To progress towards sustainable development, each society’s unique culture, and how this influences individual behaviour, must be better understood from a post-colonial perspective. Romina Istratii writes that efforts towards gender equality must be made within the context of a religious society’s culture, and not from imposed secular assumptions.

Concomitant with the gradual secularisation of western science and thought, late twentieth-century gender-related development scholarship typically dismissed religious belief and knowledge. When these parameters were considered, they were usually perceived as loci of female subordination. This is not unrelated to historical tendencies within western feminist theology and gender and religion(s) studies that appraised religious traditions – especially Christianity – through a “hermeneutics of suspicion”. It also parallels earlier paradigms within international development that regarded religion either as a hindrance to, or irrelevant to, development practice. Little reflection was given to the fact that societies presented distinct cosmologies that could be faith-based and that religious beliefs could be influencing perceptions of subjectivity and gender relations in unique ways that development studies and research could not afford to neglect.

In recent years, where religious and gender studies in regards to development have multiplied and have become more nuanced, main theoretical premises regarding ‘gender’ or ‘religion’ seem to persist. While gender and related concepts continue to be disproportionately informed by feminist metaphysics framed in western epistemology, religions are still depicted as conducive to gender inequalities, albeit increasingly also as potential instruments for addressing gender-related issues. However, the latter discourses tend to place emphasis on religious leaders, organisations or institutions, with the implication that ‘religion’ is filtered through a persistent western epistemological framework that conceptually isolates faith from wider cosmological systems shaping human reasoning and vernacular life. This conceptualisation cannot account for the intricate ways in which religious parameters are accommodated in diverse belief systems and their multi-dimensional interfaces with socio-cultural and gender norms, attitudes and human behaviour in distinct societies.

Drawing from many years’ experience in gender-sensitive development research in Africa, I have proposed that gender-related issues should be approached through a more comprehensive and people-centred study of local metaphysics of subjectivity to consolidate a gender-sensitive analysis from ‘within’. While most societies might typologize individuals by gender identity, it cannot be assumed that individuals living in very diverse contexts are valued primarily or exclusively by their gender, that this is uniformly hierarchical, or that it is the most salient determinant of societal problems, such as conjugal abuse, not least because of multiple ways in which human subjectivity or in this case abusiveness can be understood and appraised in different belief systems. In religious communities these metaphysics will likely interweave with religio-cultural parameters in intricate and non-uniform ways, which makes it challenging to establish direct associations between norms or attitudes that hinder egalitarian or healthy relationships with a concrete religious, cultural or other isolated parameter.

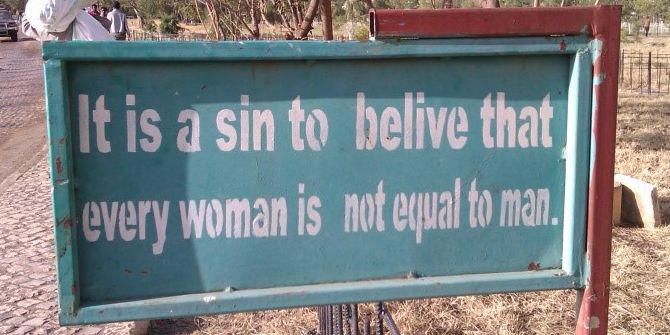

Describing these interfaces within a more comprehensive cosmology-informed analysis can foster a move toward a model of sustainable development that is much needed in our post-colonial times. This approach would seek to understand, describe and potentially address gender-related problems through discourses and resources emerging from within local worldviews that could have more credibility and influence with local populations. Admittedly, development practice has in recent times been dominated by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) discourse and priorities. A recent AHRC-funded conference on Religions and Development organised in Ethiopia showed that local organisations have felt compelled to engage with the SDGs, but suggested also that this discourse might not adequately capture local complexities and priorities. Some participants noted that the SDGs could have included as an additional goal the protection and promotion of local knowledge, mentioning specifically religious values and spiritual priorities. Others observed that gender equality or relevant terms were vaguely defined in mainstream documents or did not consider local religio-cultural beliefs and understandings regarding gender relations. However, local organisations had to engage with local gender knowledge and beliefs in order to converse properly with religious communities and to inspire necessary attitudinal or normative changes within the valued normative system.

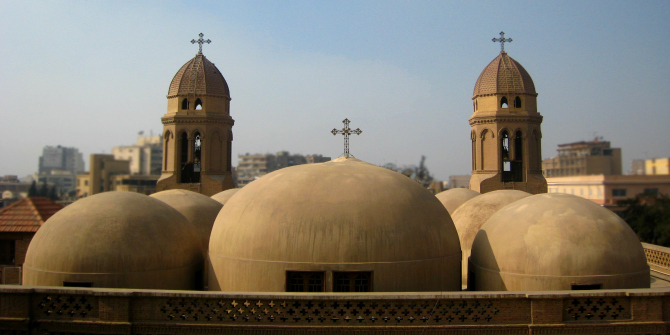

At the same conference I presented my recently completed ethnographic study of conjugal abuse from the countryside of Aksum in Northern Ethiopia, which provides more insight into these realities. The study was sensitive to religious parameters in order to account for Ethiopia’s influential pre-Chalcedon Christian tradition that was officially embraced by the rulers of the Kingdom of Aksum in the fourth century. The Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahәdo tradition, which developed intimately with the socio-cultural surroundings and political history of Ethiopia, appears to have met with realities and attitudes around conjugal abuse, but no available study of domestic violence has accounted for this religio-cultural context. Subsequently, the study explored whether and how gender ideas became salient in discourses of conjugal abuse from the insiders’ religio-cultural perspective. This meant combining a theology-informed analysis of Church teachings on gender relations, marriage and conjugal abuse with an ethnographic exploration of local metaphysics of subjectivity, gender relations and religious experience within marriage.

