s speech, 1994)

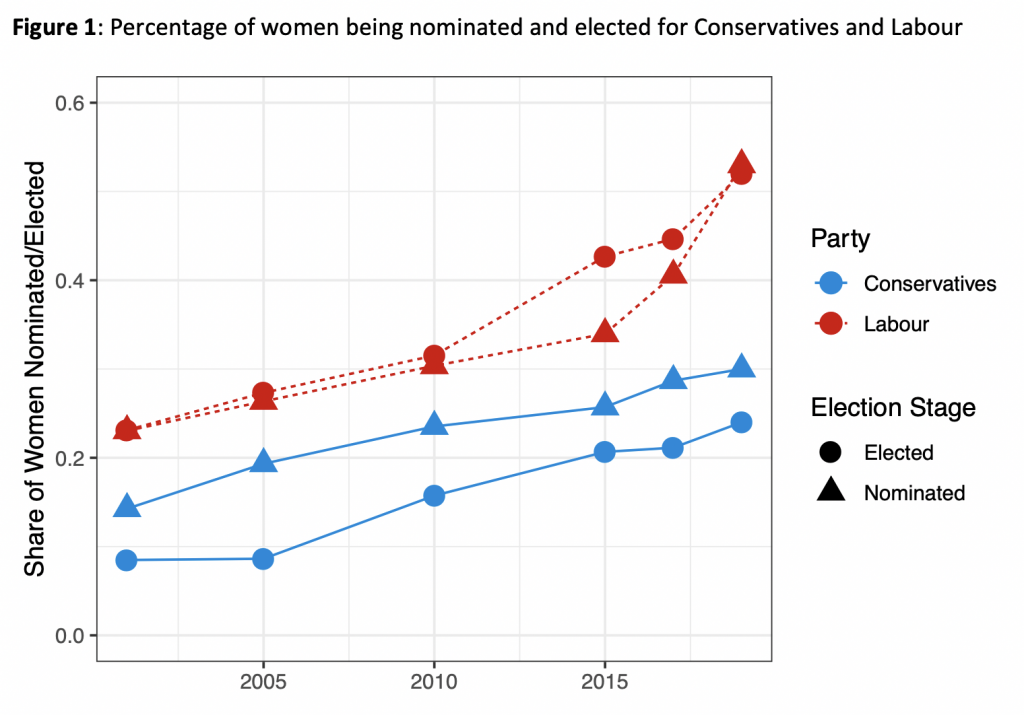

Despite similar aspirations, Labour has increased the share of women MPs above 50% in the past 20 years, while the Conservatives have fallen way short of that mark. Figure 1 shows that trend over time and also reveals a second development: women in the Labour Party make up a larger share of MPs than candidates, while the opposite is true for the Conservatives.

Why is that? In a recent article, I found that there are two main forces at play: Labour nominates women in far more electorally promising situations than men, and when one constituency nominates women, it leads to neighbouring constituencies also being more likely to do so.

For a while now, there has been discussion of the ‘glass cliff’ of women’s representation. The term is related to the more common term ‘glass ceiling’, which describes the fact that women of reach a certain level in organizations, but then fail to progress higher (for example women might become local council members, but not MPs, or regional head of production, but not CEO). The glass ceiling, meanwhile, describes the situation that women are often promoted and put in leadership positions when times are bad, for example when a company is failing, cases in court are likely to be lost, and parties are fairly sure they will lose an election. The latter leads to women being nominated in places where they have very little chance of winning. In other words, a party might increase the number of women candidates, but mostly in constituencies they are all but certain to lose.

