Religion is often a salient aspect of life in the diaspora as people leave their homelands through choice or necessity to enter new communities that provide fresh challenges and opportunities to new arrivals. Keen to provoke fresh public discussion on this theme, one class at Wesleyan University has taken to public radio to share their learning with fellow citizens. Noa Street-Sachs outlines what she and her classmates learnt from this novel assignment.

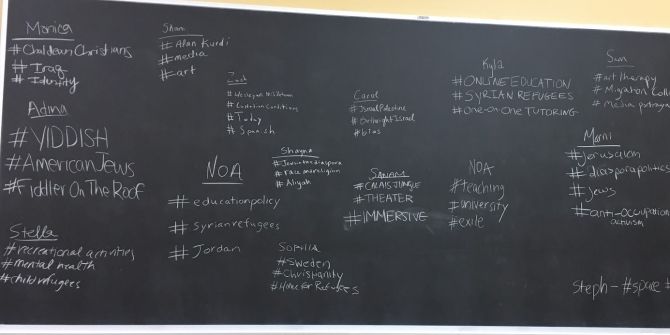

#DiasporaPolitics #ChaldeanChristians #OnlineEducation

Those were just a few of the hashtags that filled the chalkboard one Monday afternoon during a religion class at Wesleyan University called ‘Refugees and Exiles: Religion in the Diaspora’. Instead of a more conventional final like a research paper, the cumulative assignment for RELI213 was a radio segment to be aired on WESU 88.1 FM Middletown.

By November, each student had worked for a significant portion of the semester on their own segment. The topics ranged from the role of theater in humanizing the refugee crisis to a language tutoring program on Skype to a Jewish community in Uganda. Now, it was time to curate the whole show, to string together a group of eighteen seemingly disparate topics.

The exercise with the hashtags was a way to determine the bumper stickers of each segment, to find the right pairings, and to piece together a coherent sequence. After rounds of brainstorming, the class landed on the following title: Roots & Routes: Conversations on Displacement and Belonging.

Discussion of how to make content accessible to the public doesn’t often find its way into a social sciences class. There might be a nod to the importance of avoiding ivory tower discourse, but this rarely includes how precisely to do this. The practice of creating something that anyone in the greater Middletown area could take an interest in meant widening the scope of one’s target audience. The radio assignment demanded an entirely different set of skills, shifting one’s focus from weaving together concepts that emerged as central themes of the class for a professor to something more sustainable and arguably more challenging: delivering a message to an anonymous individual sitting in traffic. This process showed that there is not just a theoretical value to prying open academic discussions and putting them under the light for the public, but also a pedagogical one. There was no dancing around an idea and hoping that the reader, well-versed in the language of the class, would connect the dots. One’s work had to reach a new standard of clarity and, perhaps most importantly, stand on its own while also folding into the series. Enter: freeform radio.

Sophia Korstoff-Larsson made a segment about the Unitarian Universalist Church of Meriden, Connecticut. She explored the church’s decision to become a sanctuary space to keep individuals safe from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and both the logistical and legal challenges that the congregation faced as a result of this decision. Korstoff-Larsson spoke to pastor Paul Fleck who is co-founder of an organization called Sanctuary Connecticut. She also approached an academic with questions about the intersection between religion and political engagement, specifically religious incentives for individuals and communities to provide sanctuary. Finally, Korstoff-Larsson sat down with the church’s Reverend Dr. Jan Carlsson-Bull and got to the heart of the relationship between religion and acceptance of those fleeing persecution.

“It’s about living our faith,” Reverend Carlsson-Bull explained. “Our mission is to practice love and community, advance justice, and nurture spiritual growth. But our Unitarian Universalist principles include understanding that every person matters and that all life is connected. That’s what this is all about.”

The more theoretical portion of the class provided an essential foundation, informing our understanding of the relation between religion and the contemporary influx of displaced groups. We examined the way that religious imagination contributes to our visual consciousness, often rendering the unthreatening victim as a feminized, Madonna-like entity. Plus, through centering our discussion of Lamentations around this question of whether diaspora must be tied to a specific place, we used the destruction of the Temple as a case study for grasping the connection between exile and religion. Within theoretical approaches, we began to problematize the limitations of discourses which frame the current state of mobility for displaced populations as a “crisis”, implying an inevitability of human trauma.

While the course explored the meanings of refuge, homeland, diaspora, and exile through the lenses of religious theory, literature, philosophy, and history, the radio segment assignment presented a new challenge. “In order for your storytelling to be successful it needs to have a guiding thread running through it. An argument is in most cases the easiest way of achieving this…” read the assignment itself. “One way of thinking about the argument is through a question: WHY are you telling the listener this? WHY is it important?”

Korstoff-Larsson spoke of this. “Making this radio segment allowed for a more direct engagement with the material, especially through interacting with some of the individuals involved in my topic. I learned how to gather information in a firsthand manner, and then find background/supplementary information to support this information.”

A successful segment includes multiple voices and perspectives. My topic was the double-shift educational policy in Jordan, a product of the effort to incorporate the influx of Syrian refugees into the school system. Within the double-shift system, the school day is split into two parts: Jordanian students mostly attend the morning session while Syrians attend the later one. This impacts the quality of education for both groups as well as their social segregation. The voice I tried to center in the segment was that of a 31-year-old Syrian woman living in Amman with her two children. Her discussion of some of the real shortcomings of this double-shift system became pivotal to the segment.

It was the very fact that the medium of the assignment was radio that urged me to go beyond academic analyses. While the radio format initially posed an unfamiliarity that was an added challenge, it was ultimately a liberating type of research that allowed for more breadth and depth. The sources I could – and should – draw from were not just peer-reviewed Jstor articles, but rather the result of casting a much wider net. I could contact NGOs, parse through story maps, and most importantly, hear from individuals’ lived experiences.

The early stage of the assignment was familiar to preparing an analytical paper. It required honing in on a topic and narrowing it to a manageable, perhaps more-specific-than-expected scope. From that point onwards, the process bore little resemblance to other academic exercises. Academic jargon – from biopolitics to necropolitics to heterotopias – had no place in a strong radio segment. These were examples of analytical tools which were entry points into dialogue surrounding logics of exile, displacement, and removal. They unearthed the ways that capitalism hinges on the movement of goods without a matching acceptance of the movement of individuals that accompanies a globalized economy. They were vehicles for understanding the constellation that can connect religion with both acceptance and persecution and exile with displacement. But they were not tools for communicating this understanding. Korstoff-Larsson discussed these overlaps.

“Religion is an important part of conversations surrounding refugees/exile/displacement because it is often a prevalent factor in the life of one who is experiencing refuge/exile/displacement,” she wrote. “It can be a cause for one’s need to leave, but also a part of one’s integration (or lack thereof) somewhere new. Religion plays a large role in identity shaping and community building, which are two primary aspects to refugees/exile/displacement, as these two things are often dismantled in such a situation, with the need of being reconstructed.”

About the author

Noa Street-Sachs is a graduate of the College of Social Studies at Wesleyan University, where she studied government, history, economics, and social theory and received a certificate in cultural and critical theory. Her interests include refugee rights, immigration law, and criminal justice reform. She can be reached by email at nsteetsachs@wesleyan.edu or LinkedIn.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.