Local adaptation measures to climate risks are laden with complexities and potential injustices. While this can be seen in both Global North and Global South contexts, it is especially true regarding the Msimbazi River Basin in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania where regular flooding exposes unplanned human settlements to severe health and livelihood risks. On the surface, recent adaptation measures created and implemented to mitigate flood risk along the Basin seem to have worthy aims, as well as a framework for ensuring that the processes and outcomes involved are just and fair. However, as our short blog highlights, the procedures involved in the displacement and relocation of local landholders, and the resultant distribution of risks and compensation, have affected the river dwellers unequally, pointing to a severe lack of ‘procedural’ and ‘distributive’ justice in the project.

Social and environmental justice challenges remain entrenched in urban climate policymaking frameworks. This is particularly thorny, given that ‘justice’ is an unstable concept, inflected by an individual’s “perception” of fairness. Thus, developing just climate policies often results in the formation of multiple realities, where some parties feel the risk mitigation process is fair, while others do not. The Msimbazi River Basin Development Project is one such case.

Foundations for Justice

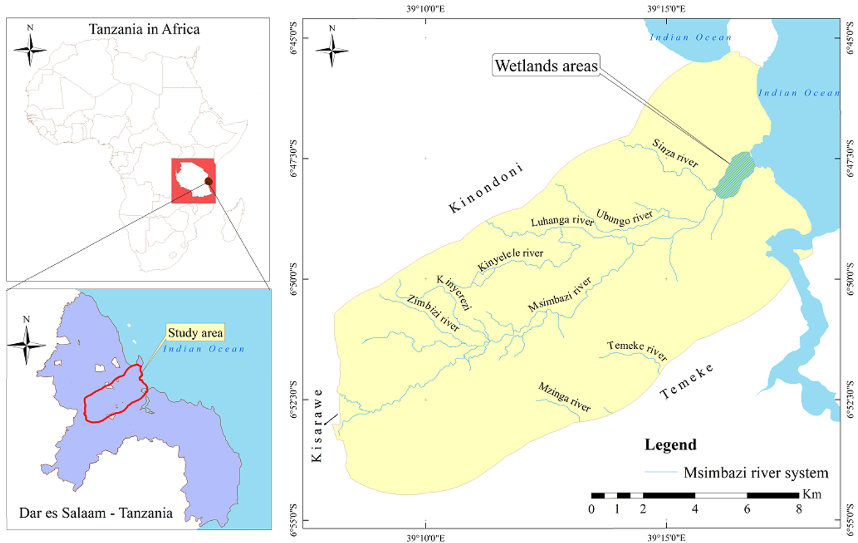

The Msimbazi River is located in the heart of Dar es Salaam, a major city and commercial port on Tanzania’s Eastern coast. For decades, it has endured severe flooding, mainly due to its poor hydraulic and infrastructural capacity, which cannot cope with increasingly high fluvial run-off. However, over the years, many officials and legal proceedings have failed to adequately declare the River Valley as ‘hazardous or environmentally sensitive’, despite concerns raised by local residents and landholders. Nor has the Tanzanian Government overcome its own lack of capacity to provide adequate amounts of serviced land for formal human settlement in a context where around 70% of urban development is unplanned. As such, despite the floods, the Msimbazi Basin has become home to thousands of informal dwellers, striving to make their lives work on the constant edge of precarity.

To reconcile historic failings and establish a foundation for justice, from 2018 local stakeholders (including the President’s Office) in partnership with the World Bank, jointly created the ‘Msimbazi Opportunity Plan’. The Plan was designed to match local community knowledge with climate science to identify and define climate adaptation solutions, including the redevelopment of the most flood-prone areas alongside the resettlement and compensation of landholders most affected by the floods. In less than nine months, 8 stakeholder workshops and 49 meetings were held, involving more than 150 individuals from 59 organisations, signalling an emphasis on participatory approaches aimed at delivering just processes and outcomes.

Procedural (in)justice

By 2022, the Plan had evolved into the Msimbazi Basin Development Project, hereafter referred to as the ‘Project’. The focus of the Project is to strengthen flood resilience by developing river basin infrastructure, re-settle ‘flood-prone communities’, and strengthen and align institutions to deliver more resilient emergency responses. This combination of prospective and corrective measures is important for effective flood mitigation interventions. However, effectiveness does not necessarily equate to fairness, as explained by Sargeant, Barkworth and Maddon’s (2020) Invariance Hypothesis, which asks whether procedural justice applies uniformly across all people, in all contexts.

In order to establish which residents would receive what level and what sort of compensation for their compulsory displacement, the Project involved four specific procedures: local community engagement, property valuation, ‘offer’ delivery, and a complaints process. From the case study we examined involving 175 landholders in Kigogo Mbuyuni, none of these steps was felt to be just or fair.