The research revealed that research participants considered conjugal abusiveness to be wrong by standards associated with both their culture (bahәl) and with their religion (haymanot), a distinction that participants readily made. However, an underlying tolerance of the problem was visible in institutional and socio-cultural norms and practices that were described as ineffective in dealing with women’s reports of conjugal violence, as well as most women’s endurance and secretiveness when they dealt with an abusive partner. Such attitudes and realities seemed to be underpinned by a host of socio-cultural, practical and psychological factors, but they were enforced indirectly and in non-uniform ways by some clergy discourses and personal faith, co-acting with deeper metaphysics of individuality that were not without gendered dimensions.

At its essence the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahәdo faith has been premised on an apostolic message of healing the fallen human nature and restoring relationship with God by cultivating love and meekness. However, an Old Testament heritage or orientation has perhaps been stronger, not unrelated to the indigenous Cushitic-Semitic cultural underlayer in which the Church tradition developed. While the Church has upheld ontological and spiritual equality between males and females, it has also preserved what might be considered gender asymmetrical practices, which are even more pronounced in the societal rules and religious norms of the laity. The rural clergy in Aksum were generally found to oppose pernicious culture-condoned practices and to mediate conjugal abuse situations in ways that usually favoured the victimised party. Still, the unclear demarcations vis-à-vis folklore gender and marriage ideals made some of the clergy’s discourses at times conducive to an enforcement of understandings and norms associated with local forms of conjugal abuse. Not unrelated to historical weaknesses affecting the traditional Church education, the average priest (as opposed to church teachers and more learned clergy) displayed limited exegetical training and was unprepared to pronounce religious teachings within contextual hermeneutics that were sufficiently informed by apostolic marriage theology.

These complex overlaps between religious and socio-cultural parameters in clergy discourses were also visible in the discourses of the laity. Despite differentiating between faith and culture, the vast majority of rural residents did not essentially distinguish between folklore norms and their deeply cherished religious tradition and were suspicious of any deviation from their religious lifestyle as they knew it. This had implications for how they responded to social norms, including those associated with gender asymmetries or other pernicious conventions that related to conjugal abuse. For example, virtually everyone affirmed that the rigid gender-based segregation of married life, which was associated with much conjugal conflict and abuse, was cultural and not religious. Similar statements were made regarding the regular mahbär gatherings convened typically for the veneration of saints, and especially their component of alcohol consumption which was associated with some manifestation of husband abusiveness. Still, such pronouncements did not displace prevalent discourses that considered the valued religious tradition and local religious norms to overlap, essentially contributing to the unreflective preservation of some pernicious conventions.

Simultaneously, research participants were embedded in a folklore belief system that centred on the natural and acquired proclivities of the individual, an individual who was imagined to be situated in a spiritual battlefield between good and evil. This implied that individuals were considered responsible for their abusiveness, but not entirely able to always avoid effectively due to external overpowering inducements (such as alcohol or Satan) combined with what was understood to be a weak faith-based conscience (ḫәllina) among some. Folklore-gendered underpinnings to how people understood human ontology and abusiveness in interaction with spirituality seemed to enforce different responses toward female and male abusiveness, fostering a tendency to want to justify abusive men and to expect non-confrontation and forbearance on the part of the women.

Previous domestic studies from Ethiopia have identified among other things the importance of raising awareness regarding gender-asymmetries, strengthening education for both spouses and consolidating the legal and institutional framework for dealing more effectively with conjugal abuse. While desirable, such strategies in Aksum would be mediated by local people’s responses to social norms vis-à-vis their valued religious tradition, as well as fundamental beliefs about the cause and reversibility of male abusiveness. Any future intervention would need to integrate the local clergy appropriately in order to reverse harmful tendencies perpetuated via insufficiently nuanced theological discourses, but also to leverage on the force of their spoken apostolic messages to encourage a consideration of folklore norms by the laity in a more critical light. It would also necessitate developing counter-discourses to cultivate new beliefs that abusiveness need not always be irreversible or uncontrollable, which the Church’s theology of healing and achieving likeness to God could readily contribute to.

Such insights cannot encapsulate the complex study that was achieved in Aksum, but they are outlined here to emphasise the urgency for suspending generic conceptualisations of gender, religion and their interfaces in cross-cultural development practice. Both the recent conference held in Ethiopia and studies such as these underline the need for relying more on local belief and knowledge systems to identify how gender-related societal issues could be effectively understood and addressed within their local contexts. If these local contexts and knowledge systems are intricately embedded within religious traditions that are valued by local populations, religious parameters will need to be carefully analysed in their socio-cultural matrix and be harnessed appropriately as part of remedial interventions.

About the author

Romina Istratii is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Religions and Philosophies at SOAS, University of London. She has previously completed gender-sensitive research in a number of African countries as a Thomas J. Watson Fellow and has worked as a researcher and consultant in the sector of international development for more than seven years. As a critical thinker and practitioner from Eastern Europe, she has been working to attune theory and practice to non-western and non-secular epistemologies which have been neglected in the prevalent western epistemological framework.

Romina Istratii is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Religions and Philosophies at SOAS, University of London. She has previously completed gender-sensitive research in a number of African countries as a Thomas J. Watson Fellow and has worked as a researcher and consultant in the sector of international development for more than seven years. As a critical thinker and practitioner from Eastern Europe, she has been working to attune theory and practice to non-western and non-secular epistemologies which have been neglected in the prevalent western epistemological framework.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

1 Comments