What can Pew Research Center’s recent report on Christian identity and attitudes towards minorities tell us about Europe today? Nasar Meer, who was on the panel when Pew visited LSE this summer, highlights how the report may challenge our preconceptions of interreligious tolerance. He also considers how exclusive religious identities inevitably have a political component and can therefore be influenced by nationalist sentiment.

How important are self-defined identity categories of ‘Christian’ in helping us to understand contemporary attitudes towards minorities in Europe? Recently released Pew research suggests they are quite significant, and specifically that while the majority of Europe’s Christians are non-practicing, they differ from those who consider themselves ‘religiously unaffiliated’ not only in their views on God or opinions about the place of religion in society, but also in their attitudes towards toward Jews, Muslims and migrants.

The findings from ‘Being Christian in Western Europe’, which relied on more than 24,000 interviews, suggest that Christian identities generally remain a very meaningful marker in Western Europe, even among those who seldom demonstrate religious observance through behaviour e.g., attending church services. Christianity in contemporary Europe in this respect is not merely a ‘nominal’ identity in a ‘post-secular’ age. On the contrary, it is instructive precisely because the religious, political and cultural views of both church-attending Christians and self-defined non-practicing Christians often differ from those of religiously unaffiliated adults.

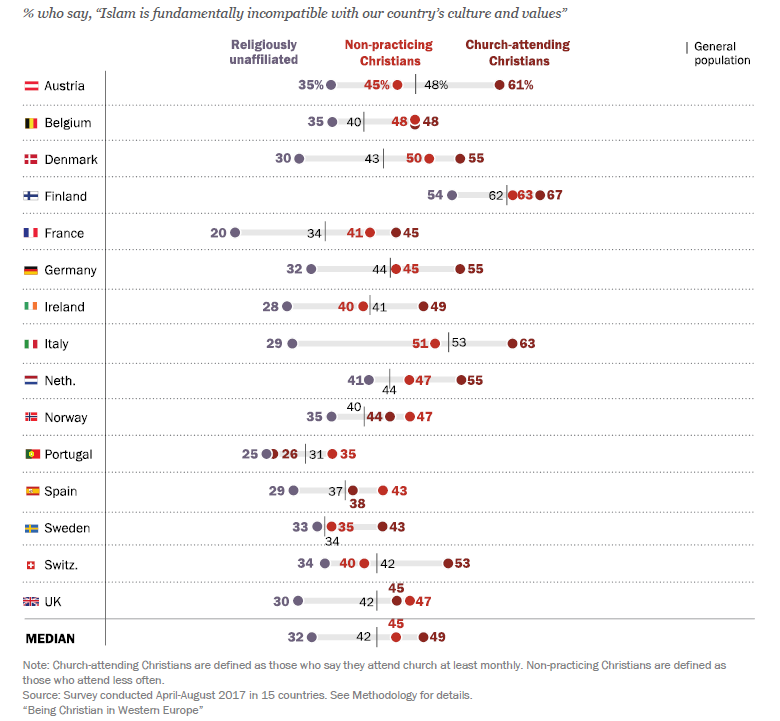

The findings prompt a number of important questions. What, for example, should we make of the emergence of a ‘clear pattern’ that both ‘church-attending’ and ‘non-practicing’ self-defined Christians are more likely than ‘religiously unaffiliated’ adults in Western Europe to voice anti-immigrant and anti-minority views? For example, 35% of churchgoing Christians and 36% of non-practicing Christians in France say immigration to their country should be reduced, compared with 21% of ‘nones’ who take this position. Meanwhile in the UK, 45% of church-attending Christians say Islam is ‘fundamentally incompatible’ with British values and culture, as does roughly the same share of non-practicing Christians (47%). Yet among religiously unaffiliated adults, significantly fewer (30%) hold this view [see Figure 1].

There is a similar pattern across Europe as to whether there should be restrictions on Muslim women’s dress in public, with Christians more likely than ‘nones’ (people who may be born into Christian households but who actively disassociate themselves from a Christian identity) to say Muslim women should not be allowed to wear any religious clothing. What are the normative implications for those who presumed there was greater common sympathy amongst people of religious backgrounds than people of none? And what, moreover, does it mean for civil society initiatives, or public policy that proceeds on that assumption? Examples include the role of the Church of England in multi-faith encounters and governmental approaches such as the Near Neighbours strategy which devolved public resources and other capital for multi-religious purposes through to the parish configuration.

