Would the Conservative party benefit from Scottish independence? In this post, Jack Blumenau and Ben Lauderdale use estimates from a new statistical model to investigate election outcomes under different referendum scenarios. They show that holding current polling fixed, the probability of a Conservative majority at the next election is 52 per cent excluding Scottish seats, versus 21 per cent including them. They then calculate how many voters would have to “punish” the Conservatives for “losing Scotland” in order to counter-act this shift of the political center towards the Conservatives. Contrary to popular belief, they find that a relatively small swing from the Conservatives to Labour is sufficient for Labour to recover from losing its Scottish MPs.

Would the Conservative party benefit from Scottish independence? In this post, Jack Blumenau and Ben Lauderdale use estimates from a new statistical model to investigate election outcomes under different referendum scenarios. They show that holding current polling fixed, the probability of a Conservative majority at the next election is 52 per cent excluding Scottish seats, versus 21 per cent including them. They then calculate how many voters would have to “punish” the Conservatives for “losing Scotland” in order to counter-act this shift of the political center towards the Conservatives. Contrary to popular belief, they find that a relatively small swing from the Conservatives to Labour is sufficient for Labour to recover from losing its Scottish MPs.

Would the Conservative party benefit from Scottish independence? Would Labour never form a majority government again? As the referendum draws closer, and the polls tighten between the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ camps, a common refrain is that by depriving Labour of its Scottish MPs, a Yes vote would seriously impair its ability to garner a majority in Parliament, and make the formation of Conservative majorities easier. Accordingly, so the argument goes, there will be more single-party Conservative governments in Westminster if the people of Scotland vote for independence on September 18th. The belief that Labour will face electoral Armageddon without Scottish support is widespread, and fiercely espoused. For George Galloway, Scottish independence “will lead to permanent Tory rule in Westminster.” For Sean Thomas, of the Telegraph, “without Scotland, Labour will be mutilated and traumatised for a generation.”

However, most empirical analyses of this question have relied solely on historical comparisons (for example, here, here and here), which suggest that the independence of Scotland would have significantly affected the Parliamentary arithmetic of previous elections. For example, had Scotland been independent at the time of the last election, the Conservatives would have secured an outright majority in 2010. Conversely, the Labour majority of October 1974 would have been reduced to a plurality without the inclusion of Scottish MPs. The removal of Scottish MPs from Westminster in 1964 would have had an even bigger effect: Labour would have lost its majority, and been replaced by the Conservatives as the plurality party. The historical record therefore seems to support the contention that the Conservatives would benefit from a ‘Yes’ vote, as, without the Scottish contingent, they would hold (proportionally) more seats in Parliament.

However, the more relevant question is how much Scottish independence would affect elections in the future. In this post, we ask: what will the division of seats look like after the 2015 general election in the hypothetical rUK (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) versus the current UK? We use estimates from a recently developed statistical model (full details of which can be found here and here) to see what a post-independence Westminster government might look like. The model incorporates historical, geographic, demographic and polling data to predict vote shares of all major parties, in each constituency. These seat-level forecasts allow us to make probabilistic statements about the overall distribution of seats for each party, and we can use this to predict outcomes for both the UK as it currently exists, and the UK excluding the 59 seats in Scotland.

First, we construct our predictions by simply excluding the 59 Scottish seats from our current UK-wide forecast, and in so doing, we implicitly assume that there will be no overall change in voters’ evaluation of the parties in response to a ‘Yes’ vote. Then, we will explore how the results change if voters in England and Wales change their voting intentions in response to a ‘Yes’ vote.

