Despite the existence of the NHS, the UK has a Gender Health Gap. Women, especially those of low socio-economic status, have worse health outcomes than men. Genevieve Jeffrey traces the history of this health discrepancy from pre-NHS times to the present, focussing on the inequities of maternity care.

As women live longer than men, it’s disheartening to discover that they spend 25 per cent more of their lives in debilitating health compared to their male counterparts. This “Gender Health Gap” encompasses a disparity in health access, funding, and prioritization based on gender. Compared to men, women visit the GP less, are more likely to consume medication that could be harmful, in the case of dementia receive poorer medical treatment, and are twice as likely to die in the immediate 30 days after experiencing a heart attack.

In the present-day context, efforts are underway to rectify these disparities, with the Women’s Health Strategy 2024 representing a significant step forward. This includes initiatives like increased research funding on maternal disparities, the establishment of specialist women’s health hubs in local health areas, and a dedicated section on women’s health on the NHS website. But the Gender Health Gap has deep historical roots and will be hard to undo. The historical landscape of women’s healthcare access in the UK paints a stark picture of inequity. There are lessons to be learned from the history of this expression of gender inequality that can help guide today’s policymakers.

Across various healthcare scenarios, women’s health outcomes were significantly influenced by socioeconomic status, underscoring its role as a critical determinant of access to healthcare.

Before the establishment of the National Health Service (NHS), women’s access to healthcare was largely contingent upon financial means. The 1911 National Insurance Act aimed to broaden access by introducing an insurance component, yet benefits primarily applied to employed individuals, leaving married women who tended to be housewives and not engage in employment without entitlements. Despite later expansions in 1946, only 40 per cent of the population was covered, prompting many women to delay seeking the consult of a medical professional to avoid the out-of-pocket expense, preferring instead to visit the chemist, and rely on home remedies, until the symptoms progressed to be serious. This meant women suffering from avoidable illnesses and the progression of illnesses that could have been addressed at an earlier stage.

Essentially, prior to the establishment of the NHS, any medical care recommended by doctors incurred out-of-pocket expenses for the mother, including consultations. For instance, if a woman was prescribed calcium pills but couldn’t afford them, her treatment would have been interrupted. Conversely, after the advent of the NHS, treatment prescribed by a GP would have been provided free of charge, enabling her to complete her course of treatment. Across various healthcare scenarios, women’s health outcomes were significantly influenced by socioeconomic status, underscoring its role as a critical determinant of access to healthcare.

