In claiming religious freedom as a justification to act contrary to public health advice, some conservative Christian leaders in the United States are choosing to risk American lives so that their congregations can attend to their spiritual needs. Though most Christian communities have suspended traditional worship in adherence of social distancing guidelines, David C. McDuffie sees the defiant behaviour of the minority as rooted in a common supernatural understanding of Christian duty. A more naturalistic theology, he argues, wouldn’t allow for this subversion of the public good at a time of national crisis.

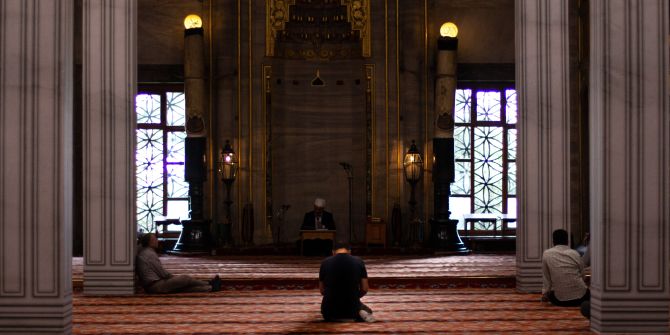

Amid the cultural upheavals of the last few months as COVID—19 has swept the globe, the effects that the pandemic is having on religion are receiving a lot of attention. Images of empty worship spaces and discussions of the nature and necessity of online religious observance have become commonplace. In the United States, most Christian communities have followed the advice of public health professionals and suspended traditional worship for the time being. However, there is a small, albeit significant, minority, who have resisted stay-at-home orders and social distancing guidelines. Representing a combination of anti-science supernatural religion and conservative politics, this faction of conservative Christians has insisted on the right to gather for worship in the name of religious freedom and, in the process, has become a significant threat to public health.

In an article aptly titled “When Faith Threatens Public Health” and published on 24 March when stay-at-home orders and social distancing restrictions were increasing exponentially throughout the country, Professor Candida Moss highlights the inevitable dangers present when conservative religious leaders prioritize religious observation and personal salvation over sound public health policy. As she notes, these dangers are amplified when such views are coupled with support from government officials. On the eve of Easter, a holiday marking the culmination of the Christian year, the death toll from COVID—19 in the United States exceeded that of any other country in the world and states of emergency were reached in all 50 states for the first time in American history. Yet defiance among some conservative Christian leaders – with the aid of several state governments – continued, with claims that religious worship is an “essential” practice and protected by Constitutional religious freedom. While small in number, the threat that these Christian leaders and communities pose to public health is not. In fact, there is now evidence that religious communities who insist on continuing to gather for worship are leading contributors to the perpetuation of COVID—19, a virus that has infected 3 million people and resulted in over 200,000 deaths worldwide.

Religious leaders are integral to effectively addressing this issue. The importance of religious authority and leadership in a public health crisis has been well established, particularly in relation to conveying important scientific information that members of religious communities may be reluctant to accept from scientific experts. This is all the more important considering that focusing on a political strategy alone to promote effective public health practice risks failure given the current political climate in the United States. In the current situation, certain state governments have already shown a willingness to see this as an issue of religious liberty and to favor religious communities’ right to gather over the social distancing requirements necessary to protect public health. At the federal level, the Trump administration has consistently appealed to the conservative religious base that voted overwhelmingly for him in the 2016 election. Evidence of this can be seen in his misguided comments on filling churches on Easter against all of the best advice of public health officials.

While it has become more of an imminent concern during the current pandemic, the alliance between conservative Christians and the Trump administration concerning hostility to scientific experts has moved in lockstep from the administration’s attempts to deny human responsibility for climate change to the current mishandling of the response to COVID—19, which has undoubtedly cost thousands of lives. Cultural influence and contributions to policy on climate change and coronavirus, in addition to the role played in promoting the anti-vaccination movement, make clear that religious influence in American politics is responsible for putting the health of the American public at risk.

Therefore, it is imperative that American religious leaders who support sound public health policy criticize not only bad public policy suggestions but also the claims of religious freedom that put America’s healthcare system and particularly the most vulnerable (the elderly, immunocompromised, and those with underlying medical conditions) in danger. Freedom of assembly does not include the destruction of property. Freedom of speech does not include words that cause physical harm. And freedom of religion should not protect practices that are objectively detrimental to public health.