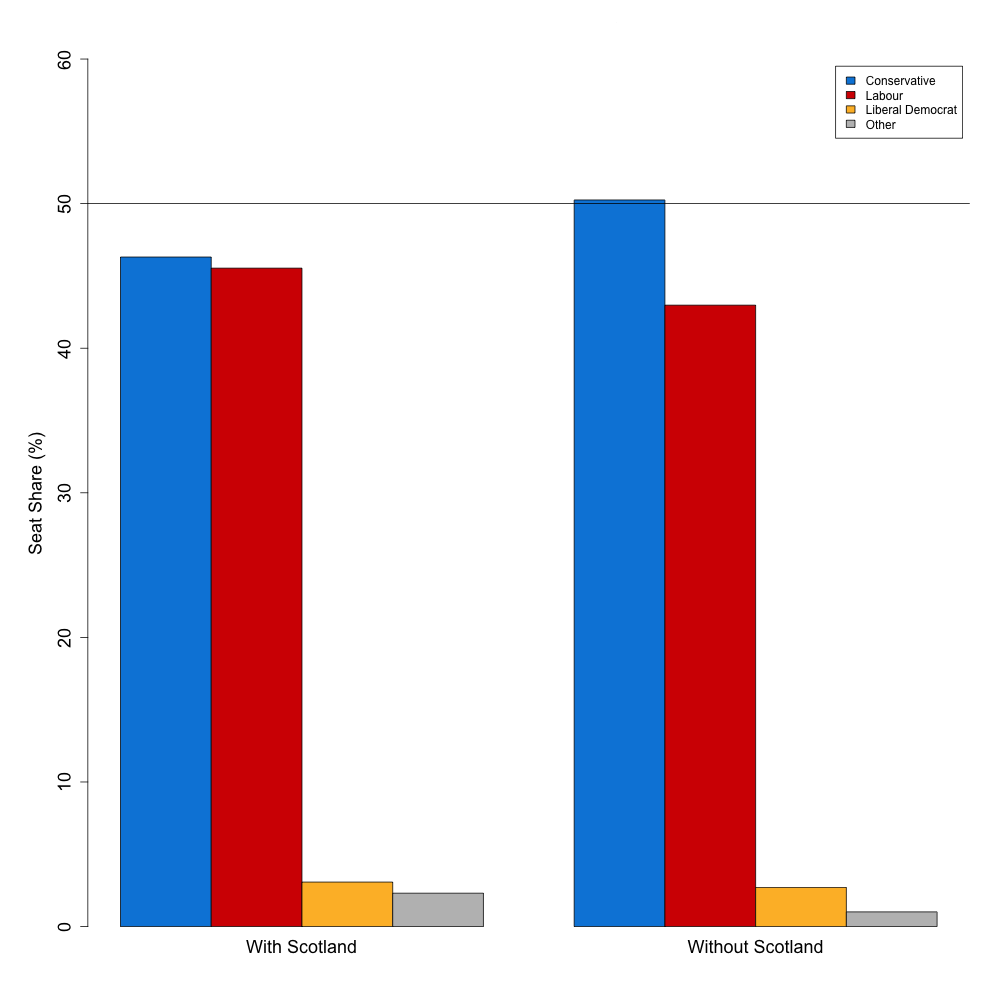

Figure 1: Predicted seat share in 2015 (click on image to enlarge)

Figure 1 shows the main comparison of interest: the seats predicted for each party including Scotland (under a No vote), and excluding Scotland (a Yes vote). Our best guess currently is that the Conservative party will fall short of a majority, securing only a narrow plurality. However, if Scottish seats are excluded, among the remaining seats the Conservatives have a narrow majority. When including Scottish MPs, the Conservatives are predicted to hold 46.3 per cent of seats in Westminster, with Labour slightly behind with 45.5 per cent of the seats. Excluding Scottish MPs increases the Conservative share of the seats to 50.25 per cent and reduces Labour to 42.9 per cent, enabling the formation of a very narrow Conservative majority government.