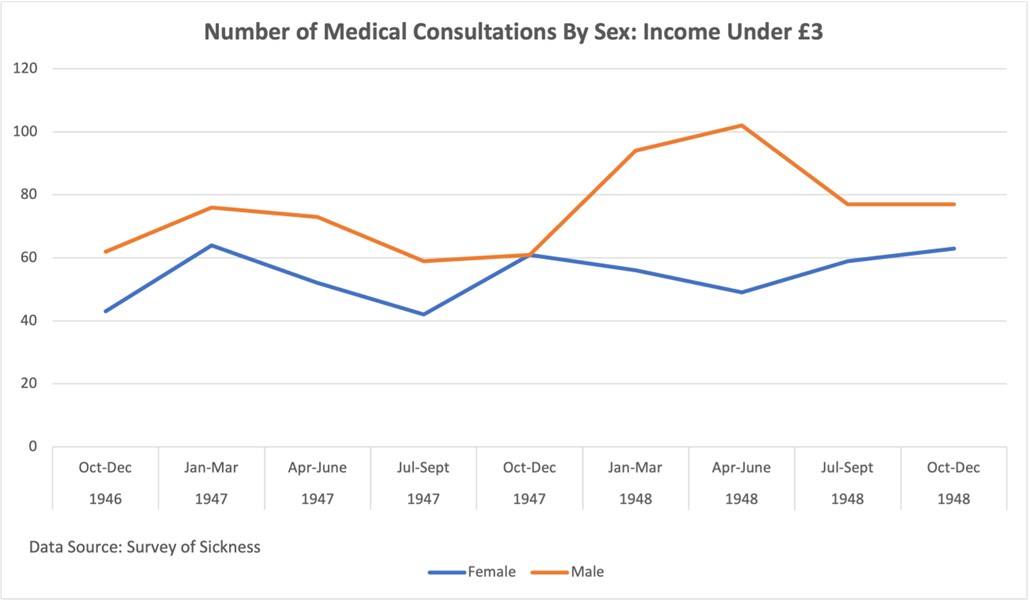

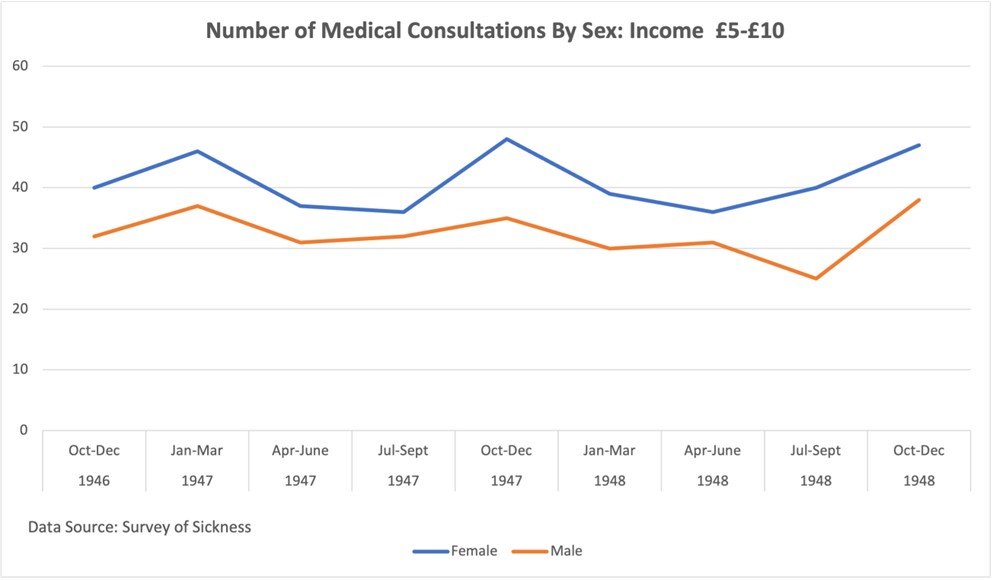

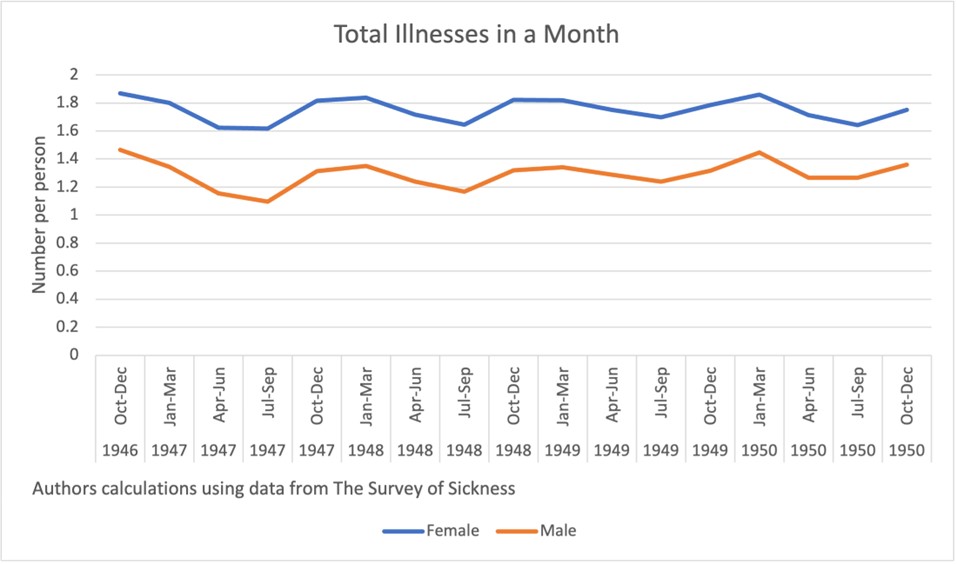

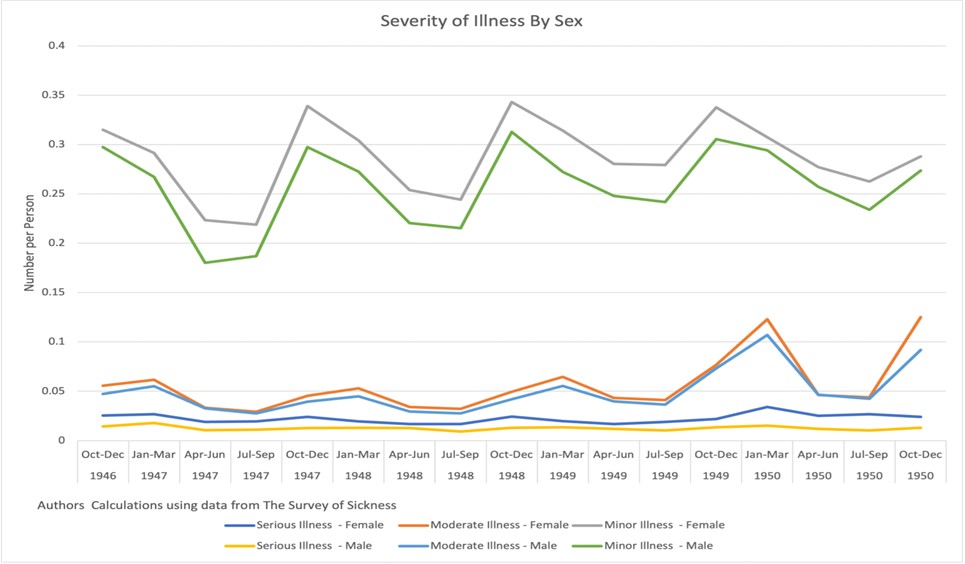

The figures above clearly show that in the period between 1946 and 1950, in the lower socioeconomic groups, the men had a higher number of medical consultations than women. For higher incomes, women had a higher number of medical consultations. Women also reported a larger number of illnesses than men.

What the figures below indicate is that while the healthcare needs were higher for women, there was an underuse of healthcare services in the lower socioeconomic groups due to an inability to afford the medical consultations.

One aspect unique to women’s interaction with the healthcare system is their experience with maternity services. Before the NHS era, maternity services were structured to address three key periods: during pregnancy, at birth, and after childbirth. During pregnancy, services focused on educating mothers through health visitors and infant welfare centres. Local governments provided medical supervision through trained midwives and nurses, along with hospital care for pregnancy complications and support such as milk and food supplements and maternity homes for mild ailments. During childbirth, doctors assisted midwives in emergencies, and postpartum care included hospital accommodation, convalescent homes, and home assistance. However, the scope and quality of these services varied significantly among local government bodies, leading to differing barriers to access and disparities in costs and availability.

The Gender Health Gap remains a poignant reflection of systemic disparities in healthcare access and outcomes, disproportionately affecting women’s well-being despite their longer life expectancy.

In a survey of all married women who delivered in one week in March 1946, mothers were classified by the occupational group of their husbands and it was found that mothers from the higher socioeconomic groups accessed their first antenatal appointment in the twenty-first week (2nd Trimester) while mothers from the lower socioeconomic status groups waited, on average until the thirty-third week (3rd Trimester). Going forward to 2010, the National Maternity Survey found similar trends, where compared to the least deprived women, the most deprived group were likely to be able to access a healthcare professional as early into the pregnancy as they wanted. Compared to women in the least deprived areas, those in the most deprived areas were more than twice as likely to experience a maternity related death.

