The coronavirus pandemic continues to highlight the enduring power of the global religions and the consequential role played by religious leaders and communities in either heeding or ignoring public health advice. John Blevins sets the scene for us, highlighting the unique challenges faced by developing countries and the pressing need for a coordinated global response that recognizes and utilises religion’s social capital.

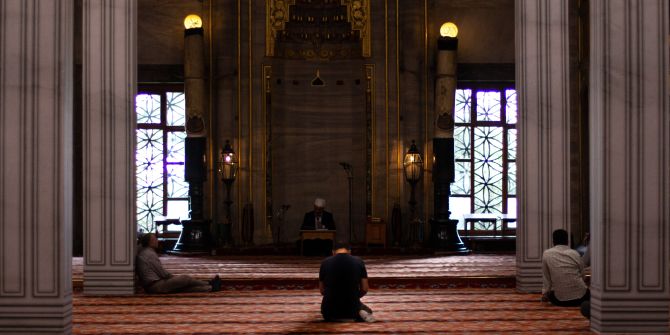

Religion is a potent, long-standing, and pervasive social force. The social power it generates can be used in helpful ways to slow the spread of COVID—19 or in harmful ways that hasten the spread of the virus. Religious gatherings have been key drivers of the spread of the disease. Infections tied to services held by a Christian group in South Korea in early February formed the epicenter of the outbreak there. Infections that occurred during a four-day pilgrimage to Malaysia in late-February by 16,000 Muslim faithful are believed to have spread the virus to six other countries, a case described as “the largest known viral vector in southeast Asia”. In the United States, transmission among mourners attending a Christian funeral has left Dougherty County, a rural county in the state of Georgia, with a per capita infection rate more than two times higher than that of New York City (as of 1 April). Despite a handful of religious leaders refusing calls to cancel services and other gatherings, most faith communities have cancelled in-person events and have quickly established a variety of platforms and models for online worship and pastoral care and a Facebook group of over 6,300 clergy representing various traditions across the world are sharing resources for how their masajid, temples, and churches can support infection-control measures.

There is growing consensus, however, that such measures are simply not helpful for individuals, households, and communities in many lower- and middle-income countries where the idea of voluntary quarantine or stay-at-home mandates fail to consider housing conditions or economic needs. Religious leaders can play an important role in these communities because they are often perceived as more trustworthy than health officials. As such, they can be important sources for gathering community members’ insights and can offer important feedback on the feasibility of adapted guidance that reflects reality on the ground in many parts of the world. To do this, religious leaders in those countries will have to rely on different online and social media platforms than those available to their peers in Europe and North America because the bandwidth and hardware required for videoconferencing are not available for most people. Those leaders will likely draw on the important lessons they learned during the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak. In that outbreak, coordinated inter-religious efforts complemented massive social messaging campaigns through SMS and WhatsApp platforms to provide relevant and contextually acceptable health information to millions of people across the west Africa region. Replicating those kinds of structures and campaigns will be crucial in the COVID—19 response.

Given these examples, here’s what we know today: religion has impacted and will continue to impact the COVID—19 response in myriad ways. It has spread and will continue to spread the disease through continued religious gatherings that ignore public health advice. It has slowed and will continue to slow the spread by offering sound health information framed in ways that are intelligible, culturally and theologically relevant, contextually practical, and trusted. There are limits, however, as to what we can know at this time:

- What will effective and practical models for prevention/mitigation look like as the virus spreads across low- and middle-income countries? What role will religious leaders play in developing and disseminating those messages?

- If many citizens in some parts of the world insist on gathering for religious events—especially as important religious events such as Easter and Ramadan loom on the calendar in April—which approach will contribute to an outbreak response that is more effective in the long run: enforcing such prohibitions with firmer measures or opting for a collaborative approach through modified, smaller gatherings so as to challenge misinformation and rumors and defuse the potential for unrest ?

- How will we start to loosen restrictions after the first wave of infections has passed, even as we guard against a new wave? What role will religious leaders play in that effort? Just as the outbreak has been phased as the virus spreads around the world, so too will the recovery response. As Europe and North America emerge from this first wave and assess its impact, the temptation of elected officials and markets to overlook the impact of the outbreak in low- and middle-income countries will be strong; religious leaders will play an important role in reminding those of us from these regions that we are, indeed, inter-connected and that we have an obligation to work in global partnerships to respond to the needs of all and not only to the needs of those from our own countries.

There are existing, active, and effective networks of religious leaders and communities working in partnership with global, regional, national, and local public health initiatives. Those faith networks must be essential parts of the robust, sustained, multi-sector response to COVID—19 being built right now. Their expertise is needed, their distinctive role as trusted messengers is needed, and the life-saving health services they provide on the front lines are needed. In return, the individuals and organizations in those networks need our support. They need funding. They need advocates who will take their contributions seriously. They need to be part of the leadership making decisions. I started this article by noting that religion is a potent, long-standing, and pervasive social force. The social power it generates can be used in helpful ways to slow the spread of COVID—19 or in harmful ways to hasten the spread of the virus. It is imperative that we channel its power towards the common good.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Terrific. Well done. R

Thank you for this blog entry. I am working in India on covid19 and fake news. Religion is a very important factor. Can you please point out to some of the “active, and effective networks of religious leaders and communities working in partnership with global, regional, national, and local public health initiatives” in South East Asia, especially India?

Hi Antonella,

I’m the author of this piece. I wasn’t clear about your reference to fake news in the first sentence so I hope this reply addresses the primary focus in your comment; if it doesn’t please feel free to reply again and I’ll try to address it.

In regard to active and effective networks, here are some global religious bodies working to address the pandemic through their national and regional partners:

Islamic Relief Worldwide

https://www.islamic-relief.org/category/appeals/emergencies/coronavirus-appeal/

The World Council of Churches (Christian Protestant)

https://www.oikoumene.org/en/resources/documents/covid-19

Caritas Internationalis (Christian Roman Catholic)

https://www.caritas.org/what-we-do/conflicts-and-disasters/emergencies/covid19/

The Joint Learning Initiative on Faith and Local Communities (a global, inter-religious network of faith-based organizations, researchers, and health and development practitioners)

https://jliflc.com/covid/

Arigatou (an international inter-religious organization focused on addressing the specific vulnerabilities facing children, especially the children living in poverty)

https://arigatouinternational.org/en/response-to-covid19

I’m not sure where you are in India but you might find partnerships and resources through the national partner bodies of these global organizations. These are some examples (not exhaustive):

The National Council of Churches of India (the national partner body to the World Council of Churches)

https://ncci1914.com/02-03-04-constituent-response/

Caritas India (the national partner body of Caritas Intrenationalis)

https://www.caritasindia.org/covid-19/

Islamic Relief India

https://www.islamic-relief.org/category/where-we-work/india/

Various public health organizations are working in collaboration with faith partners, including:

The World Health Organization

https://www.who.int/teams/risk-communication/faith-based-organizations-and-faith-leaders

Coordination between governmental and civil society health responses needs to be coordinated at the national, sub-national, and local levels to be effective and respectful of national laws and policies. I can’t say much specifically about this coordination in India because I am not actively working there on the COVID response. In addition, it is also quite clear that religion can be used to further cultural divisions, often as part of political calculations. This has obviously all over the world and is now happening in India.

The website of the program I direct at Emory University (US) has a variety of COVID-19 resources from various religious traditions:

http://ihpemory.org/covid-19-resources/

Again, I hope this addressed the issue you raised in your comment; if not, let me know.

John Blevins