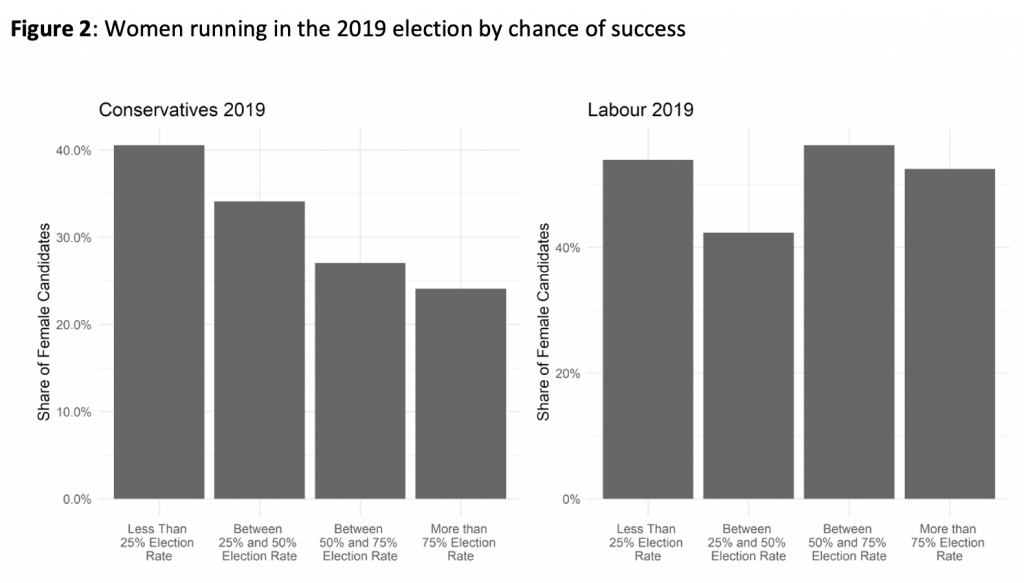

We can see such a glass cliff for the Conservatives, as Figure 2 shows: in constituencies that the Conservatives were less than 25% likely to win, more than 40% of candidates were women. Meanwhile, in constituencies that the Conservatives were more than 75% sure to win, only 25% of candidates were women. Efforts of the Conservatives to increase the share of women among candidates, such as the A-List or Theresa May’s ‘Women2Win’ campaign did help to increase the number of women among candidates somewhat, but many of them were nominated in very bleak situations.

Meanwhile, Labour nominated women fairly evenly across constituencies: places that they were likely to win had about as many women running as those they were likely to lose. Since the early 1990s, Labour has been using All-Women Shortlists to nominate women in particularly promising situations. While hotly discussed among party supporters, the media and the public (and briefly banned due to a court challenge in 2001), they had one very clear effect: many more women were nominated, and they were nominated in places they could win. Consequently, this targeted, top-down measure was highly effective in addressing women’s underrepresentation in politics: The share of Labour MPs that are women rose from 25% to 50% in less than 20 years.

One way in which women’s representation spreads across parties, countries, and regions is the phenomenon of contagion. Once one party nominates a woman in a certain constituency, other parties and/or neighbouring constituencies might be more likely to do so as well. Reasons for this may be positive newspaper coverage, pressure from women’s associations within a party, or the fear of losing women voters. On the national level, parties often observe other parties increasing women’s representation and feel compelled to do so as well. Especially, parties on the left prioritise women’s representation once competitors from the left challenge them on the issue. In the UK, the Liberal Democrats too use a version of All-Women Shortlists. While discussions on the use of the latter have been going on in the Conservative party, the leadership has refrained from taking such strong measures.

Geographically, I find that one constituency nominating a woman will lead to other constituencies being more likely to do so as well in the subsequent election, if they are reasonably close. This means that a party can increase women’s representation in a certain region by having only some of the constituencies nominating women, which then also increases the likelihood of others doing the same.

Across the political spectrum in many countries, party leadership is working to increase the number of women among MPs. However, parties in single-member district systems often have a hard time doing so: if a party nominates only a single candidate per constituency, quotas are difficult to construct and local parties have historically often nominated men to run in such contests. The example of the Labour Party shows how a combination of reserving certain electorally promising seats for women and subsequently neighbouring constituencies being likelier to nominate women, led to the party doubling the share of women among their MPs in 20 years. Meanwhile, the example of the Conservatives shows that soft measures such as recruitment efforts and public relations campaigns will only get you so far – there might be some additional women candidates, but they are also likely to run in constituencies they have little chance of winning. These measures are simply not enough to increase the share of women among MPs by a considerable margin.

____________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in Party Politics.

Jens Wäckerle is a doctoral researcher at the Cologne Center for Comparative Politics at the University of Cologne.

Jens Wäckerle is a doctoral researcher at the Cologne Center for Comparative Politics at the University of Cologne.