We often hear of Iran’s Islamic Revolution, but according to Anne Irfan it is more accurate to speak of a Revolution that created an Islamic Republic. Both religious and secular activists agitated for the Shah’s downfall in 1979, a fact reflected in Iran’s hybrid political system which divides power between secular and Islamic authorities. Iran is a theocracy, but to fully appreciate the country’s complexity we must acknowledge the historical and contemporary role played by secular actors.

1 April 2019 marked the fortieth anniversary of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Under this unique system, Iran is governed by a rare fusion of theocracy and republicanism. Its Head of State, known as the Supreme Leader, is a religious figure who holds the position for life after being appointed by a panel of 88 clerics. His authority is juxtaposed with a form of democracy, whereby the Iranian President – who serves as Head of Government – is elected by the Iranian people for a maximum eight-year term. Of these two wings of government, the theocracy ultimately reigns supreme; even presidential candidates must be approved by a panel of clerics before the people vote.

The complex system of Iran’s Islamic Republic was instituted in 1979, in the early aftermath of the Iranian revolution. Up until then, Iran had functioned for much of its history as a monarchy, with Mohammad Reza of the Pahlavi dynasty reigning at the time of the revolution. His rule, like that of his revolutionary successors, was autocratic and repressive; unlike theirs, it was also fervently pro-Western. The Shah’s despotism created widespread opposition to his rule, ultimately erupting in nationwide protests from late 1978. In January 1979, he relinquished the throne and went into exile. Two months later, a referendum was held on whether Iran should become an Islamic Republic. In December, the country’s new constitution confirmed the new system of rule and placed the Islamic faith at the centre of the state.

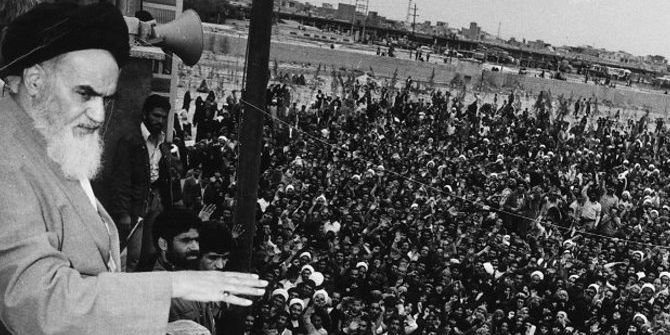

The lasting legacy of the Islamic Republic’s creation – both within and beyond and Iran’s borders – has also influenced how we tend to see the Revolution itself. Today, it is often described as the ‘Islamic Revolution’, in arenas ranging from UK university modules to The Economist to the discourse of the Iranian regime itself. Ayatollah Khomeini, who served as Iran’s first Supreme Leader from the beginning of the Islamic Republic until his death in 1989, is accordingly treated as the leader of the revolution, his image often synonymous with it. In simplistic terms this characterisation makes sense; it is true that the Iranian revolution served to replace monarchy with theocracy. Yet the historical reality is far more complicated.

In fact, it is something of a misnomer to characterise the Iranian Revolution as ‘Islamic’. Beginning in the closing months of 1978, the revolution was largely propelled by opposition to the Shah’s repressive regime, as well as despair over the country’s economic slump. The regime’s secularism – its marginalisation of clerics, its enforcement of non-Islamic laws – had long been a cause of outrage among some sectors, but it was not the primary driving force. The Iranian demonstrations encompassed large numbers of secular and leftist protestors as well as Islamists – and they found common cause in many of their grievances.

Meanwhile Khomeini, so often cited in both Iranian state discourse and the Western media as the ‘leader’ of the revolution, was not even in the country when the Revolution began. Instead he was thousands of miles away in France, having lived in exile since 1964. He returned to Iran only after the Shah had left. In other words, many of the key events of the Revolution occurred in his absence – albeit with him playing an important rhetorical role from his position abroad.

None of this is to dismiss Khomeini’s significance, or to suggest that Islam was irrelevant to the Iranian Revolution. Despite his exile, Khomeini remained an important figure, with many protestors displaying his picture and following his speeches and articles closely. Islam – specifically the Shi’a branch to which the majority of Iranians belong – served as an important cohesive force, uniting and motivating people in a way that more esoteric and elitist ideologies could not. Yet the Revolution itself cannot be explained solely by reference to Islamist politics, despite its ultimate outcome.

In fact, the diversity of the revolution was reflected in the construction of the ‘Islamic Republic’ itself. This system of governance has no real precedent in Islamic history. It is in fact a hybrid concept that was devised as a form of compromise between the revolutionary secularists and Islamists – albeit a compromise that gave ultimate power to the latter, and ensured the subordination of the former. Khomeini was the leading architect of the Islamic Republic, and he enabled its continuation by ensuring the accession of his chosen successor Ali Khamenei after his death.

As Iran marks the fortieth anniversary of both the revolution and the Islamic Republic, the country today faces numerous tensions. Its hostile relationship with the US has considered worsened since Trump took office in 2017. Meanwhile Iran’s regional rivalry with Saudi Arabia – dubbed ‘the Middle East Cold War’ – has led to ongoing proxy clashes in the civil wars in Yemen and Syria, often with a sectarian edge. As Iran continues to be deeply involved in some of the Middle East’s most sensitive conflicts, it is particularly important to grasp the complexity of its political system, and the origins of the latter’s creation. Just as the Iranian Revolution cannot be characterised as solely Islamic, nor can contemporary Iranian politics be understood purely in terms of religion. Islam, and specifically Shi’ism, is a central element of political dynamics in Iran – but it is not the only one. That remains as true today as it was 40 years ago.

About the author

Anne Irfan recently completed her PhD at LSE, on the history of Palestinian nationalism among refugee camp communities. She is currently a Teaching Fellow in Middle Eastern History at the University of Sussex, and a Guest Teacher at LSE. Email: a.e.irfan@lse.ac.uk

Anne Irfan recently completed her PhD at LSE, on the history of Palestinian nationalism among refugee camp communities. She is currently a Teaching Fellow in Middle Eastern History at the University of Sussex, and a Guest Teacher at LSE. Email: a.e.irfan@lse.ac.uk

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.