The use of social media and instant messaging platforms has been more important and influential than ever during the COVID-19 pandemic. How has this shaped information sharing within religious communities now that public gatherings are heavily restricted? Tamim Mobayed sees a democratising trend through WhatsApp communication. He also describes how the nuance of local and specific religious rulings can get lost as messages are forwarded on a global scale.

Like all sections of society, Muslims are increasingly taking to WhatsApp for their news and information sharing. Medical advice centred on stopping the spread of the virus, such as social distancing, working from home, and the shifting of educational spaces towards being online, strengthen the relative viability of WhatsApp and social media platforms for garnering information. The integration of our offline and online lives has been growing considerably, with the pandemic seemingly accelerating our reliance on the virtual; my own screen time, considerable on quiet days, has shot up by 53% since the pandemic set in.

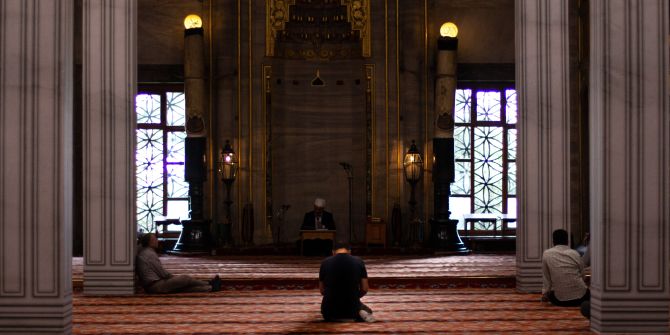

While the medium might not entirely be the message, it does influence it. When it comes to dissemination of religious information, there are a few factors that make WhatsApp quite radical. The level of democratisation is noticeable, particularly given the enduring legacy of hierarchies within religious spaces. Muslims often cite the story of the Caliph Umar being corrected by a woman in public as an example of the need for direct holding to account (commanding right and forbidding wrong) of the powerful, as well as the undertones pertaining to gender equality, at the very least in the realm of establishing truth. This ideal continues to elude Muslims today, with Muslim women still having to fight for the most basic of rights, including having their own spaces within mosques. These obstacles to openness are not as readily found within WhatsApp, with gender differences being less salient in a world where one can only be identified by their chosen username. Moving away from gender, another equalising feature comes by way of removing the benefits of charisma, public speaking skills, body language utilisation and other communicative signals that tend to dominate persuasive processes. Does this aid or hinder the religious snake oil salespeople and zealots?

The science of establishing the authenticity of hadith places fundamental significance on the character of the individuals within the chain of narration; one weak link within a narrative chain can render an entire chain questionable. These painfully exhaustive processes are absent; instead, WhatsApp has a recently added feature that flags a message as having been forwarded. What it lacks in robustness, it makes up for in speed, and speed is a critical factor in the face of a pandemic. Speed is also a critical factor when fanning the flames of religiously-motivated riots.

The spread of information across communities and geographic boundaries also carries implications that stem from localisation and specificity. Fatwas are legislative rulings made by scholars and are often intricately particular, and applicable to a local context, or even an individual within a specific context. WhatsApp sharing often disregards this, with rulings that are shared carrying no such conditions, with the one making the ruling potentially knowing nothing about the context where their ruling reaches. While this spread of information carries intellectual benefits, not least of which, is the exposure of many to alternative opinions, the absence of context in shaping a ruling can be deeply problematic, and indeed, is often a symptom of hard-line fundamentalism.

Regardless of an assessment of the utility the marriage between social networking apps and religious information, the marriage will certainly be an enduring one. It remains to be seen how productive or problematic it will be. On a human level, WhatsApp continues to be an informational spring that the faithful turn to, particularly in times of social isolation, self-containment and quarantine.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.