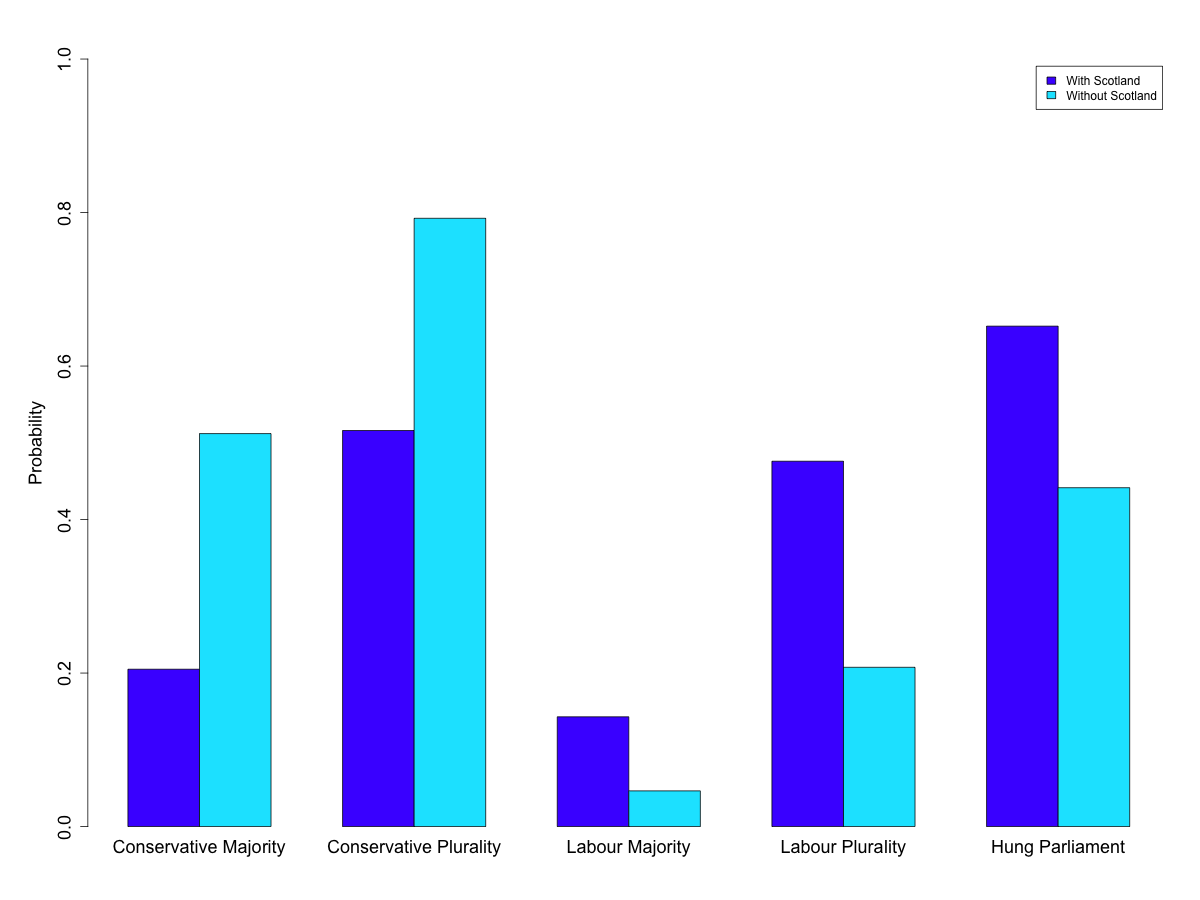

However, eight months from the general election, these forecasts have a great deal of uncertainty associated with them. More usefully, we can instead provide probabilistic statements about various outcomes of interest. In the context of the next election, there are two key questions: 1) Will either the Conservatives or Labour hold enough seats to win a majority? 2) If not, which party will hold the greatest number of seats? Figure two illustrates the probabilities of these outcomes, as well as the probability of a hung parliament. The dark blue bars represent these probabilities including Scotland, and the light blue bars excluding Scotland.

