This blog post has been written by Diana Sosa, who completed MSc Psychology of Economic Life in the Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science at LSE in 2021.

In recent years, the concept of “nudge” has grown in significance in the field of behavioural science. One of the most famous and applied nudges are called “defaults”- pre-established choices. For example, some of us face the monthly default of renewing our Netflix, Amazon, or Spotify subscription; now, we could choose to cancel it but that implies a frictional process, otherwise, it will renew automatically. While some critics of nudge go around libertarian paternalistic choices- the authors of the concept, Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, argue that there is a default, planned or not, to the choices we take (Thaler & Sunstein, 2021). In this blog, I want to explore the social defaults that influence our life, and why we should be more conscious of the choices we are making.

Since we are born, depending on our sex, socioeconomic status, race, among other factors, we face a set of defaults that influence our hobbies, the way we dress, our relations, the things we consume, our goals. While we are children, that stage in life when we make most of our brain connections, we face several defaults such as the religion we will practice, the team we will support, the games we should play, among many others. In many contexts, for example, there is a default for boys to play football and this can reinforce the boundaries between male and female (Scraton, 1989).

These defaults also follow our early social connections. If we are born in an upper-class family, for example, we will be directed to grow our social capital by making upper-class friends like us. If we are born in a working-class family, there might be frictions that constrain relationships with friends from the upper classes, since in many societies there are economic, physical, and social restrictions that foster social class division.

As young adults, our role in society is getting more complex as there are more social norms to follow that go from long-term decisions to everyday choices. However, there are also status-quo choices that will guide our behaviour depending on our context. For example, the default for an average teenager in a developed country might be to keep studying. In a developing country, though, the default might be more geared toward generating income (the average years of study in developed countries is 12 years, while in developing countries is 6.5 (Winthrop, 2015)). Furthermore, the vocation we choose is also guided by our social context. As an illustration, among OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, 51% of male graduates from upper secondary vocational programs get a qualification in the field of engineering, manufacturing, and construction against 11% of female graduates (OECD, 2021). It is clear that the default of a women’s vocation is not STEM.

The next step as adults is to be productive, while we also face default definitions around success, happiness, friendships and more. In most western societies, for example, the default of success is the accumulation of capital, though this goal is highly influenced by our context and thus achieved by few. In a capitalistic economic system, the default for workers is to accept the wage and terms offered on the labour market. On average women are paid 20% less than men for doing the same job (van der Straaten et al., 2020) and CEOs are paid 351 times as much as an average worker (Mishel & Kandra, 2021).

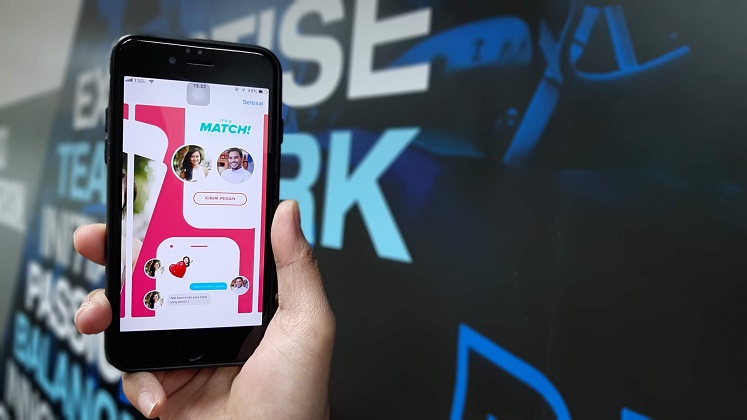

We also face status-quo options that channel our personal decisions. For instance, as Professor Paul Dolan explains, marriage and monogamy are one of the biggest norms in our society. According to the United Nations (2019) more than 70% of people between 30 and 34 are, or have been, married.

Data on same-sex marriages are not yet available in many countries. In France, however, only 3% of weddings in 2018 were among persons of the same sex (OECD, 2019). Furthermore, the proportion of households with children among OECD countries is close to 60% (OECD, 2011). Even if research shows that single women report higher level of happiness and health (Grundy & Tomassini, 2010) (DePaulo & Morris, 2005), it seems that in many countries and cultures the default as an adult is to get married (heterosexual marriage) and have kids.

But let’s recall that defaults do not constrain choices. Even if going out of the default choice might generate friction, we still have other options. We can be channelled towards a certain vocation that complies with peoples’ expectations, but we can decide to rather go for the one that passionate us. We can decide that going into an alienated job to produce and consume as an economic system indicates is not the path we want. We can decide that a heterosexual and monogamous relationship is not our thing. We can decide that we want to have a diversity of friends from different backgrounds. I am not arguing that all the defaults imposed by our context are wrong, but rather that we should be more conscious of the decisions we are taking. It is an invitation to question the status-quo we face and be brave enough to confront the frictions we do not wish to follow. I keep reflecting on the question made by Yuval Noah Harari in his book 21 Lessons for the 21st century “perhaps the real question facing us is not ‘What do we want to become?’, but ‘What do we want to want?’”.

Notes:

- The views expressed in this post are of the author and not the Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, nor the LSE.

- Post image created by the author with images sourced from here and here.

- Featured banner image sourced via Canva.

References

DePaulo, B. M., & Morris, W. L. (2005). Singles in Society and in Science. Psychological Inquiry, 16(2–3), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli162&3_01

Grundy, E. M., & Tomassini, C. (2010). Marital history, health and mortality among older men and women in England and Wales. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 554. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-554

Mishel, L., & Kandra, J. (2021). CEO pay has skyrocketed 1,322% since 1978: CEOs were paid 351 times as much as a typical worker in 2020. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/ceo-pay-in-2020/

OECD. (2011). OECD Family Database—OECD. https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm

OECD. (2019). Society at a Glance 2019: OECD Social Indicators. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/society-at-a-glance-2019_soc_glance-2019-en

OECD. (2021). Education at a Glance [Text]. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/education-at-a-glance_19991487

Scraton, S. J. (1989). Shaping up to womanhood: A study of the relationship between gender and girls’ physical education in a city-based Local Education Authority [Phd, The Open University]. http://oro.open.ac.uk/57264/

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2021). Nudge: The Final Edition. Penguin.

United Nations, D. of E. and S. A., Population Division. (2019). World Marriage Data. World Marriage Data. https://population.un.org/MarriageData/index.html#/maritalStatusChart

van der Straaten, K., Pisani, N., & Kolk, A. (2020). Why do multinationals pay women less in developing countries? World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/women-multinationals-pay-gap-developing-countries/

Winthrop, R. (2015, April 29). Global ‘100-year gap’ in education standards. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-32397212

Very interesting perspective on why we should re-evaluate our day-to-day choices and make sure we are making them with a conscious mind. Great article!