Despite the introduction of the NHS, which aimed to provide universal healthcare coverage, these disparities in maternity healthcare access persist. While the NHS has undoubtedly improved access to healthcare for many, including maternity services, the underlying socio-economic factors continue to play a significant role in determining the quality and timeliness of care received by pregnant women. Moreover, the challenges identified in the 1946 survey regarding access to prenatal care and healthcare professionals early in pregnancy remain relevant today. Therefore, addressing these persistent disparities requires ongoing efforts to tackle the root causes of inequality, including socio-economic disparities, and to ensure that maternity services are accessible and of high quality for all women, regardless of their background or circumstances.

The Gender Health Gap remains a poignant reflection of systemic disparities in healthcare access and outcomes, disproportionately affecting women’s well-being despite their longer life expectancy. Efforts such as the Women’s Health Strategy 2024 signal a commitment to address these disparities, yet historical inequities in healthcare access persist, particularly evident in the pre-NHS era where financial means dictated access to care. While strides have been made in improving maternity services, socio-economic status continues to shape women’s health outcomes, highlighting the need for sustained efforts to mitigate disparities.

The figures presented underscore the intersectionality of gender and socio-economic status in healthcare access, emphasizing the ongoing challenge of ensuring equitable healthcare for all individuals. Addressing these entrenched disparities requires a multifaceted approach that prioritizes accessibility, affordability, and quality of care. Only then can we ensure that women receive the support and resources necessary to achieve optimal health outcomes across their lifespan.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: chrisdorney on Shutterstock