An additional step, and perhaps a more important one concerning an effective Christian response to future public health crises, is to relinquish any remaining commitment to supernaturalism in favor of a naturalistic Christianity. The notion that physical attendance at religious worship is comparable with the need to shop for food or, worse, that it is a substitute for medical science, is a supernatural claim and central to the problematic argument that religious gathering is “essential” in a time of global pandemic. Unfortunately, even religious communities following advice from public health authorities can often inadvertently provide implicit support for the supernaturalism that is a primary source of the problem by appealing for deliverance from the pandemic through the intervention of an all-powerful deity “out there”. The well-meaning call for “thoughts and prayers” has become hollow for many after hearing this refrain repeatedly ring empty against the epidemic of gun violence in the United States, and it is not helpful for public health in our current situation. A commitment to supernatural religion is at best irrelevant to our current health crisis and at worst, dangerous.

While giving up the appeal to the supernatural will be a step too far for many, times of crisis are moments for reassessment, and our current situation may provide the impetus toward a Christian practice that can be true to its tradition while having a more positive and relevant cultural impact. Far from being a betrayal of Christian tradition as some will claim, a non-supernatural commitment to religion will be truer to the core Christian virtue of love and more appropriate and credible for the valuation and protection of life. Fortunately, there is a strong precedent for non-supernaturalistic religion already established in Christian tradition. Building on the influence of theologian Paul Tillich and Bishop John A. T. Robinson, Bishop John Shelby Spong has long called for a non-supernaturalistic Christianity that understands God not as “a being” but as the Ground of Being, the Source of all Love and Life. It should be noted that, when I refer to naturalism here, I am not equating this with a scientific materialism that is necessarily antithetical to religion. Instead, I refer to a perspective in which the meaning and significance associated with religion can and should only be interpreted through a naturalistic, as opposed to a supernaturalistic, lens. It is a religious naturalism and one in line with Catholic priest Thomas Berry’s view that the scientific story of the universe describes divine manifestation.

It is worth starting a conversation concerning how a naturalistic religious response to COVID—19 can be a catalyst for a more seamless relationship between Christian tradition and public health. Relieved of supernaturalism, the Christian commandment to love one’s neighbor infused with an incarnational understanding of sacramental grace, the view that divine grace is conveyed through material reality and therefore life is imbued with sacred value, has powerful implications. The incarnation does not have to be viewed as a one-time supernatural event in which a transcendent deity enters the single human life of Jesus. Instead, a naturalistic understanding of grace extends an understanding of the incarnation to the entire natural environment and makes the protection of the beautiful mystery of life not only a vital priority but the only valid way to honor God in our contemporary context. An understanding of prayer devoid of petition to a supernatural deity who will unilaterally intervene on our behalf can instead be grounded in orientation toward an awareness that we are inextricably connected in the lives we share. In the midst of a pandemic, this means that what is best for those who are most susceptible to dangerous infection and for emergency, medical, food service, and other essential workers, who are not able to follow stay at home orders, is compatible with the Gospel. A naturalistic Christianity will be good for the future of Christianity, and more importantly, good for public health.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

The number of churches who decided to meet were relatively few, aided by state governments that did not believe in the stay in place of safety policy. The vast majority of churches abided by the rules and used the internet to reach more people than would have been in church as a recent survey using Google analytics has shown.

Even black evangelical noted for their enthusiasm in faith abided by the rules.

Also who today has heard of Paul Tillich outside of the US ultra liberal bubble,much less read him!

The global church is overwhelmingly supernatural in its expression and practice.

The kind of Christianity being rightly criticised in this article appears to me what sociologists of religion would term ‘world-denying faith’. A desire to reject science, ‘this worldly experts’, to reject the value of life in this world, is perhaps part of this impetus. Unfortunately I don’t think it will be effectively countered by the writing of Paul Tillich or the more readable John Shelby Spong. Such liberal theologians are too far apart to be even heard by very conservative Christians. If they have heard of such writers, they are on the ‘dark side’.The problem, being naturalistic, is sociological. Conservative Christians often feel to be on the back foot and they want to rebel against this world. Advice to stay at home, symbolises forces they distrust in a society to which they feel they don’t belong. These problems will not be solved until they are properly identified. I’ve written a bit about this in my Judging Religion A Dialogue for Our Time.

“Non supernaturalistic Christianity” . . . So, I clicked on that and got the John Shelby Spong article, ‘Charting the New Reformation: The Twelve Theses’. By and large, twelve blasphemies. Wasn’t surprised.