Secondly, what does it mean for the hope that greater religious pluralism on a mass level would facilitate greater toleration and respect? The results point to a mixed reading here. The ‘contact hypothesis’, for all its flaws, seems to find some traction, in that knowing someone who is Jewish or Muslim seems to have a positive effect. Thus in Switzerland those who say they personally know a Muslim are 37 percentage points more likely than those who do not to disagree with the statement: ‘In their hearts, Muslims want to impose their religious law on everyone else in the country.’ Interpersonal attitudes, however, are not the entirety of religious pluralism, for this is equally bound up with views (and ultimately a sense of ownership) of national identity. This challenges us to think about the ways in which religious repertoires have translated into registers of national identity, and back again.

Can we get a better handle on the relationship between anti-minority sentiment and Christianity, and how much of this has to do with exclusive nationalisms as much as religious discourse? What we cannot discern from the data is in what direction this runs: is it an attachment to a particularly narrow view of national identity that encourages one to adopt a more exclusive version of Christianity, or it is the other way around? It would therefore be fruitful to open up a second line of inquiry which flows from these findings, and which concerns the contemporary relationship between Christianity and the sense of ownership over national identity. Ernest Barker insisted that ‘nations [have] long dreamt for their national unity in some common fund of religious ideas’. Linda Colley’s characterisation of an earlier Britain saw it as ‘a protestant Israel’, while Longley has insisted that ‘we are never going to reach the bottom of issues of national identity until we delve into the religious dimension … Religion is a weightier ingredient in these national stories than most admit’.

The Pew findings encourage us to better focus on how contemporary appeals to national identity react to minority ‘differences’. This is not quite the same approach to thinking about nations and nationalism that elaborate disputes over the creation of nations, national identities, and their relationship to each other and to non-rational ‘intuitive’ and ‘emotional’ pulls of ancestries and cultures and so on. Chief amongst these: whether or not ‘nations’ are social and political formations developed in the proliferation of modern nations from the 18th century onwards, or whether they constitute social and political formations – or ‘ethnies’ – bearing an older pedigree that may be obscured by a modernist focus.

What is most relevant is the way in which contemporary appeals to ethno-religiously marked national identities in Europe are capable of remaking themselves in response to non-Christian difference. This is not only about Christian–Muslim relations. The Pew research asked more than 20 questions about possible elements of nationalism, feelings of cultural superiority, attitudes toward Jews and Muslims, views on immigrants from various regions of the world, and overall levels of immigration. Many of these views are highly correlated. People who express negative attitudes toward Muslims and Jews are also more likely to express negative attitudes toward immigrants, and vice versa.

This corresponds with a pattern I have pointed to for some years, that the expression of anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish attitudes therefore emerges not separately but instead as a conjoined activity. This is a trend first discovered a decade ago when Pew data showed:

‘A strong relationship between anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim sentiments in the West. Indeed, among the U.S. and the six European countries included in the survey, the correlation between unfavorable opinions of Jews and unfavorable opinions of Muslims is remarkably high.’

This should not portray either Muslims or Jews as passive objects of racism, but recognise that Muslim and Jewish identities are not free of external pressures, objectification and racialization. What is required are conceptions of Islamophobia and antisemitism that are able to explain how prejudice simultaneously draws upon signs of race, culture and belonging in a way that is by no means reducible to hostility to a religion alone, and compels us to consider how religion has a social and political relevance because of the ways it is tied up with issues of community identity stereotyping, socio-economic location, political conflict and so forth.

As this survey shows, this is not an unproblematic cluster of issues to hold together, and both theoretical and empirical materials are required to address it.

About the author

Nasar Meer is Professor of Race, Identity and Citizenship at the University of Edinburgh. He is an academic advisor to the Pew Research Center.

Nasar Meer is Professor of Race, Identity and Citizenship at the University of Edinburgh. He is an academic advisor to the Pew Research Center.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.