Regarding the engagement of local residents, a typical complaint was being ‘spoken at’ by officials rather than ‘listened to’:

“The Mtaa Chairman said that we would be given the chance to ask questions and seek clarity in the areas we did not understand. However, when the meeting was about to come to an end, the Government officials said they were in a hurry, so there was no time to listen to our questions.”

Furthermore, the valuation process was seen as inaccurate and lacking transparency. For sure, the valuation officers ‘walked the land’ with the plot-holders, noting the ‘unexhausted improvements’ they had made such as buildings, trees and business frames, etc. However, as many respondents noted, valuable improvements were left off their compensation offers while other less valuable items were included:

“They have written to pay me for that tree outside which is not even for fruit… and I don’t have any profit from it. Yet they haven’t written about my well that I built for more than 10million TSh… Why is this tree worth more than my well?”

Others noted that while they appreciated the valuation officers coming to their plots, the lack of transparency was concerning:

“At no point were any details given for the valuation rates”, remarked one interviewee. “They wrote down ‘tree’, but we had no idea of its value. They wrote down ‘fence’, but they said nothing of the amount.”

Further still, the vast majority of landholders we spoke with felt threatened when it came to signing their offer letters, undermining two crucial pillars of procedural justice: i.e. perceived neutrality and trust:

“On the day we were called to sign our offers… journalists were not allowed to be there, and we were threatened that if we didn’t sign, the Government couldn’t be blamed for our losses…. There were even police officers inside the room. One government officer told me that if I continued speaking to him, he would ask the policeman to escort me to the station… So I called my wife… She told me that it was better if I signed the offer. So that is what I did.”

On top of this, the complaints process also felt biased and untrustworthy. Residents felt bullied and intimidated into simply signing the offer rather than complaining. Others wanted to register a complaint, but felt powerless against the Government:

“Do I have a guarantee from the Government? No! What if those who refused to sign won’t be dealt with again and will lose their money because they have shown arrogance to the Government?”

Another landholder felt a distinct lack of trust towards those in charge who refused to stamp his complaint:

“I completed the refusal form and then asked the officials to sign and stamp it, but none of them wanted to witness it in case I decide to open a Court case. Honestly, I was worried that there might be some game going on amongst them”.

Distributive (in)justice

If the above procedures felt unjust to the majority of Kigogo’s landholders, the distribution of outcomes was devastating. Initially, when the residents heard that the World Bank would be involved, they felt assured that the compensation payments would cover the full replacement cost for their properties and help them to improve, or at least restore, their livelihoods. The reality fell short of their expectations. In fact, fewer than 15% of respondents were happy with their compensation offers, and this reinforced their negative perceptions of the whole process:

“Being valued and being listened to are two different things… By measuring the outcomes we can say that our opinions weren’t valued at all because if they were then our compensation offers would have been much higher!”

Another respondent, who had a formal property right, was appalled that no one would be paid for the value of the land:

“We thought we would be paid 100,000TSh per square meter. But on the offers, there was no land compensation for anyone… We were so surprised! I mean, let’s say, ‘yes: land is Government property’. Then where have we built our houses? On air? On water? It wasn’t fair at all!”

Indeed, for many residents, the discrepancies between what they had invested in their properties and what the Government was offering removed any hope that they would be able to reconstruct their lives elsewhere. And this held true for those who ran businesses from Kigogo or relied on its proximity to the CBD to provide their local economic opportunities:

“This place is my office. While I am here I am earning money to provide for my family. That is why I don’t want them to take it away from me by paying me such a small amount of compensation.”

In short, landholders affected by the Msimbazi Project were confused, distraught and disillusioned at the level of compensation they were being offered. Their homes, their social networks, their livelihood potentials were being taken from them, and the Government did not seem to care, as one resident starkly lamented:

“The Government has treated us in such a way that we have pains in our hearts. The money they will give us will be just enough for buying our coffins and shrouds.”

Looking ahead

In November 2023, President Samia Suluhu Hassan intervened in the compensation debacle stating that all landholders along the Msimbazi Basin should at least receive some recompense for the value of their land, even if it was to be a flat rate that didn’t reflect its true market value. Whilst, on the surface, this sounds like ‘good news’, the need for such high-level intervention serves more to expose the real, enduring procedural and distributive injustices that can arise as local actors grapple with the complexities and uneven power relations of climate risk adaptation. In the case of Kigogo, Dar es Salaam, despite the efforts of external actors like the World Bank to construct a fair and just framework, this local community on the ‘front line’ of a ‘global climate crisis’ faced displacement without due process or fair compensation. As such, questions remain regarding the means by which states can be made to take their responsibilities seriously rather than displacing them onto individuals, households and communities that are already vulnerable and under-served. Sadly, as climate change continues to disrupt the social, economic and environmental sustainability of communities across the globe, unless such issues are resolved, justice deficits in local climate-risk adaptation will almost certainly continue.