The suspension of public worship has been strictly adhered to in the Faroe Islands, as its entire population of 50,000 would be highly vulnerable to an outbreak of coronavirus. Jan Jensen reports that some churches have transitioned to online services more easily than others. He also observes how the slowed pace of life has prompted Faroe Islanders to reflect on the role of the church in the modern world and its need to more effectively reach out to wider society.

On the evening of 6 March 2020, around three hundred women were gathered in City Church, a neo-Pentecostal church in the center of Tórshavn. This small city is the capital of the Faroe Islands, a group of islands in the middle of the North Atlantic with a total population of around 50,000. At this particular moment around 6pm, the weekend’s Women’s Conference, which is the church’s biggest event of the year, was being inaugurated by Elsebeth Mercedes Gunnleygsdottir, Minister of Social Affairs in the country. Six days later, Elsebeth was on national television together with Bárður á Steig Nielsen, Prime Minister, as well as other government officials to inform the Faroese public about the government’s measures in regards to the coronavirus outbreak.

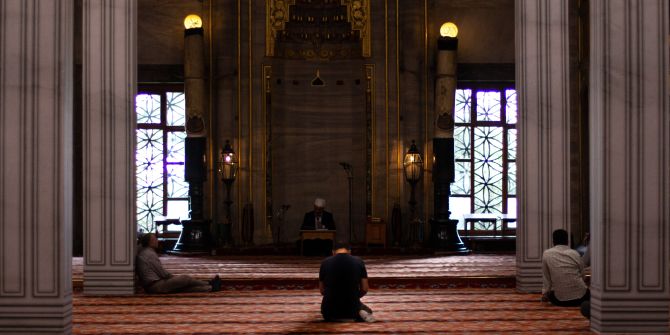

Much as many other European countries, the Faroe Islands moved quickly once the first few cases of the coronavirus had been confirmed in the country. Taking the government’s measures to heart, all churches suspended their gatherings from day one. At a time when religious gatherings have become an important factor in the spread of the coronavirus in many places around the world, the fact that all churches in the Faroe Islands chose this co-operative path in relation to public authorities is remarkable. It is not hard to imagine that in a small country such as the Faroe Islands where around 25% of the population attends Christian services every week, these gatherings could easily have become a hotbed for the spread of the coronavirus. However, at the time of writing, there are zero confirmed current cases in the country, the last confirmed case being on 22 April.

The choice of suspending all in-person church services meant that most churches moved their activities online, with some churches being well-equipped to do so (City Church for example already had an elaborate technical set-up used for live streaming prior to the coronavirus outbreak). Others had to quickly figure out the necessary technical requirements for these kinds of services. In many cases, it seems that these online services have been able to fulfill the needs of congregants, while for many it has been a poor substitute to the real thing. Perhaps especially in those churches that emphasize personal experience, such as Pentecostal and Charismatic churches, not being able to attend services in-person has meant that central elements of a Christian life such as musical worship have not been possible. On the other hand, online services in different churches have seen an “attendance” many times over the amount of people that attend in person on a given Sunday.Many people have used the lockdown and the proliferation of online services as an opportunity to check out what different churches are doing rather than only looking at streams from the churches with which they are usually affiliated.

Perhaps the most important development among many of the people I have been able to speak with, however, has been the strong sense of relief that they have felt during the time of coronavirus. While the state Lutheran church has a corpus of paid clergy, most so-called “free churches” (i.e. not part of the state church) run almost entirely on voluntary labour, with perhaps two or three persons employed with a salary (usually pastors). This means that many responsibilities within the churches tend to fall on a few central persons, with many ancillary contributors carrying out different activities within the churches.

What the coronavirus outbreak has laid bare among Christians in the Faroe Islands is the forms of labour that most people are enmeshed in, and during the months of intense lockdown, it has been a time of reflection on the relationship between work, church, and God. Since voluntary labour in churches always runs the risk of ministry burnout, the lockdown came as a welcome break from the intense activities of everyday life for many people. In a country with almost full employment and where most households are dual-income, this means that most church volunteers already have a weekly schedule that leaves almost no time for quiet relaxation or reflection.

This has led to many people in the Faroe Islands using the coronavirus lockdown as a welcome opportunity to not only get a break from the hustle and bustle of everyday life but also as a chance to re-evaluate what church life is, or what it is supposed to be. What the lockdown has laid bare is that much of the effort that goes into organizing and volunteering is often based on routine, whereas the ideal church is one of intense intentionality. It bespeaks a development among many “modern” churches that sees the role of the church as first and foremost to speak into the needs and milieu of the adjacent society. By this logic, if the church struggles to attract new members, it is not because of a “fallen society” that has turned its back on the message of the Bible. Rather it is that the church itself has not been able to stay relevant and to shape itself based on the current needs of society.

By the same logic, a central question becomes “do we want to go back to the way we have done things prior to the coronavirus lockdown”? Rather than a loss of tradition and/or the proper way to “do church”, the lockdown has in some ways become a catalyst for churches to re-shape their practices, and to move towards what they wish they could be, but which many people feel has not previously been possible. For example, leaders of many churches feel that they were not well equipped to offer practical help to vulnerable members of not only their own churches but of society in general, and this has led them to establish networks that can easily be mobilized if Faroese society should find itself in a similar situation again in the future.

Since mid-June, Faroese society has gradually opened up again, with society’s wheels again accelerating towards previous levels. Large gatherings are no longer prohibited, and most churches have once again started filling their halls with eager crowds. Time will tell whether the lockdown and its opportunities for self-reflection will have a lasting impact or whether things will go back to normal as they were prior to the coronavirus outbreak.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Thanks for the interesting article, we found it as we were looking for flights to Torshavn where our son lives. We pastor a small House Church and have links with Faroese churches curious about our experience of church. Will explain more if you are interested. Regards and Blessings Helen and Simon Glyn – Davies.

–