LSE Chevening Scholar Imran Khan considers the expanding debates surrounding anti-extremism discourse and Islamophobia. He argues that it is crucial to challenge religion-related violence, but that distortion and lies can be deliberately used to allow such efforts to spill over into anti-Muslim sentiment. The important work of tackling extremism must not be compromised by those who seek to create division.

On 23 April, Alek Minassian, a 25-year-old Canadian, rammed his van into pedestrians on the sidewalk in Toronto, killing 10 innocent people. Before the police could establish his identity and motivation, alt-right commentators started spreading the lie that he was Middle Eastern, brown, and therefore Muslim. It actually transpired that the attacker was an incel rebel, a misogynist group of young men who hate women because of their own inability to develop a romantic relationship.

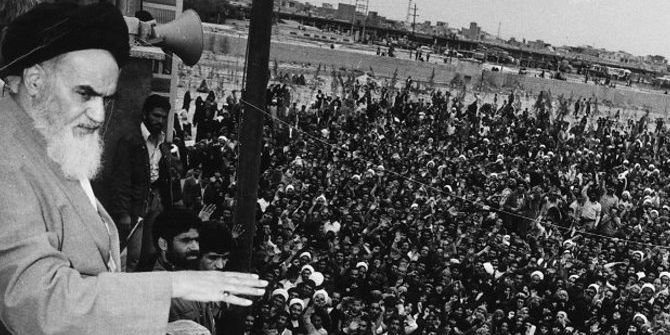

The efforts to stir anti-Islam hysteria in the wake of the Toronto attack is not an isolated phenomenon: it has become a pattern in some sections of the Western media. When a woman attacked the YouTube headquarters in California on 3 April, Islamophobes grabbed the opportunity to spew hatred against Muslims, highlighting the attacker’s Iranian origins, notwithstanding that personal grievances against the tech company were her motive.

With the rise of religious extremism across the world, people have come forward with counter-narratives as the antidote. The job of anti-extremism thinkers, writers and activists is fraught with danger, especially in Pakistan. Malala Yousafzai is a prime example of the dangers anti-extremist activists face. Malala’s work is well-known globally, but many lesser-known progressive Pakistanis, whether they are journalists, politicians or writers, challenge in their daily lives religious extremism in all its forms and manifestations. Experts, researchers and campaigners have taken up the job of countering religious extremism, and some of them do it very well.

But Islamophobia has also increased. There is a clear line between challenging religious extremism and propagating Islamophobia. Islamophobia manifests mainly in Western societies in the form of paranoia and an irrational fear of Islam and Muslims. Capitalizing on the specter of Muslims taking over the West, white supremacist groups have been gaining traction in Europe and America and some commentators, both Muslims and non-Muslims, have made lucrative think tank and media careers out of their self-proclaimed expertise in Islam and extremism. These “experts” sometimes pander to the fears and anxieties of the Western governments and intelligentsia, deliberately or unwittingly reinforcing orientalist tropes in the imaginations of the Westerners.

Anti-extremism advocacy is commendable, and more power to those who do it, whether it is against extremism stemming from white supremacy or countering an ideology using Islam as its pretext. Progressive counter-narratives are needed both in Muslim-majority countries and in the West so that the twisted and wrong interpretation of Islam, which groups like Al Qaeda, ISIS and the Taliban follow, can be defeated. However, anti-extremist discourse should not be contributing to Islamophobia. The religious extremism experts must not throw the baby out with the bathwater; and they must not alienate the organic activists, imams and ordinary Muslims who are the first line of defense against radicalization.

Religious extremism exists in Muslim communities in Western countries, providing a motivation for individuals who have gone on to commit acts of terrorism in the West. However, the majority of Muslims do not support these extremists, or else individuals like Anjem Choudary, a convicted extremist ideologue in the UK, would have far more followers in a country with a significant Muslim population. Indeed, Muslims have reported extremist individuals to the authorities in the UK and elsewhere.

Muslims are a small minority in the West. In the US, they account for roughly one percent of a total population of over 320 million. When the Islamophobia industry demonizes such a small minority, for instance by raising the specter of sharia law taking over the US, there is something fundamentally wrong. It must not be tolerated in a multi-cultural and pluralistic society.

Similarly, extremist groups that operate in Pakistan and other Muslim-majority countries demonize religious minorities, be it Christians or Ahmadis, and instigate Muslims to wage a war against the West. They hold the entire Western world responsible for the wrongs of a few Western governments. We as Muslims have the important responsibility of challenging the ideologies of hatred in our midst to protect our own minorities. Unless we do that, many would challenge our moral grounds for questioning Islamophobia.

About the author

Imran Khan is a social development consultant and researcher from Pakistan. He studied Anthropology and Development as a Chevening Scholar at the London School of Economics and will submit his dissertation later this year. Twitter: @Imran1Kh

Imran Khan is a social development consultant and researcher from Pakistan. He studied Anthropology and Development as a Chevening Scholar at the London School of Economics and will submit his dissertation later this year. Twitter: @Imran1Kh

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.