Jair Bolsonaro’s determination to exempt churches and their affiliate organisations from social distancing measures during the coronavirus pandemic is in keeping with an administration closely intertwined with evangelical Christian interests. Filipe Domingues explains why this religious base was central to Bolsonaro’s election win and how it continues to influence a range of government policy, including the COVID—19 response.

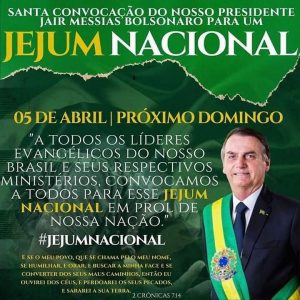

Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro has referred to COVID—19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, as “a little flu”, and has undermined social isolation measures due to their economic impact. He has, however, called for a day of fasting and prayer against the disease: ‘I am asking from those who have faith for a day of fasting, in the name of Brazil, that will rid itself of this evil’, he declared on the radio station Jovem Pan, on Wednesday 2 April. An invitation quickly followed through social media for an initiative on Sunday 5 April named Santa Convocação (Holy Summons). The proposal, the President said, was a counsel of “priests and pastors”.

Bolsonaro’s religious base primarily consists of conservative evangelicals, but he also has the support of some Catholics. On 8 April, the President posted on Twitter images of a meeting with a group from Renovação Carismática Católica (Catholic Charismatic Renewal). They carried the image of Our Lady of Fátima and stated that Bolsonaro is part of God’s “salvation project”. ‘You will liberate us from Communism,’ they told him.

The Bolsonarista project is intrinsically religious. Bolsonaro was elected in 2018 with the support of a prominent group of conservative Christians, over whom he still has influence. Even when a matter is not about religion, the far-right president incorporates elements of religious discourse. This religious base has likewise influenced the way he deals with the current pandemic. Bolsonaro has gone to the courts to keep churches open, considering them “essential services”. He also recommends an almost miraculous remedy against COVID—19, hydroxychloroquine, the effectiveness of which still lacks scientific evidence.

A Conservative Alliance

Jair Bolsonaro came to power without an organised political base. He has no stable relationships in parliament and even broke from the party that elected him, the Social Liberal Party (PSL). He is now attempting to set up his own party, Alliance for Brazil, led by himself and his three sons.

His support network was in fact composed of an alliance between: (a) liberal economic businessmen; (b) agroindustry representatives; (c) a rigorous conservative military wing (Bolsonaro himself was a paratrooper in his youth and blindly defends the dictatorial regime that ruled the country between 1964 and 1985); and (d) conservative religious leaders.

This network harnessed the popular anti-corruption sentiment that led millions of people to take to the streets from 2013, a sentiment that culminated in the federal police’s “Operation Car Wash”, through which politicians and business figures were arrested on corruption charges.

The Carwash Operation elevated judge Sérgio Moro – who imprisoned former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and is currently Bolsonaro’s Justice Minister – to “popular hero” status. Lula was released in November 2019 after 580 days in prison and remains free while his several court cases are ongoing.

Bolsonaro won with a populist discourse. His highly controversial character was no hindrance: he was elected even after countless misogynistic, homophobic, pro-torture, pro-gun and anti-human rights declarations.

The sentiment that helped elect Bolsonaro included “antipetismo”, a hostility to the Worker’s Party (PT) of former presidents Lula and Dilma Rousseff, who suffered an impeachment in 2016 over fiscal responsibility under strong popular and economical pressure. This sentiment railing against a historical public enemy, Communism, was part of the Bolsonaro campaign’s discourse, particularly among his millions of followers on social media.

The role of religion

In the religious field, Datafolha research showed that, amongst evangelicals, the president achieved over double the votes of his opponent from PT, Fernando Haddad, a candidate endorsed by Lula. Among Catholics however it was a close election, with support split 50-50. Bolsonaro attracts more conservative Catholics, whilst Haddad captured those more concerned with social issues.