Figure 2: Probability of different scenarios in 2015 (click on image to enlarge)

The message is clear: when Scottish MPs are excluded, a Conservative plurality or majority is more likely, and a Labour plurality or majority is less likely. Specifically, the probability of a Conservative majority increases from 21 per cent to 52 per cent, and the probability that the Conservatives will hold the most seats increases from 52 per cent to 79 per cent.

While we (unsurprisingly) predict that Labour would suffer in the event of a ‘Yes’ vote, these shifts are not so large as to constitute inevitable exclusion of Labour from power. The probability of a Labour majority decreases from 14 per cent to 5 per cent, and the probability a Labour plurality drops from 48 per cent to 21 per cent. While these are both substantial decreases, they certainly do not imply that Labour’s political situation is immediately and forever hopeless.

Most fundamentally, as we have noted above, all of this assumes that no one in the rUK changes their vote intention in spite of what would clearly be a singular political event. Some have argued that the Conservatives might be punished by voters for presiding over the debacle of “losing Scotland”. How much would they need to be punished in order to counter-act the effect of excluding Scottish seats, at least for the upcoming general election?

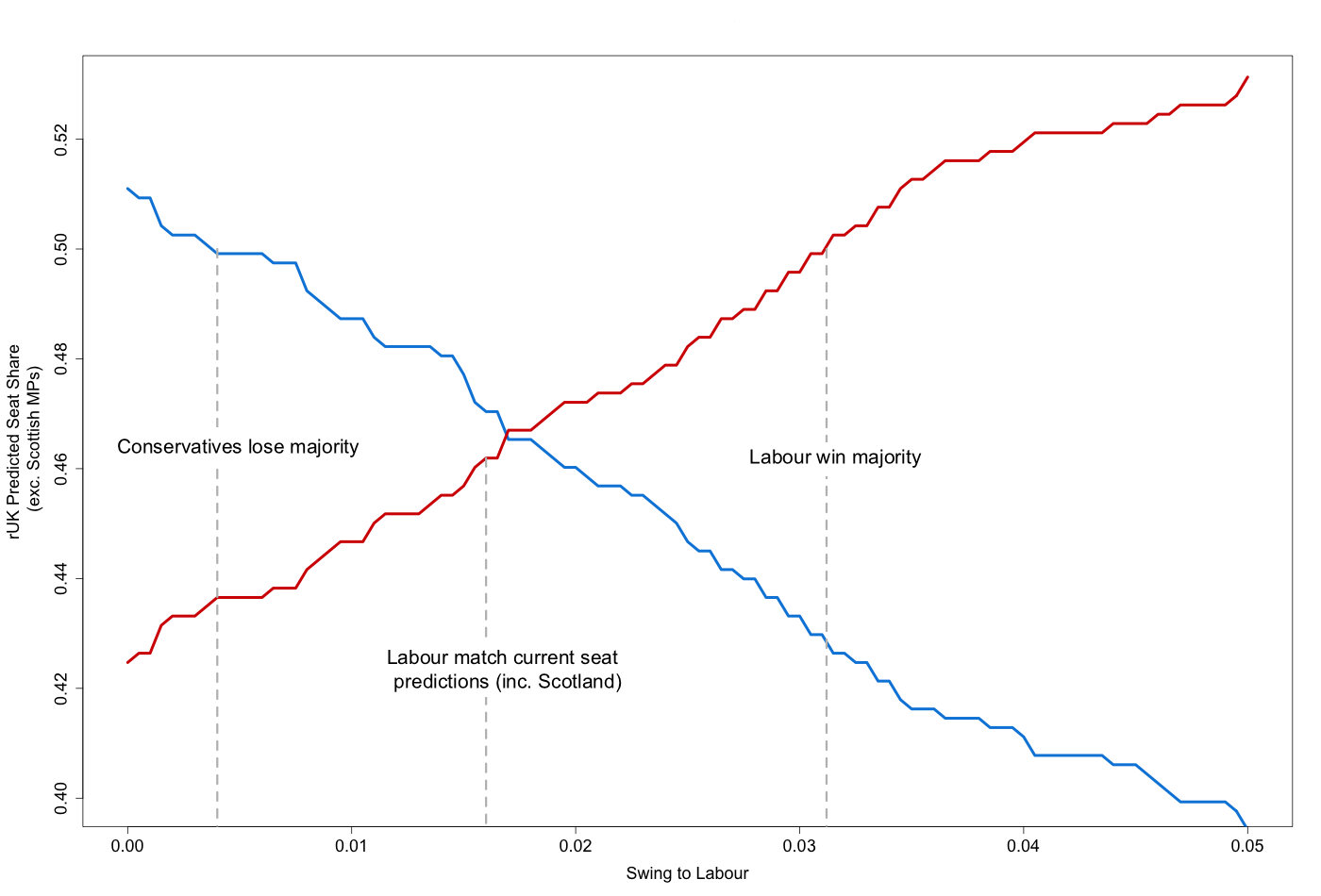

The forecasting model that we are using includes a close variant on the commonly used Uniform National Swing, and we can ask how large a shift among English and Welsh voters from the Conservatives towards Labour would return Labour’s forecasted seat share to the values we calculate currently including Scotland. Here, we set aside the Liberal Democrats and UKIP for simplicity, as it is shifts between Labour and the Conservatives that have the largest effect on seat share between those parties.

Figure 3 shows what shifts are needed relative to the current forecasted voting share for Labour to compensate for the loss of Scottish seats. As voters swing away from the Conservatives towards Labour, Labour’s share of the seats in Parliament increases. Perhaps surprisingly, only relatively small swings in aggregate vote share are needed for Labour to “recover” from the loss of its Scottish MPs. Under the hypothetical exclusion of Scottish seats, Labour only requires a swing of 1.6 per cent of voters to return to its current forecasted seat share relative