This blog post is a summary of the dissertation titled: “Claiming their right to the city: Resisting redevelopment-induced gentrification in Seoul, Korea” submitted by Earl Aldrin Burgos of the 2020-21 RUPS cohort.

The concept of gentrification has drastically changed from when it was first coined by Ruth Glass in 1960s London. It has evolved from a small-scale process seen in the neighbourhoods of Islington and the East Village to state-led projects redeveloping large communities in different parts of the world (Lees, 2019). The prevalence of gentrification in various cities globally makes the discussion of how to resist and fight it of utmost importance.

My research examines the role of the community in preventing the progress of redevelopment-induced gentrification in Cheonggyecheon-Euljiro (hereafter Euljiro), an industrial neighbourhood in Seoul, South Korea (hereafter Korea). After years of failed attempts to redevelop the area, the Seoul Metropolitan Government in 2014 decided to put the neighbourhood up for redevelopment given its decrepit state. Without measures in place to protect the neighbourhood’s merchants and craftspeople, the project was set to displace workshops of more than 50 years old and destroy generations of knowledge and expertise brought about by the neighbourhood’s years of agglomeration. As such, in exercising their right to the city, the community wants to “end redevelopment and call for the preservation and revitalisation of the neighbourhood’s industrial ecosystem with historical, industrial, and cultural values” (Choi, 2020, p.60).

Figure 1:Workshops in Euljiro (Source: Author, 2021)

By conducting in-depth, semi-structured interviews with activists, artists, researchers, and master artisans fighting redevelopment and by studying the available literature on the area, I wanted to understand the motivations surrounding the anti-gentrification movement and identify the different methods of resistance the community has used as well as their actions’ respective effects in helping stop gentrification. I utilised the classification of anti-gentrification practices put forward by Annunziata and Rivas-Alonso (2018) which categorises organised and visible resistance under four groups namely: prevention, mitigation, building alternatives, and enhancing visibility.

My dissertation aims to not only contribute to the valuable conversation of anti-gentrification practices, but also impart useful knowledge from a country that has been considered “off the map” (Robinson, 2002) and to enrich and expand the current Western-dominated literature of gentrification with an example from an Asian city. Lees (2015) highlights the absence of the Global South in the discussions on gentrification and places emphasis on “unlearning the existing dominant literature from the Global North/the West that continues to structure how we think about gentrification, its practices, and ideologies” (p.51). By documenting how gentrification is happening while at the same time being fought in Seoul, this study helps to contribute in “decolonising the field of urban studies” (Robinson, 2002, p.549).

Resistance in Euljiro was motivated by the protection of the area’s valuable industrial ecosystem, and with such focus, it contributes to expanding urban social movements and the discourse of urban rights in Korea beyond the right to subsistence to that of the right to the city (Shin, 2018). Such shift is also reflected by how resistance was led by actors apart from those who have been directly displaced by redevelopment as other urban stakeholders exercised their collective right to shape urbanisation (Harvey, 2003). While these activists engaged in diverse acts of resistance that fit the classification of anti-gentrification practices set forth by Annunziata and Rivas-Alonso (2018), institutional policies that could have helped safeguard the rights of tenants in Euljiro were clearly lacking which can be attributed to the developmental state that has put forward neoliberal urban redevelopment policies since the 80s.