Evangelicals make up around 22% of the Brazilian population, whilst Catholics are at 65%, according to the 2010 census. Bolsonaro claims he is Catholic, while his wife Michelle is evangelical. However, he appears to be much closer to evangelical leaders. The president called the Catholic Bishops Conference (CNBB) “the rotten side of the Church” and didn’t make a point of visiting Pope Francis. His government even used the national intelligence agency to verify the intention of the Amazon Synod.

President Bolsonaro has been signalling an increase in tax exemptions for churches and organisations connected to powerful media-prominent pastors in the country. An example of this is TV Record, which is owned by Bolsonaro ally bishop Edir Macedo of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God. The federal government’s publicity expenses to TV Record have increased over 60% under Bolsonaro, to the detriment of the biggest broadcasting company in the country, TV Globo.

Another curious element is Bolsonaro’s almost unconditional support of Israel, a country without any tradition of commercial relations with Brazil – whilst Arab nations are big consumers of Brazilian commodities. Bolsonaro considered moving Brazil’s embassy to Jerusalem, copying Donald Trump, and sees prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu as an international ally whom he has called “brother”. Here, the religious note is louder. For many evangelicals, Christian civilization will only peak again when it controls the Holy Land.

The historical religious complexion of Bolsonaro’s government brings up a series of questions, the most obvious of which being the relationship between State and Religion. The president has evangelical ministers, such as Damares Alves of the Human Rights ministry, whose primary experience is being a pastor. Bolsonaro has also stated he intends to nominate a “terribly evangelic” judge for the country’s Supreme Court, when he gets the chance.

This religious vision has also affected the COVID—19 response. As mentioned above, Bolsonaro has gone as far as naming churches as “essential services” that must remain open, even during a prolonged period of social isolation. A judge blocked this move and annulled the validity of the presidential decree, but Bolsonaro’s administration appealed and managed to have churches reopened for a few days. The matter is still not closed, but on 14 April, another judge said ‘religious activities of any kind’ should be excluded from the list.

The pressure to keep churches open comes from, again, the evangelical wing, which also has a strong presence in parliament. Pastor Silas Malafaia, one of Bolsonaro’s key supporters, referred to social isolation as “second-rate quarantine”, and has had posts on different social media platforms deleted on the back of his comments (as has the President.)

On the Catholic side, many bishops hesitated to suspend the celebration of mass, including the Cardinal of São Paulo, Odilo Scherer, and the Cardinal of Rio de Janeiro, Orani Tempesta, before finally accepting the measures following the recommendations of the state governments and the World Health Organization. On the other hand, the president of the episcopal conference, Walmor Oliveira de Azevedo, Archbishop of Belo Horizonte, described the President’s social isolation policies as worrying. Holy Week was celebrated with empty churches across Brazil.

For Bolsonaro, hydroxychloroquine is the medicine to cure COVID—19, despite an absence of conclusive international evidence of its effectiveness and side effects. As Maria Cristina Fernandes, the political columnist for the Valor Econômico newspaper, puts it, “in the midst of an epidemic that has already killed a thousand Brazilians, the president prescribes a miracle potion.”

It is not yet clear to what extent Bolsonaro maintains the public support that elected him. Research over the last few weeks shows a drop in his popularity during the pandemic, although his Health Minister Luiz Henrique Mandetta has been rated highly (which prompted Bolsonaro to sack him).

There isn’t yet a political climate for impeachment, according to the president of the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house of Parliament), Rodrigo Maia, who would be responsible for opening the process. Besides, the idea of Bolsonaro’s vice-president, general Hamilton Mourão, assuming office and opening a new military era doesn’t comfort Brazilians.

The fact remains that Bolsonaro’s religious bias is determining his response to the coronavirus pandemic. And it will certainly define his political future.

Note: This article has been translated into English by Inês Cortesão. For the Portuguese version, click here.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

While I do agree that the majority of evangelicals indeed support Bolsonaro, I think the article makes some generalizations that are not consistent with the plurality (both theological and political) and the decentralization of the evangelical church in Brazil.

Also, evangelical Zionism is much more complex than what is written about it in the text.