to the Conservatives including Scotland. This represents approximately 4.7 per cent of Conservative voters switching their support to Labour. An even smaller swing – less than 1 per cent of all voters, 1-2 per cent of Conservative voters – would result in loss of the tenuous rUK majority status we currently forecast for the Conservatives, and would leave government formation open to the vicissitudes of the coalition process. Finally, it is still plausible that Labour could still win a majority of seats in the absence of Scottish support. A swing of 3 per cent of all voters, which is about 9 per cent of Conservative voters, would result in a Labour majority. While predicting the response of rUK voters to a ‘Yes’ vote is necessarily speculative, these kinds of swings are neither implausible nor historically unprecedented.

Figure 3: Swing required for Labour recovery after Scottish independence (click on image to enlarge)

Accordingly, cataclysmic predictions of Labour’s annihilation in the event of a ‘Yes’ vote seem to overstate the case considerably. Our results certainly do indicate that Labour would find it harder to secure a majority if Scotland became independent, but we also show that plausible changes in rUK party support between the Conservatives and Labour could compensate for this shift.

One thing we are able to predict with certainty is that, regardless of the outcome of the independence vote, many new polls will be conducted thereafter, and that we will incorporate them into our model. To see what the implications of these new data are, keep visiting electionforecast.co.uk in the aftermath of the referendum.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: Ninian Reid CC BY 2.0

Jack Blumenau is a PhD candidate at the London School of Economics, specializing in the quantitative analysis of legislative politics.

Jack Blumenau is a PhD candidate at the London School of Economics, specializing in the quantitative analysis of legislative politics.

Benjamin Lauderdale is an Associate Professor in Social Research Methods at the London School of Economics, and developed the underlying forecasting model with Chris Hanretty (University of East Anglia) and Nick Viyan (Durham University).

Benjamin Lauderdale is an Associate Professor in Social Research Methods at the London School of Economics, and developed the underlying forecasting model with Chris Hanretty (University of East Anglia) and Nick Viyan (Durham University).

2 Comments