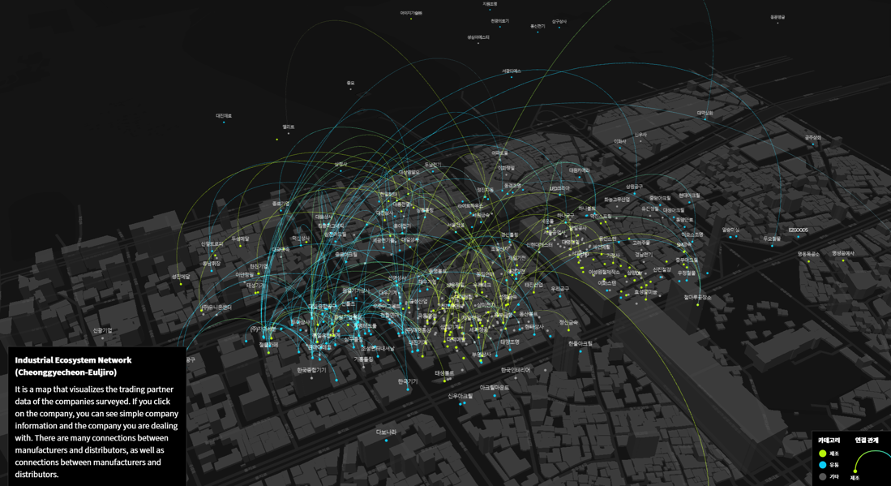

It is also important to highlight that the resistance in Euljiro is being led by young artists which is atypical of urban social movements in Korea. While historically regarded as agents of gentrification (Smith, 1986), these artists work tirelessly to unite the voices of tenants in the area and demand action from the government. In addition to engaging in conventional forms of resistance, they have injected new life in fighting gentrification by employing cultural and creative ways to achieve their goals. Some of these ways include artistically-directed protesting, putting up exhibitions on Euljiro, commissioning community art pieces, organising conferences and forums, and mapping the area’s intricate industrial ecosystem. This led to an increased awareness of the plight of the tenants which encouraged people from outside the neighbourhood to take part in the resistance and put pressure on the government to listen and act. The synergy of the different forms of resistance helped change the government’s plan and lifted various parts of the neighbourhood from redevelopment, made it possible for tenants to negotiate with developers and the government, and relocated some displaced tenants to an alternative site within the neighbourhood. The fight is however far from over as they continue to seek relocation for already-displaced tenants, ensure that the new city administration does not invalidate the years of work they have put into saving the neighbourhood, and in the long run, challenge developmentalism and change the male-dominated urban social movements in Korea.

Figure 2: Artistically directed protests for Euljiro (Source: Wikitree, 2019)

Figure 2: Artistically directed protests for Euljiro (Source: Wikitree, 2019)

Figure 3: Using art in resistance Euljiro Exhibition brochure, Flags used in Euljiro protests, Moving Messages installation, Photo Exhibition (Source: Author, 2021)

Figure 4: Social-capital@cheonggyecheon.com, a platform that visually presents the complex cooperation system within Euljiro and how it links to the national industrial ecosystem (Source: Cheonggyecheon-Euljiro Anti-Gentrification Alliance, 2021)

Evidently, the anti-gentrification movement in Euljiro has taken significant strides in helping protect the neighbourhood’s industrial ecosystem and has made more people aware that as citizens of Seoul, they should be involved in this resistance. Such success can only go so far however, if the government continues to enact neoliberal urban policies and people elect politicians who make this possible. While resistance is important, a shift from urban policies that are geared towards capital accumulation to that of inclusive and sustainable development is what is needed to prevent gentrification and further disenfranchisement of those who are already marginalised.

Lees and Ferreri (2016) call for the renewed attention of resistance in gentrification studies and emphasise the importance of understanding different kinds of resistance given gentrification’s various types to provide urban scholars valuable political and practical insights. This study helps contribute to that by providing an account of resistance to gentrification from an industrial neighbourhood in Korea and expanding the discourse on gentrification resistance in Asia given that it has not received prominent focus. With the achievements of the anti-gentrification movement in Euljiro, this study proves that it is not only interesting but important to study resistance from outside the West as it has the potential to impart lessons that can help fight the hegemony of gentrification.

References

- Annunziata, S., & Rivas-Alonso, C. (2018). Resisting gentrification. In Handbook of Gentrification Studies (pp. 393–412). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785361746.00035

- Cheonggyecheon-Euljiro Anti-Gentrification Alliance. (2021). 청계천, 을지로, 산업 유통 생태계 [Cheonggyecheon-Euljiro Industrial Distribution Ecosystem]. Retrieved from https://social-capital.cheongyecheon.com/#top.

- Choi, H.K. (2020). ‘세운재정비촉진지구’에서 ‘청계천-을지로 산업생태계’로 [From the Redevelopment Promotion District to the Industrial Ecosystem]. 문화연구, 8(2): 45-84

- Harvey, D. (2003). The right to the city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 27(4), 939-941. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2003.00492.x

- Lees, L. (2015). Gentrification. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: Second Edition (pp. 46–52). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.74013-X

- Lees, L. (2019). Planetary gentrification and urban (re)development. Urban Development Issues, 61(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.2478/udi-2019-0001

- Lees, L., & Ferreri, M. (2016). Resisting gentrification on its final frontiers: Learning from the Heygate Estate in London (1974–2013). Cities, 57, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.12.005

- Robinson, J. (2002). Global and world cities: A view from off the map. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 26(3), 531–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00397

- Shin, H. B. (2018). Urban Movements and the Genealogy of Urban Rights Discourses: The Case of Urban Protesters against Redevelopment and Displacement in Seoul, South Korea. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(2), 356–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1392844

- Smith, N. (1986). Gentrification, the frontier, and the restructuring of urban space. In Gentrification of the City (pp. 15–34). Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315889092

- Wikitree. (2019, January 17). “도시 재생이라는 이름에 재 개발 중단하라” 청계천 을지로 재개발 반대 총궐기 (사진) [“Stop redevelopment in the name of urban regeneration” Cheonggyecheon Euljiro against redevelopment protest (Photos)]. Wikitree. Retrieved from https://post.naver.com/viewer/postView.nhn?volumeNo=17610307&memberNo=21959512

20 Comments